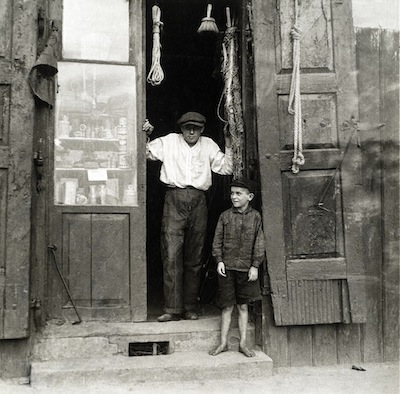

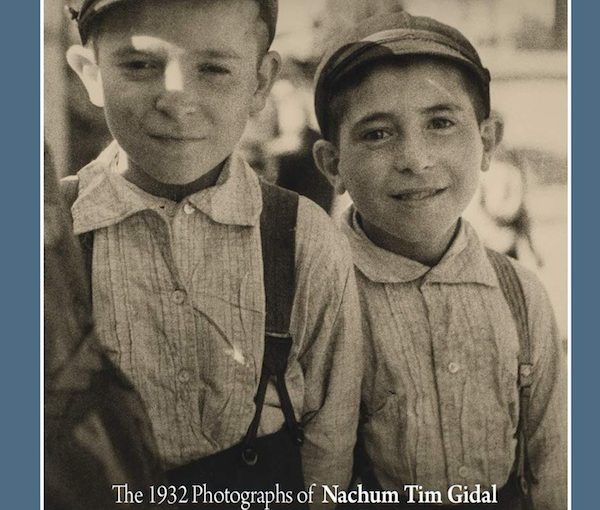

Photographer Jason Langer’s perception of Germany and its capital, Berlin, is a complicated one, and his current exhibition at the Zack Gallery, Berlin: A Jewish Ode to the Metropolis, reflects those complexities. Organized in partnership with the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival, the exhibit is Langer’s first show in Canada.

Langer’s newly published book, Berlin, includes 135 black and white photographs. A selection of these images forms the exhibit at the Zack, which has an emotional sophistication of its own, even though the show is being promoted as a prologue for the book festival. Both the show and the book catalogue the artist’s several trips to Berlin and his explorations of the city. They also provide visually compelling commentary on Langer’s contradictory and evolving feelings for Germany.

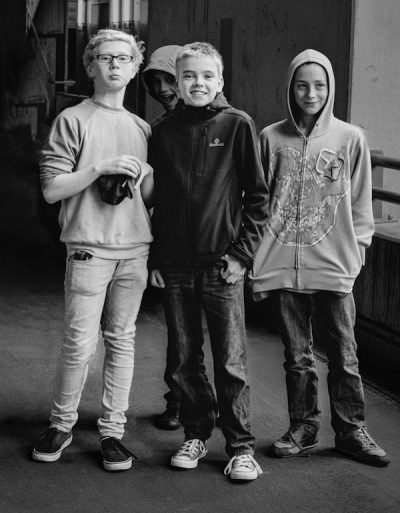

As in life, the then-and-now overlap and, occasionally, the juxtaposition of the past and the present are jarring in Langer’s imagery. On the one hand, Germany is the country where the Holocaust originated, the country that erased its Jewish population almost entirely and spearheaded the destruction of the Jews of Europe. On the other hand, it is a modern country of laughing kids, hardworking people and beautiful architecture, a country that acknowledges its past actions and tries to make amends to the Jews. It is a country inspiring fear, hatred, respect and admiration in varying measures.

Langer writes in an essay about his relationship with Germany and its progression from total negativity to growing understanding. When he was 6 years old, his family moved from his native United States to Israel, where he spent his formative years, until age 11, on a kibbutz.

