The organizer of a conference panel I’m going to be on asked me some questions ahead of the event. He asked how to find hope from a Jewish perspective amid challenging times. I responded with both academic Jewish content and personal information about my sons’ recent big success at a science fair. This person, a male academic, quickly grasped the personal narrative I provided – he thought it was about being a mother. Let’s not be “essentialist,” I suggested. My ability to provide information about hope doesn’t stem from reproduction alone.

If one looks at what is going on in the United States, where there’s interest in limiting women’s reproductive rights, including motivating women to have more children and boost the birth rate, one might think that is what women are mostly for: reproduction. Yet, all sorts of data indicate that, for example, in a country like Israel, which has a high education rate and good possibilities for women, a high birth rate is also possible.

Perhaps choosing to have multiple children is easier with better health care, reliable social networks and support and maternity leave, and in a country that ranks high in terms of happiness on a global scale. Countries without birth control or proper education for women have high birth rates, but there are also high mortality rates. Focusing on women’s reproductive capabilities alone misses the boat. If women are educated and engaged in their country’s workforce, they contribute more than their biological value – the quick response of a male academic to traditional rhetoric about mothering left me disappointed.

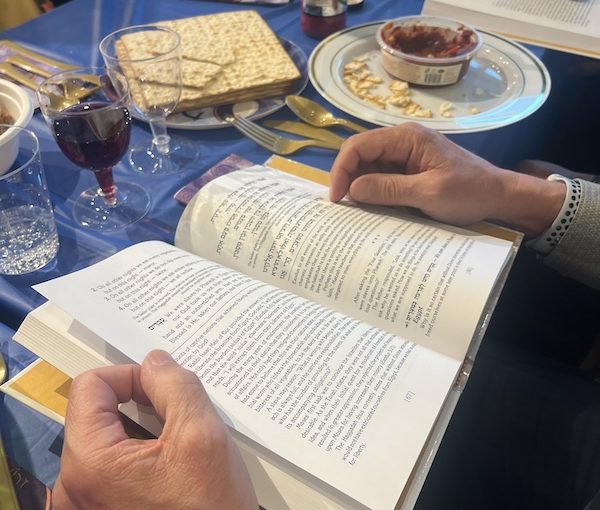

This notion of maintaining hope during challenging political moments can be approached in many ways. I’m still sorting out what I’ll say in the five-minute slot on the conference panel. However, something I learned yesterday in the Babylonian Tractate of Makkot, on page 20b, made me think further about these issues.

Makkot 20b is about haircuts and ritual cutting as a mourning practice. First, Jews are not supposed to cut their hair in certain ways. Second, self-harming through incisions or ritual mutilation isn’t considered an acceptable mourning practice – self-harm isn’t OK.

While I studied this, I was also checking out the Canadian election results. My father, in the United States, was surprised that we hadn’t let our kids stay up late to watch what was happening. I explained that we’d voted early, and that our kids had voted in a school mock election. Also, we wouldn’t know the complete results until later anyway. More importantly, my kids needed sleep to cope with other activities later this week. Sleep felt like more important self-care.

It struck me that much of our tradition, and Jewish law, tries to maintain a complicated form of self-care. Even in dire circumstances, Jewish tradition encourages us to practise resiliency, intellectual curiosity and hope. Each day, the sun will rise, our souls will return and we will have what we need, like clothing and food, and feel grateful for it. As I write this, I hear Omer Adam’s popular musical version of the traditional prayer said on rising, “Modeh Ani.” (Google it, it’s good!)

While we also pray for our country and its leaders, sometimes we jokingly invoke the words that Tevye quotes his rabbi as saying in Fiddler on the Roof: “A blessing for the czar? Of course! May God bless and keep the czar … far away from us!”

My household felt strangely conflicted about voting. We knew for instance that the Conservatives, in the past, cut funding for research and science, which worries us. Choosing parties that maintain or grow science funding is important to us personally, since my husband is a science professor. His lab needs funding to do research. Good science research can protect us. However, the Liberals have a poor track record of protecting Jewish Canadian citizens. Our local NDP MP has expressed something akin to real hate in my dealings with her. So, again, we can think like Tevye’s rabbi: we bless the outcome of a democratic election – no matter how it goes – while hoping those in charge don’t get close enough, through their actions, to do us any harm.

Similarly, the rabbis acknowledged that mourning causes us great psychological pain. This might encourage some to self-harm. Ideally, we should control that impulse. Self-care is a balancing act. It’s not always clear how to make safe choices.

Locally, I watched politicians’ interactions with the Jewish community with interest. In one case, an incumbent Jewish Liberal MP of a riding known to historically have a “big” Jewish community mentioned that perhaps only 5% of his riding was Jewish. His efforts made to support the Jewish community and offer allyship to Israel were an expression of his conscience. That choice likely didn’t help his chances and maybe even was an impediment to his campaign, but that decision to act conscientiously offered me hope, too, even if I couldn’t vote for him because I don’t live in his riding.

Sometimes, our choices aren’t as clear as we’d like them to be. It can be hard some mornings to rise full of hope and gratitude amid the political chaos and death we hear about each day. Given that, we need the reminder of ancient, traditional Jewish prayer and thought, too. There are days when I feel praying is a rote practice. Other days, I remember that we’re doing this in a way that brings us connection with ancestors who maybe didn’t have enough food, who suffered with terrible plagues or physical danger. In many ways, things are so much better for us than they used to be. This alone is worth our gratitude.

When the rabbis warned long ago against cutting oneself, they lived in a world without antibiotics or effective medical care. My conversation about finding Jewish hope wasn’t simply about reproduction, my maternal pride, but rather my pride in the kids doing good science. I have hope because I don’t only believe in blind faith, I also believe in science. Whether it’s Israel’s Iron Dome, Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine, or other discoveries, doing science is another form of self-preservation.

The world can be a painful place. We must make compromises to continue as a small minority ethno-religion. Those choices require us to acknowledge what’s happening, to make nuanced decisions based on what’s best in the moment, and to build a better world each day.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m proud of my children, whatever they do, but I’m filled with hope because my Jewish kids won all sorts of accolades at a divisional science fair. To me, that’s Jewish self-care for the future. Yes, it’s also a political statement, too.

Joanne Seiff has written regularly for the Winnipeg Free Press and various Jewish publications. She is the author of three books, including From the Outside In: Jewish Post Columns 2015-2016, a collection of essays available for digital download or as a paperback from Amazon. Check her out on Instagram @yrnspinner or at joanneseiff.blogspot.com.