Little Richard, left, and Jackie Shane. A still from the film Any Other Way: The Jackie Shane Story, which closes the DOXA Documentary Film Festival on May 11. (image from NFB and Banger Films)

An incredible voice, a charismatic performer, a unique human being. Yet, most of us have never heard of Jackie Shane, a rising R&B star in the 1950s and ’60s, who appeared to disappear in 1971.

Michael Mabbott and Lucah Rosenberg-Lee’s feature-length documentary Any Other Way: The Jackie Shane Story closes the DOXA Documentary Film Festival on May 11 at Simon Fraser University’s Djavad Mowafaghian Cinema. In addition to Toronto Jewish community member Rosenberg-Lee, who may attend the festival, Winnipeg Jewish community member Toby Gillies is coming to Vancouver with co-director Natalie Baird for the May 10 screening of their short, Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying, which also takes place at SFU’s Djavad Mowafaghian Cinema.

An R&B legend

A Banger Films and National Film Board of Canada co-production, Any Other Way mixes animation and real-life footage, using Shane’s music, recorded phone conversations between Mabbott and Shane, as well as other interviews, photos and the sole recorded performance of Shane to tell the transgender artist’s story. And it’s a fascinating story, from her leaving her home of Nashville, because of safety concerns, as a queer person, to being a musician in a traveling carnival, to leaving the carnival for Montreal, then leaving Montreal for Toronto, where she immediately felt at home.

By 1963, Shane was a sensation. Her recording of “Any Other Way” was a hit, even though radio stations in Toronto at the time generally did not play Black music – people called CHUM Radio so much they had to play the song and it rose to #2. Shane was invited onto The Ed Sullivan Show but turned them down because they wouldn’t let her perform with makeup, dressed as she wanted; she didn’t do American Bandstand, saying it was a racist show. Shane chose not to do other shows or tour. She recorded her one live album in Toronto.

But not being able to be her true self took its toll and Shane walked away from her success in 1971, changed her name and moved. “I chose Los Angeles because I wanted to feel something else,” she says in the film.

For family reasons, she eventually had to return to Nashville, where she became a recluse, only emerging in 2016 for a reissue of her songs. Nominated for a Grammy in 2018, she was ready to tour, but died in 2019, before that could happen.

Among the treasures found in Shane’s storage unit was an autobiography she had handwritten, as well as unreleased recordings.

“Those discoveries … were incredible,” said Mabbott in an interview on the NFB website. “After Jackie passed away, we started working with her family, who didn’t know that Jackie existed, and then inherited her incredible archive. As they were discovering who Jackie was, we were understanding her through her jewelry and tapes. What was also born out of that is the family’s story, which was a slightly unexpected creative approach.

“Hearing the family talk about her, learn about her legacy and describe what it meant to them was obviously very personal but also really universal. This is a family that lived blocks away from her, didn’t know she was there and missed out on having her. I think that a lot of us feel that loss and that translates in all sorts of ways.”

Happy imaginings

The NFB short film Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying also explores loss. The PR material describes the seven-minute work as a “meditation on love, grief and imagination,” which “celebrates life and the transformative ability of art to elevate and transcend us.”

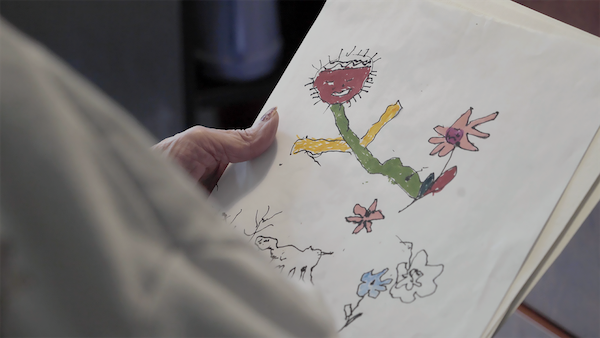

Featuring Edith Almadi, the short uses Almadi’s artwork and words to spur contemplation of the bonds people form, and what it’s like to lose a loved one. In this case, Almadi is recalling her son, who recently died.

“I fly with him,” she says, and she feels happiness. In the animation of Almadi’s artwork, we see her son fly to the moon and beyond, with fairies, butterflies and other creatures. Not only is she with her son in her art, but also with everyone she loves. In her imagination, she is totally free.

“Our initial motivation for interviewing Edith was to save memories for ourselves – we find the way she speaks fascinating and poetic,” write Gillies and Baird in a directors’ statement. “When Edith looks at her drawings, she sees her memories and fantasies. She is able to escape her physical circumstance, through entering her marker and watercolour worlds.”

Gillies and Baird have led an art program at Winnipeg’s Misericordia Health Centre since 2014, and that’s where they met Almadi, a Hungarian immigrant in her late 80s, who uses a wheelchair.

“In our time knowing Edith, she has always loved sharing her outlook publicly,” the directors write. “As we have developed the film, we have shown Edith our progress along the way. She says, ‘That’s me’ and ‘That’s all I have to give’ proudly. Facilitating art-making in this personal care home has allowed us to meaningfully connect with many people in their last stages of life. As directors, this film gives us the opportunity to share this one particular experience of intimacy found through collaborative art-making.”

DOXA runs May 2-12. For tickets and the full festival lineup, visit doxafestival.ca.