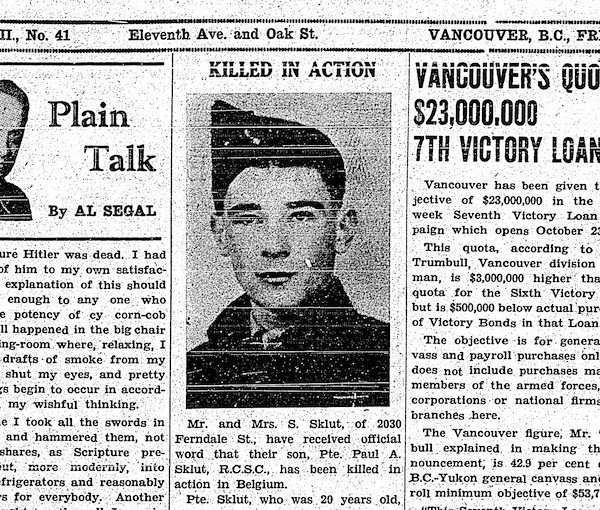

Child survivor Lillian Boraks-Nemetz speaks at the community’s Yom Hashoah Commemoration May 5. (Rhonda Dent Photography)

The pogrom of Oct. 7 and the hurricane of antisemitism that has swirled since then added resonance to commemorations of Yom Hashoah this week.

Around the world, Jewish communities united in different ways to mark the annual Holocaust remembrance day. Sunday night, May 5, the local commemoration at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver featured child survivor Lillian Boraks-Nemetz, who reflected on the unmistakable parallels across time, of “Broken families, broken bodies and minds and the poor frightened children and much more.”

Recently, said Boraks-Nemetz, she heard the words of Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Gilan Erdan, who reflected on how a sunny Shabbat morning in Israel turned, in a matter of seconds, into hell.

“On just such a sunny morning, in Warsaw, I lost my childhood,” said Boraks-Nemetz, who was introduced Sunday night in a touching tribute by her son, Stephen. “The day Nazis invaded Poland, I remember German bombers flying low over my head against an innocent blue sky and as World War Two began on Sept. 1, 1939, I had to become an adult at the age of 6.”

In the war that began that day, she said, 1.5 million Jewish children were murdered. She suffers guilt and questions around her survival when so many, including her little sister, did not live.

“Some of us were younger than others. Some older,” she said. “Nevertheless, we were all traumatized – as our brothers and sisters are today, in Israel, and in a world that won’t learn history and its lessons. We don’t feel safe anymore around our world. Thousands protest against us as they have always done, just looking for a reason to express their hate for Jews.”

Boraks-Nemetz shared parts of her Holocaust history, from the earliest time, when her mother took her to a favourite café only to find a sign declaring Jews were forbidden from entering – signs that then proliferated in parks, recreation areas, theatres, streetcars and elsewhere.

“We were beginning to lose our humanity,” she recalled. “Thousands protested against us with words such as ‘Death to Jews,’ ‘Final Solution’ and more.”

Today, she said, similar words are directed at Jews.

“This is being allowed to flourish unpunished, using our freedom of speech for their purposes,” she said. “But surely there are red lines where free speech ends and hate speech begins that must be punishable by law.”

She recalled seeing the wall around the Warsaw Ghetto being constructed, higher and higher, as she watched.

“I asked my father what this wall means,” said Boraks-Nemetz. “I asked many questions. I was almost 7 years old. This wall, he replied, will eventually enclose a part of Warsaw where we will be forced to live.”

That day came when, through a window, she saw a long car with officers and a bullhorn ordering Jews to enter the ghetto or suffer severe consequences.

“From the day I and my family entered our one room within these close, shabby quarters, I felt as if I had stepped out of sunlight into darkness,” she said. “I felt as if I was being stifled and the feeling of being stifled stayed with me as a memory and a trigger all of my life. The wall meant confinement, exclusion, isolation, fear, hunger and quarantine of a disease called typhus.”

Boraks-Nemetz shared the story of how she was to be smuggled out of the ghetto by her father, who had bribed a non-Jew but, when the day came, she was ill and instead her sister was sent out, never to be seen again.

