Upstanders Canada held a nationwide webinar last month to introduce a toolkit aimed at confronting antisemitism in the various forms it may manifest – particularly in the inherent biases people may not be aware they carry.

At the June 23 launch, Pat Johnson, the founder of Upstanders Canada, discussed the toolkit, called Be An Upstander: How Allies Can Recognize and Contest Antisemitism. Among those attending the online event were representatives of several faith-based organizations. Most attendees were not part of the Jewish community.

Johnson outlined how antisemitism works and the characteristics contained within antisemitism, such as “othering” (casting a group of people as different from the rest of society), victim-blaming, and inverting the victim and the perpetrator.

The toolkit demonstrates how these characteristics of antisemitism can lead to projection – where a society places the blame for things it fears, hates or does not understand onto Jews. This can lead to conspiracy theories in which complex world problems are simplified into a clearcut package that frequently places the blame on Jews.

Antisemitism is a foundation of many conspiracy theories in that the theories usually rest on the belief that a powerful group of Jews controls events. The theories do not need to specify Jews as the people behind what is considered wrong, but rather can use references to “Hollywood,” “cosmopolitan elites” or “globalists,” which equally fulfil the purpose of implying that Jews are doing nefarious, self-serving deeds behind the scenes.

Feelings of envy and inferiority, the toolkit points out, may distinguish antisemitism from other forms of racism. Whereas many types of prejudice come from a sense of superiority, antisemitism is derived in part from the belief that Jews “think they are better than everyone else.” This, in turn, leads to “punching up,” or, as Johnson says, “the idea that attacking a perceived ‘superior’ is a way to advance social justice, though the person being punched is always a victim.”

Johnson offered a picture of what antisemitism may look like when it is not obvious.

“Blatant antisemitism is easy to recognize,” he said. “It is also the form of antisemitism most likely to turn violent and is, therefore, the most dangerous. But all people of goodwill recognize and condemn that form of antisemitism. More subtle, unconscious forms of antisemitism exist in inherent biases, stereotypes and tropes that people may carry without even recognizing them.”

The stereotype of affluent, high-ranking or privileged Jews, for example, brings with it a specific danger, one that may not be violent but is nonetheless harmful. Antisemitism, Johnson explained, becomes the “perfect prejudice” because the concept of powerful Jews renders the notion of taking antisemitism seriously invalid as their supposed power makes them immune to discrimination.

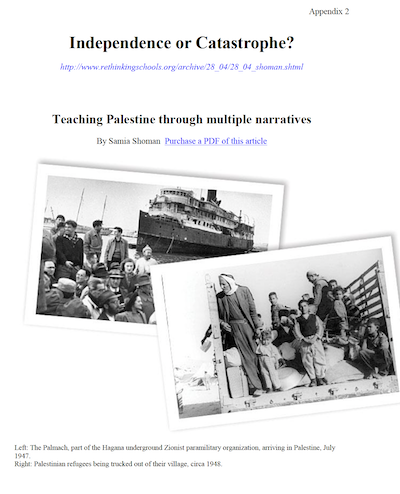

The toolkit touches upon some historical tropes about Jews, such as an alleged “persecution complex” and Jewish “untrustworthiness and disloyalty” in business settings, citizenship and elsewhere. It also discusses blood libels, the Holocaust and blaming the killing of Jesus on Jews.

Regarding equating anti-Zionism with antisemitism, Johnson notes that Zionism is the manifestation of Jewish self-determination in a state and that “anti-Zionism is not criticism of Israel, it is opposition to the existence of the state of Israel.” He discounts the idea that pre-existing biases against Jews have no impact on opinions about the Jewish state and admonishes those who accuse Israel of using historical discrimination for political advantage. The toolkit references the three Ds developed by Israeli politician and human rights activist Natan Sharansky to determine if anti-Zionism is antisemitism: demonization, double standards and delegitimization.

The toolkit adds, “Zionism does not preclude Palestinian self-determination. Coexistence is the only path to peace and it is the responsibility primarily of the people who live there. The responsibility of overseas observers should be to encourage that coexistence – not to exacerbate the conflict by stoking intolerance, here or abroad.”

The toolkit adds, “Zionism does not preclude Palestinian self-determination. Coexistence is the only path to peace and it is the responsibility primarily of the people who live there. The responsibility of overseas observers should be to encourage that coexistence – not to exacerbate the conflict by stoking intolerance, here or abroad.”

One of the problems well-intentioned individuals have when contesting antisemitism is not feeling adequately prepared to respond. For this, the toolkit not only provides many strategies for preparing, but offers encouragement and empowerment.

Be An Upstander, a 20-page pdf document available online, comes with numerous links that allow readers to explore in greater depth subjects surrounding antisemitism and ways of responding appropriately to it.

In addition to Johnson speaking about the toolkit, the launch event featured short speeches from Deborah Lyons, Canada’s special envoy on antisemitism; Zara Nybo, a campus media fellow for HonestReporting Canada and Allied Voices for Israel at the University of British Columbia; and Rabbi Lynn Greenhough of Kolot Mayim Reform Temple in Victoria, which hosted the event. Television personality Shai DeLuca emceed from Toronto.

The Upstanders toolkit was created in partnership with Kolot Mayim, with financial support from the Union for Reform Judaism, the Anti-Defamation League and the Jewish Federation of Victoria and Vancouver Island.

Upstanders is a movement of mainly non-Jewish people standing up against antisemitism. It is a nonpartisan, non-denominational organization, open to Canadians across all differences of identity, orientation, outlook and ability. To find out more and to view the toolkit, visit upstanderscanada.com.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.