“Every year, each children’s house would visit the Holocaust memorial, located on the kibbutz property, during Yom Kippur…. We were asked to walk silently and led into a courtyard with one building and three short walls,” writes Langer. “I remember the walls were made of large, rectangular stones, grey in colour and a bit rough and oddly shaped. We learned about how the Jews had suffered, first as slaves in Egypt and then in the Holocaust by the Germans.”

Later, as an adult, he “vaguely remembered having heard fearful stories of German people from my mother and grandmother, though my mother also made jokes about Germans, putting on a comic fake accent. She died in 2003 and I inherited her books, among other things, including a kind of illustrated encyclopedia titled The Wonderful Story of the Jews, written by Jacob Gewirtz. It was published [in 1970], not long before our move to Israel. The text refers to the Germans’ ‘unspeakable crimes’ against the Jews, as well as the ‘unending ravages of war, persecution and tyranny’ they had faced. Some of the illustrations are quite scary, showing buildings on fire and Jewish people menaced by gun-wielding Nazis. The book presents Israel as a place of refuge, the kibbutzim as almost unique.”

After being exposed to such ideas during childhood, Langer’s predominant feeling towards Germany was aversion. But then, in 2008, when he was already an established photographer, one of his friends suggested he photograph Berlin.

“He thought the city would be a good match for my sensibilities but I met his suggestion with trepidation and fear,” Langer recalled. “I harboured many preconceived ideas about Germans and Germany. I imagined Berlin as a vast, cold, unfriendly, gritty place, but, at the same time, it seemed exciting and sexy somehow.

“I decided to see Berlin for myself, keen to challenge my existing ideas and also uncover reminders of the Jewish people who had lived there, until they fled or were hunted down and killed by the Nazis.”

In the next five years, Langer visited Berlin frequently. “From 2009 to 2013,” he said, “I made five trips for two weeks at a time. I stayed in a flat with about six people. When they were going on vacation, they would let me know, and I would fly over and occupy their rooms. They would also give me advice on where to go.”

During those visits, he took multiple photographs and strived to form a new narrative regarding his feelings and associations regarding Germany and its people.

“This work is an attempt to remember, confront and unwind my attitudes about Germans, Germany, Berlin and my Jewish inheritance; these images are part discovery, part remembrance and part fantasy,” he explained. “They’re my attempt to stand where Jewish people were rounded up and deported, to remember but also reassess. They’re an effort to confront my internal attitudes and prejudices, to look into people’s eyes and find a continuation of kindness, to be open to the happiness of contemporary life in Berlin.”

Some photographs in the gallery are full of anguish and terrible beauty, like the Holocaust Memorial, consisting of 2711 concrete slabs (stelae) of different heights, or an ornate door of the Stiftung Neue Synagogue, built in 1865, the only synagogue in Berlin to survive the war, though its interior was burnt.

The horror of the war is also reflected in the image of an old, dilapidated shed, the “goat house,” where one Jewish family, a mother and a daughter, hid for several years to survive the Nazis’ attempt to exterminate Jews. No water, no heat, no electricity, just the women’s indomitable spirits and relentless wish to live.

Every photo has a story to tell. Many a story of heroism and tragedy. But there are other pictures, too, reflecting modern Berlin, the city of now. Laughing boys, a tired-looking woman, an anti-fascist demonstration, various streets and buildings.

Langer writes: “It was a strange mix of death and life.… There was a sense of youth, freedom and joy I felt in Berlin.… Whenever I wandered, I took it as a gift of prolonged, uninterrupted time for reflection.”

The artist’s wanderings and reflections led to the creation of the photobook Berlin.

“This book is not a document,” said Langer. “It is a dream within a dream within another dream. Berlin is immense, there was no way I could cast a wide enough net to what it’s like. Instead, I have painted a picture of then and now, pain and pleasure, some people who died long ago and those who are living and young, all from my own perspective.”

Berlin: A Jewish Ode to the Metropolis opened on Jan. 6 and will continue at the Zack Gallery until Feb. 16. For more information, visit jasonlanger.com.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].