As I stepped out my front door for an afternoon walk, I met an older dad taking a walk with a 15-month-old baby girl in a carrier on his chest. She was wiggly. The dad leaned over so the baby could pet my (sizeable) Gordon Setter mix dog. She babbled and waved and touched. She was in on all the action.

While my kids are now 12, I was transported immediately back to the days of naps and screaming tantrum wake-ups. I remembered the power of nature walks and time in a baby wrap, which often calmed both. To this dad, I just looked like an older woman with a big dog, but, by the end of the walk, he had the picture and we’d even figured out that our spouses worked at the same university.

Before this, I’d been concentrating on work, writing an opinion piece about a Winnipeg swimming pool that faces closure and potential demolition. Its name, Happyland, felt poignant and sad. To some, demolishing an aging outdoor facility that serves our winter city for only a couple months a year seems obvious, in terms of its financial worth. Yet, for us, or anyone who has had a chance to play in the shallow end with splashing kids, eager to try out their swimming skills on a sunny day, it’s a hard loss.

These random moments make up the stories of our families, our daily lives, and maybe our bigger communities. They are small and insignificant as they happen, but, at the same time, contain so much. As the dad in his 40s talked to me about being with his partner for 21 years before having a kid, and about “this magnificently overwhelming” experience, I imagined how spectacularly their lives had changed with the birth of this child.

My daily Jewish text study is not always something relatable, but things will pop back into mind at later times. Sometimes, I study my Daf Yomi, my page of Babylonian Talmud a day, and I struggle. Each day, I get an email, an essay, from My Jewish Learning that helps me stay on track and focused on one issue on a page. For Bava Metzia 46, there’s a discussion around how we define acquiring something. Does it happen when we exchange money for the physical object? Does it happen when we “pull,” or physically take, the object? The text goes further into what amounts to an ancient currency exchange counter.

Imagine traveling from Country A to another country, Country B, and you needed some cash. Your money from Country A is no longer good in B. Does it have value? If you exchange it, are you technically buying B’s currency with invalid currency from A? Is the money invalid because it’s no longer in use as your empire disintegrates, or because Country B doesn’t recognize it? Can these currencies, if invalid, still be used privately? (Like cryptocurrency, perhaps?) These are complicated ideas, but the rabbis saw that governments – kingdoms, provinces, countries, etc. – come and go. What is meaningful in one place might be worthless in another.

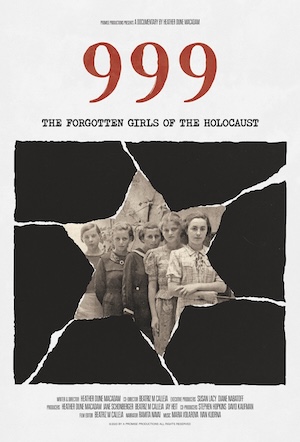

I layered this on top of Bava Metzia 39, a page that just ripped me up as I studied it. It was about who can be in charge and how to manage the assets and property of a captive when they might still be alive, and how to reassess these practical matters if word arrives that the captives have died. The page explored the details: if minor children were involved, and how to supervise a woman’s property when her mother or sister died in captivity. It was heartbreaking to read this text, codified more than 1,500 years ago, with hostages still in Gaza.

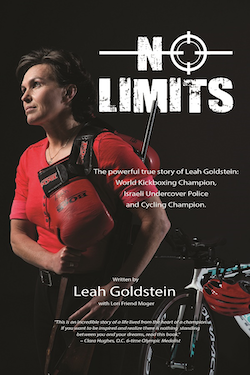

As the date of Israel’s 76th Independence Day approaches, I’m left juggling two concepts. There’s the physical reality of the state – its currency, its government and its infrastructure. Then there’s the enormous emotional, up-and-down response many Jews around the world are experiencing as we struggle as a big extended family through the current war and the antisemitism worldwide. The only thing I can liken the emotions to is that of parenthood. That gut-wrenching, desperate crying from your baby, or the shrieks of joy from your tween as he splashes towards you in a pool. The emotion is overpowering, even while you juggle the practical notions of how governments behave. My parallel universe in Winnipeg: how much municipal money it costs to repair city infrastructure and whether your money (in whatever currency) is enough to pay for ice cream after the swim. The emotional joy of an ice cream after a good splash … that’s something to dream of doing again.

About 35 years ago, I was a teenager living on a kibbutz, splashing in an outdoor swimming pool on a sunny day. When I got out, I might share a slightly melted chocolate bar with my roommate as we changed for dinner. The truth is I have no idea if that kibbutz pool still exists. I haven’t been there since I was 17, but just like Happyland in Winnipeg, it isn’t the concrete that matters, it is those powerful memories of play with my friends.

I’m not sure if it’s possible to sort out all the actual infrastructure costs and damage that Israel, Gaza, the West Bank and Southern Lebanon face. The regional rebuild after this catastrophe will be enormous. The lives of people in the region are irrevocably changed. Meanwhile, if we can avoid numbness and hold onto powerful emotions like the clasping finger of a baby, and the laughter and that cool pool water on a hot day, maybe there’s the potential to regain our equilibrium.

I wish Israel good health on this birthday … good emotional and mental health even if, physically, things are still a hot mess. If Israel were a person? I’d be leaning in for a tearful hug over the cake, saying “You know I love you, right?”

Joanne Seiff has written regularly for the Winnipeg Free Press and various Jewish publications. She is the author of three books, including From the Outside In: Jewish Post Columns 2015-2016, a collection of essays available for digital download or as a paperback from Amazon. Check her out on Instagram @yrnspinner or at joanneseiff.blogspot.com.