Left to right: Mia Givon, Lorenzo Tesler-Mabe, Kat Palmer and Erin Aberle-Palm. (screenshot from Kat Palmer)

Holocaust survivors and their descendants were joined by top elected officials and Jewish community leaders in a series of commemorations marking Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, across Canada last week.

In Vancouver, community members gathered together at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver April 27, while scores more watched remotely as the traditional in-person ceremony returned for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic.

Marcus Brandt, vice-president of the presenting organization, the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, welcomed guests and invited Holocaust survivors to light Yahrzeit candles.

“On Yom Hashoah, we join as a community to remember the six million Jews who perished in the Holocaust at the hands of Nazi Germany and its co-conspirators between 1933 and 1945,” he said. “It is also a day to pay tribute to the Jewish resistance that took place during the Holocaust.”

This year marks the 79th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which is the most notable of many acts of Jewish resistance to Nazism.

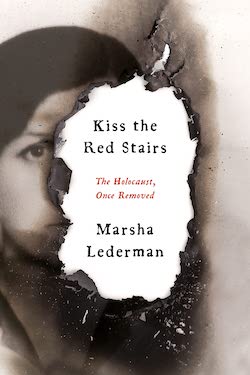

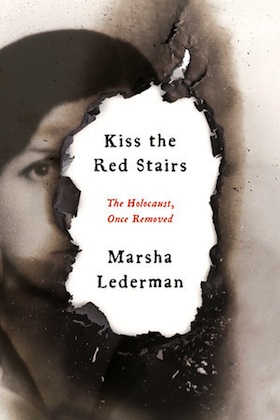

Marsha Lederman, a journalist who is the daughter of two Holocaust survivors, spoke of the importance of telling our stories.

“When I was growing up,” she said, “the Holocaust was everywhere and nowhere. As far back as I can remember, there were hints and references. My parents talked about things happening in camp. What was this camp? I knew it wasn’t like the summer camp that I went to. I knew a lot of their friends were also at these camps, but I didn’t know the details.”

At the age of 5, Marsha met a new friend whose home was filled with laughter and extended family.

“One day, when I came home from a visit at my friend’s house, I asked my mother what was really a simple, innocent question,” said Lederman. “She has grandparents, why don’t I? My poor mother. She was caught off guard and her answer was truly horrifying – at least as I remember it, because I know memory is very faulty. But, as I recall, she said I didn’t have grandparents because the Germans hated Jews and they killed them by making them take gas showers.”

This response raised more questions than answers for the young girl, not least of which was: “What did we do to make the Germans hate us so much and do they still hate us? It was a horrible introduction to the details of the tragedy of my family and it taught me another terrible lesson: be careful about asking questions because the answers could be murder.”

As a result, much of Lederman’s Holocaust education was gained “through osmosis, rather than sitting down and asking questions,” she said.

Her father died when Lederman was a young woman and, in a tragic turn of events, her mother died just as Lederman had bought a ticket to visit her in Florida, armed with a recorder to finally ask the questions she had hesitated to broach in earlier years.

“It’s taken me years to try to figure out what I could have learned in an afternoon at my mother’s kitchen table,” she said. “I have no way of knowing these things because I didn’t ask. We need to ask and we need to tell.”

Lederman explores these questions in a book being released this month, titled Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed.

Amalia Boe-Fishman (née van Kreveld) was the featured survivor speaker at the Vancouver event. Born in the Netherlands, she was less than a year old when the Germans invaded her country. Her grandparents were soon transported to Auschwitz and murdered.

In what is an extremely rare phenomenon, Amalia, her parents and her brother all survived the war years because a Dutch Christian resistance fighter, Jan Spiekhout, and his family hid members of the de Leeuw family in a variety of hiding places over the course of years. Amalia’s mother even gave birth to another child in 1944. (That child, as well as Boe-Fishman’s oldest son, are both named Jan in honour of their rescuer.) Their survival was a statistical miracle. The Netherlands had among the lowest Jewish survival rate of any country during the Holocaust. Of 140,000 Dutch Jews in 1939, only 38,000 were alive in 1945.

Boe-Fishman recalled the day Canadian forces liberated the Netherlands – it was one of the only times in three years that she had set foot outdoors.

“It was strange and frightening outside and close to so many strangers,” she said. “The Canadian soldiers came rolling in on their tanks, handing out chocolates, everyone smiling, dancing, waving Dutch flags. Then I was told I could go home to my real family. But who were these strangers? I did not want to leave the family Spiekhout. They were my family. After all, I had not seen my real family for three years.”

In 1961, she traveled to Israel to meet members of her family who had made aliyah before the war and to reconnect with her Jewish identity. There, on the kibbutz she was staying, she met a Canadian, whom she married and they subsequently moved to Vancouver and had three children.

In 2009, Boe-Fishman and her three sons traveled to The Hague for the investiture of Jan Spiekhout and his late parents, Durk and Froukje Spiekhout, as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem.

“To be together with my children, my brother, and the grown children of the Spiekhout family, this was such a moving event in our lives,” she said.

As part of the Vancouver ceremony, Councilor Sarah Kirby-Yung read a proclamation from the City of Vancouver. Cantor Yaakov Orzech chanted El Moleh Rachamim. Lorenzo Tesler-Mabe, Mia Givon and Kat Palmer, members of the third generation, as well as Erin Aberle-Palm, sang and read poetry, accompanied by Vancouver Symphony Orchestra violinist Andrew James Brown and pianist Wendy Bross Stuart, who was also music director of the program.

The following day, a hybrid in-person and virtual event was held at the British Columbia legislature, featuring Premier John Horgan.

“On Yom Hashoah, we are challenged to ensure the words ‘never again’ are supported by action,” he said. “Over the past few years, there has been an increase in antisemitism in B.C., and the Jewish community is one of the most frequently targeted groups in police-reported hate crimes. That’s why our government will continue working to address racism and discrimination in all its forms.… Today, as we remember and honour those who were lost and those who survived, we must recommit to building a more just and inclusive province, where everyone is safe and the horrors of the past are never repeated.”

Michael Lee, member of the legislature for Vancouver-Langara, spoke on behalf of the B.C. Liberal caucus.

“Every year, we commemorate this day and remember the heroes and the Righteous Among Nations who stood up to oppose the most vile, hateful oppression,” Lee said. “We recognize the victims and survivors of the Holocaust, we make a solemn promise to never forget and never again allow such horrific actions to take place. This is a responsibility that we all must carry with us not only today but every day. It is a responsibility we must be better at upholding, as soldiers at this very moment commit war crimes once again in Europe. We have not done enough. Right here in Canada, we see another year of record rises in antisemitism. We have to do better.”

Lee called on the province to adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance Working Definition of Antisemitism.

MLA Adam Olsen represented the Green party.

“While time distances us from the horrific events, the memories and the stories remain steadfast in our mind and are carried and passed from one generation to the next,” said Olsen. “The Holocaust was an ultimate form of evil, persecution, oppression, genocide, complete disregard for human life, pushed to the most appalling degree…. The Holocaust is a stark reminder of the darkness, the wickedness, that can exist among us. However, it is also important to acknowledge that this is a story of strength, resilience and humanity and, to that, I raise my hands to all of the survivors, the Jewish community, that have ensured that the world knows and hears the stories. As difficult as it is to continue sharing them, we cannot stop hearing them or else we will fall victim to thinking that we have passed that now.”

Rabbi Harry Brechner of Congregation Emanu-El lamented the deaths of Holocaust survivors in the current war in Ukraine, “who died when they were cold, again, and hungry, again, and who died in the face of violence.”

“That never should happen and we all know that,” the rabbi said. “I don’t know how to make those big changes. I’m not a world leader. I’m the leader of a small congregation. But I think we are all leaders of our hearts and if each of us can make that difference, it’s got to have a huge ripple effect.”

Holocaust survivor Leo Vogel said that history records the end of the Holocaust in 1945. “But, for the people who lived through it and survived that horrible blight of human history, for them, 1945 is not when the Holocaust ended,” he said. “It continues to this very day to live in memories and nightmares and ongoing health problems.… The fascist attempt to eradicate the Jewish people must never be forgotten. The memory of the tortured and murdered cannot be shoveled underground as the Nazis did with the ashes. As children in the Holocaust, we were the youngest and, now, in our older years, we are at the tail end of those who can still bear witness.”

Vogel spoke of the unfathomable choice his parents made to hand him over, as a child, to a Christian family for hiding.

“Not long after that deeply painful decision to separate me from them, they were deported to Auschwitz and there they were murdered without ever knowing whether their desperate act to allow me to go into hiding saved my life,” he said. “I get cold chills when I think of the intense agony they went through in making their decision. It would have been their hope, I’m sure, that one day we would once again get together. That day never happened. Their pain must have been overwhelming. Many times, I have wondered what they said to each other and to me the night before they gave me away and, countless times, I have asked myself whether I would have had the strength to do an equal act when my children were young.”

In Ottawa, earlier on April 27, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau touted his government’s steps in fighting antisemitism, including the creation of a special envoy on preserving Holocaust remembrance and combating antisemitism, currently held by Irwin Cotler, and proposed legislation to make denying or diminishing the Holocaust a criminal offence.

“Earlier this year, our country and people around the world were shocked and dismayed to see Nazi imagery displayed in our nation’s capital,” the prime minister said, referring to trucker protests in Ottawa. “For the Jewish community, and for all communities, those images were deeply disturbing. Sadly, this wasn’t a standalone instance. Jewish people are encountering threats and violence more and more both online and in person. This troubling resurgence of antisemitism cannot and will not be ignored. The atrocities of the Holocaust cannot be buried in history.… We must make sure that ‘never again’ truly means never again.”

Shimon Koffler Fogel, chief executive officer of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, picked up on that theme, noting that the term “never again” was “born out of the Jewish experience but was always intended to be universal in its application.”

“How can we witness the atrocities visited on the Rohingya, the Uighurs or the Yazidi and claim the cry of ‘never again’ has meaning?” he asked. “How can we observe the unvarnished aggression against Ukraine and assert we have taken the lessons of the Holocaust to heart?”

He said he derives hope from the fact that Canada seems to have learned the lesson of the MS St. Louis, the ship filled with Jewish refugees that was turned away from Canada and other safe havens in 1939. Now, Canada is a place, he said, “where fleeing Syrian and Iraqi refugees can rebuild their lives, where Afghani women and girls can fulfil their dreams, where displaced, wartorn Ukrainians can find safe harbour.”

“I take great pride that Canada is so committed to Holocaust remembrance and education,” said Michael Levitt, president and chief executive officer of the Friends of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, “A major reason is because of the survivors who, after suffering unthinkable adversity in Europe, rebuilt their shattered lives here, in our great country. Their strength, resilience and willingness to share their deeply personal and harrowing stories have been a gift and a source of inspiration to all Canadians.”

Dr. Agnes Klein, a Holocaust survivor, spoke of her family’s wartime experiences. Israel’s ambassador to Canada, Ronen Hoffman, commended Canada on adopting the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s Working Definition of Antisemitism.

A day earlier, at another virtual commemoration from the Montreal Holocaust Museum, Holocaust survivor Max Smart told of his family’s harrowing Holocaust experiences.

Paul Hirschson, consul general of Israel in Montreal, compared the loss of Jewish life, with its incalculable loss of talent, in the Holocaust with the explosion of Jewish talent taking place in this century.

“Jewish talent lost was one of history’s greatest tragedies,” said the diplomat. “The talent emerging is perhaps the most exciting story of the 21st century…. Antisemitism is still widespread, also here in Canada. Montreal, where many survivors found a home, is no exception. We will defeat hate every time. Hatred will never again rob the world of Jewish talent.”

True to its title, the memoir is infused with recipes, from the hearty Eastern European fare of Margot’s childhood to more adventurous coastal BC cuisine. The narrative follows 23-year-old Margot when she left Winnipeg and her volatile Slavic-Jewish family for the wilds of British Columbia and fell in love with a sea urchin diver. Determined not to repeat the same mistakes as she had witnessed during her parents’ marriage, Margot paints a portrait of a modern-day fishwife left behind to keep the home fires burning.

True to its title, the memoir is infused with recipes, from the hearty Eastern European fare of Margot’s childhood to more adventurous coastal BC cuisine. The narrative follows 23-year-old Margot when she left Winnipeg and her volatile Slavic-Jewish family for the wilds of British Columbia and fell in love with a sea urchin diver. Determined not to repeat the same mistakes as she had witnessed during her parents’ marriage, Margot paints a portrait of a modern-day fishwife left behind to keep the home fires burning.