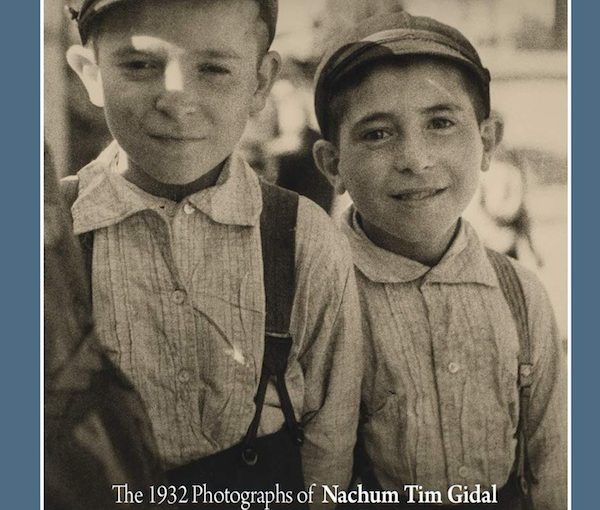

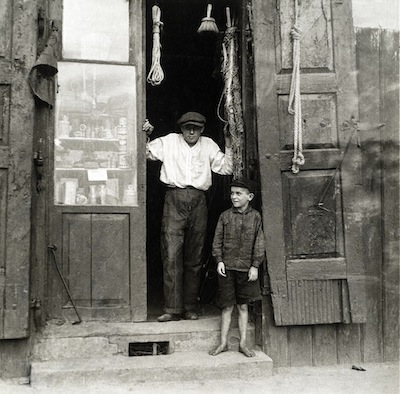

This photo, called “Generations,” was taken by Tim Gidal in Tel Aviv in 1935. (courtesy Zack Gallery)

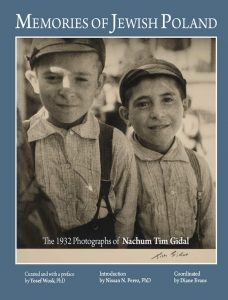

The current show at the Sidney and Gertrude Zack Gallery, Invisible Curtain: The 1932 Polish Photographs of Nachum Tim Gidal, was organized in partnership with the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival, which runs Feb. 20-25. Gidal (better known as Tim Gidal or Tim N. Gidal) was a renown photojournalist of the last century and the exhibit’s images come from the new book Memories of Jewish Poland: The 1932 Photographs of Nachum Tim Gidal. (For a review, click here.)

The driving force behind the book’s publication was Yosef Wosk, who wrote its preface. Wosk approached Zack Gallery director Hope Forstenzer and Jewish Book Festival director Dana Camil Hewitt about a year ago, Forstenzer told the Independent. “He suggested we have a Tim Gidal show at the gallery to coincide with the festival and his newly published book,” she said.

Both Wosk and Forstenzer curated the exhibit. “Together, we chose about 50 images for the show, as many as the gallery could fit. It couldn’t include all the images in the book, of course,” said Forstenzer.

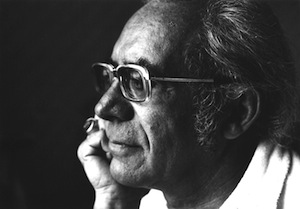

The history of the photographs is best described by the photographer himself in the book’s introduction. In 1932, Gidal, then 23, traveled with two friends to Poland from his hometown of Munich, Germany. It was his first trip abroad. “My knowledge of the political, economic and social conditions of the Jews in Poland didn’t seem to square with my feelings about their spiritual life,” he wrote. “So I decided to go and see for myself.”

Gidal, who passed away in 1996, took numerous photographs of people and places, as he went from shtetl to shtetl on his three-week “little odyssey.” He wrote: “I encountered spiritual and material heights and depths: material well-being and abject poverty, rejuvenation and dissolution. Some were rich, but many more were very poor. It was a hopeless poverty, endured with an incredible humility. I met men of faith and hypocrites … atheists, socialists and communists, Zionists and Bundists, Orthodox and assimilationists. We also experienced the all-pervading Jewish humor.”

Everything the young photographer experienced was reflected in his images, including those now on display at the Zack. We see children laughing and women looking far older than their real years. We see ancient eyes and tired, worn hands. We see educated men reading in front of a synagogue, and broken windows and peeling walls the next street over. And we know something Gidal didn’t know at the time, which makes this book and the show all the more poignant: not many years later, most of these people would be murdered in the Holocaust, and they and their entire way of life would be lost. But, in Gidal’s photos, his subjects remain alive. According to Wosk, “Each photograph is a monument, a letter in light.”

Gidal’s 1932 Polish photo essay comprises only a small portion of the master’s body of work. His photography journey spanned almost seven decades and encompassed most major players and momentous events of the 20th century.

One of the pioneers in the field of modern photography, Gidal made his debut in 1929 with his first published photo report. He was a proponent of the style of the “picture story” and he captured most of his subjects unaware, instead of staging elaborate scenes. Very few of his subjects posed for his photos, and every image tells a story.

Four years after his trip to Poland, Gidal moved to Palestine. During the Second World War, he served as a staff reporter for a British army magazine. A wanderer and a chronicler of life, he traveled a lot and lived in the United States for awhile. He taught and illustrated books. He exhibited widely.

A portion of the Zack exhibition is dedicated to Gidal’s artistic photography after 1932. The pictures demonstrate his technical progress, as well as his breadth of interests and subjects. There is a lyrical photo, “Generations,” taken in Tel Aviv in 1935 and another – a dramatic portrait of the youngest survivors of Buchenwald, taken in 1945 upon their arrival in Palestine. There is a photo of Mahatma Gandhi at the All-India Congress in Bombay in 1940 and the fascinating picture called “Handshake,” taken in Florence in 1934, which shows two men shaking hands in front of a wall covered with multiple posters of Mussolini.

Half a century before Photoshop was invented, Gidal experimented with his images, compiling them in different combinations and creating something unique, like his triptych of Winston Churchill of 1948 or the Rhomboid photomontage of 1975.

As a photo reporter, Gidal used his camera to record the 20th century in all its glorious and painful contradictions, and his early 1932 Polish photographs serve as a symbol of his multifaceted canon.

Invisible Curtain opened on Jan. 5 and the exhibit will continue until Feb. 25. To see the show’s digital equivalent, visit online.flippingbook.com/view/891736. To book an appointment to see it at the gallery, email Forstenzer at [email protected]. To attend the virtual book launch on Feb. 11, 7 p.m., and to see the full book festival lineup, visit jccgv.com/jewish-book-festival.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].