“The streets were treacherous, with children dying of hunger and disease, poor and starved people peddling what little they had for a few potatoes and stealing what they couldn’t buy,” she said.

While smuggling a child out of the ghetto was a life-threatening act for all involved, so was remaining in the ghetto, she said. Eventually, thanks to an enormous bribe, young Lillian was passed through the gate of the ghetto, where she survived on the outside in the care of her grandmother, who had secured a false identity.

“That day, I felt as if I had lost my family, my home and any degree of safety I had felt,” she recounted. “I became numb and frozen. As a child, I didn’t understand why was I being sent away, alone, into a hostile world. I felt I wasn’t wanted by family or society. That day, I lost my identity as a Jew and a human being, a daughter.”

A forged piece of paper gave her a new, false name, false parents, a false age.

With a small blue suitcase in hand, she walked the short distance from her father, past the bribed guards, who looked the other way, into the care of a waiting stranger who would whisk her to a new, still very hazardous, life outside the ghetto.

“Although it was a very short distance, today I think of it as the longest walk, from impending death to the possibility of life,” she said.

Eventually, she started a new life in Canada, married at 19 and took on the role of a typical Canadian housewife, she said. At 40, she had a crisis, during which she was forced to confront the realities of what she had experienced, a struggle she has addressed ever since, through poetry, sharing her story with students and other means. For her, and for so many others, she said, Oct. 7 brought back from the mists of time the collective consciousness and memory of the past.

“We are still persecuted, blamed, hated,” she said.

Rabbi Carey Brown, associate rabbi at Temple Sholom, spoke earlier in the evening, expressing the need to be careful in drawing parallels between historical events, but acknowledging that the traumas of the past inform reactions to the present.

“It is difficult to distinguish between remembering the past and living in the present,” she said. “It feels inseparable.”

The current generation, said Brown, owes it to the memory of those who perished in the Shoah, as well as to the generations yet to come, “to take seriously and be steadfast in our commitment to ‘Never again.’”

The solemn ceremony began with Holocaust survivors in a procession escorted by King David High School students who are descendants of survivors.

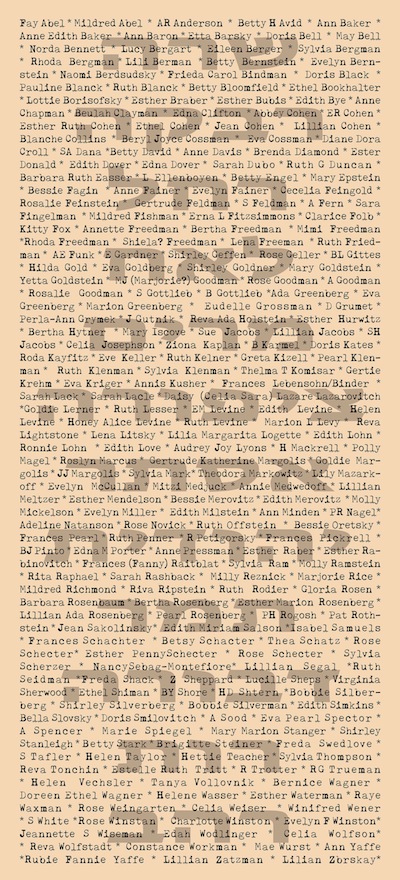

Shoshana Krell-Lewis, a member of the board of directors of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre and a daughter of the centre’s founding president, Dr. Robert Krell, welcomed the audience and acknowledged elected officials and survivors. In recognition of survivors from the former Soviet Union, Irena Gurevich translated into Russian.

Sarah Kirby-Yung, deputy mayor of Vancouver, represented the city.

Cantor Yaacov Orzech recited El Moleh Rachamim.

A moving musical program by artistic producer Wendy Bross Stuart featured Eric Wilson on cello and singers Erin Aberle-Palm, Cantor Shani Cohen, Lisa Osipov Milton, Matthew Mintsis, Kat Palmer and Lorenzo Tesler-Mabe.

The program was presented by the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, funded through the Jewish Federation annual campaign and by the Province of British Columbia, and supported by the Gail Feldman-Heller & Sarah Rozenberg-Warm Memorial Endowment Fund, Temple Sholom Synagogue and the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver.