Aren X. Tulchinsky is Vancouver Public Library’s new writer in residence. (photo by Jeff Vinnick / VPL)

As this year’s writer in residence at the Vancouver Public Library (VPL), Aren X. Tulchinsky proudly represents his two cherished identities as a transgender man and as a Jewish person.

“I bring all of my lived experience into the residency,” said Tulchinsky in a Jewish Independent interview. “I am out and proud as a member of the Jewish community and the LGBTQ2S+ community, and I bring my identities with me into the residency. I guess you could say this is a very Jewish and queer residency. The library has been very supportive of me.”

Tulchinsky wears his heart on his sleeve or, at least his right bicep, which is ringed with a tattooed chai in Hebrew letters. “We celebrated the launch of my residency with an evening of words and music, during which I read from new and previous work, and was accompanied by local klezmer musicians,” he noted.

The 65-year-old Toronto native is probably best known for the award-winning 2003 novel The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky, under his former name, Karen X. Tulchinsky, which evokes the 1933 antisemitic riot at Toronto’s Christie Pits park. He has had a varied career in film and television writing, editing and directing, and penning short and long fiction, including lesbian romance, notably the novel Love Ruins Everything.

Tulchinsky came out as lesbian as a teenager, and has been writing stories since.

Tulchinsky was named in September to the VPL post, which was launched in 2005 to promote Canadian literature. Among past resident writers are Miriam Libicki (jewishindependent.ca/drawing-on-identity-judaism), Sam Wiebe, Rawi Hage and Gary Geddes. Last year’s appointee was Black Canadian writer Harrison Mooney, author of the critically applauded Invisible Boy: A Memoir of Self-Discovery.

Tulchinsky, who lives in Vancouver, responded to the VPL’s call for applications and was shortlisted. “Then I was called in for an interview with about 10 people from the programs and learning department at the VPL central branch,” he said.

“It was a bit intimidating to be interviewed by a whole group of people, but I must have impressed them because, a few days later, the manager of the department phoned to let me know that they had chosen me for the position.”

Asked if he thought his being transgender was a factor in his selection, Tulchinsky replied: “Not really. The only way my identity as a transman was significant is that in the posting the VPL was encouraging writers from under-represented groups to apply.

“Judging from most of their past writers-in-residence, I assumed they would give the position to a more mainstream writer, so I have never applied in the past. Their encouragement for writers from diverse backgrounds … is what motivated me to apply.”

One of his chief responsibilities is acting as a mentor to emerging writers, in particular, those from marginal communities.

“It is my mission to encourage writers from marginalized communities, specifically, BIPOC, Indigenous and LGBQ2S+ writers, to attend my (free public) workshops and apply for a spot on my one-on-one consultation afternoons,” Tulchinsky explained. “I think Jews, People of Colour and queer and trans writers all have a lot to teach the mainstream world about our lived experiences. I want writers from under-represented communities to feel comfortable to come forward and let their voices be heard.

“Traditionally, Canadian literature has been dominated by white, straight, cis-gendered men (and a few women). We have a lot to catch up on. We all gain from a more diverse society and more diverse voices in Canadian literature.”

The residency will also allow Tulchinsky time for his own writing, principally, the first draft of a novel entitled Second Son, a family saga that draws on events in his own past.

The main character, Charly (formerly Charlotte) Epstein-Sakamoto, is a biracial, transgender man coming to terms with PTSD resulting from a tragedy that devastated his family decades earlier.

“The heart of the novel is based on my own journey transitioning from female to male, a child’s death in my family, and my experiences in a long-term, interracial, cross-cultural (Jewish-Japanese) relationship,” said Tulchinsky.

“Charly knows he’s a boy, even though his parents, his doctor, his teachers and all the other kids at school insist he’s a girl. When Charly’s brother (the first son and his only sibling) Joshua is killed in a tragic bike accident, his dad is so devastated he sinks into a deep depression, his mother begins an affair with her sister-in-law, and Charly finally begins to assert his true gender identity.”

Tulchinsky is also developing another novel, based on family stories and beginning in Russia in 1941.

“As I was writing the novel and researching the Holocaust, I started thinking about how many Canadians think the Holocaust began in 1939, with World War II, but the reality is the oppression of Jews by Hitler and the Nazis began years before the war, within days of Hitler becoming chancellor of Germany in January of 1933.

“I began writing another novel that begins in 1932, when Germany – Berlin in particular – was one of the most progressive places in the world. In Berlin at that time there were numerous gay clubs and cabarets, safe places for gay men, lesbians and trans people to gather, and the Jewish community was also thriving.

“That all changed overnight once Hitler came to power. I ended up with two new historical novels that I am still working on.”

Tulchinsky’s CV is lengthy, and one wonders how he has been able to be so productive.

“To be honest, part of my diverse career has to do with the fact that I found it impossible to survive as a novelist, even though I had numerous books published,” he said. “I am a graduate of the Canadian Film Centre in Toronto, which provides advanced training in film and television. Since then, I have worked as a writer and video editor on numerous television series. I have found it more possible to make a living in film and TV than I could as a novelist. The downside is I rarely have time to work on novels. This residency at the VPL is affording me time to write, which is a real gift.”

His advice to aspiring writers is be disciplined and tenacious.

“You need discipline to sit in a chair and write or you will never finish a novel. And you need tenacity to get your work published. Most writers get a lot of rejections before they find a publisher. Every time you get a rejection, just send your work out again,” he said.

Being Jewish and queer, Tulchinsky looks with growing dismay at what is happening today.

Twenty years ago, The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky reminded Canadians of a shameful history. It remains among the top 10 Canadian books ever borrowed from the VPL.

The Five Books of Moses Lapinsky follows a Jewish family living in Toronto’s Kensington Market in the 1930s and ’40s and is set against the backdrop of a massive antisemitic riot.

“On Aug. 16, 1933, at an amateur league softball game in Christie Pits park – a neighbourhood filled at the time with Jewish and Italian immigrant families – members of the antisemitic Swastika Club showed up with a giant swastika flag, which set off a riot between Jews and gentiles that involved 15,000 people and lasted throughout the night and is the largest race riot in Canadian history,” Tulchinsky said. “Unfortunately, with antisemitism, racism, transphobia and homophobia back on the rise throughout the world, the themes in the novel are just as relevant today as they were when I originally wrote the book.”

Tulchinsky thinks the current polarizing, often acrimonious, debate over sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) issues is “an effort on the part of the political right-wing to inflate the importance of cultural wars to distract people from the real issues we should be focusing on, such as climate change, wealth inequality and homelessness.

“I once saw a bumper sticker that read: ‘If you’re against abortion – don’t have one.’ I think it is the same when it comes to SOGI. If you are heterosexual and cis-gendered, you can either be an ally to the LGBTQ2S+ community and actively support us and fight for our rights, or you can leave us in peace.

“As an out and proud transman, I am just living my authentic life. And I hope I can serve as a positive role model to trans and non-binary kids who are struggling with their identity.”

Janice Arnold is a freelance writer living in Summerland, BC.

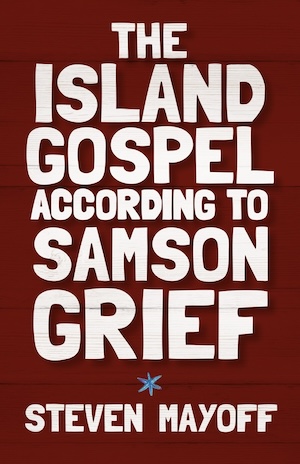

It is hard to describe simply the plot of The Island Gospel According to Samson Grief. The title character is a middling artist who, when we meet him, is struggling to finish a painting. Outside his window, he has just seen – after a break of 13 years – three figments of his imagination. The Figs, as he calls them, present themselves in the forms of Judas, Fagin and Shylock, and they have returned with an important mission for Grief.

It is hard to describe simply the plot of The Island Gospel According to Samson Grief. The title character is a middling artist who, when we meet him, is struggling to finish a painting. Outside his window, he has just seen – after a break of 13 years – three figments of his imagination. The Figs, as he calls them, present themselves in the forms of Judas, Fagin and Shylock, and they have returned with an important mission for Grief.