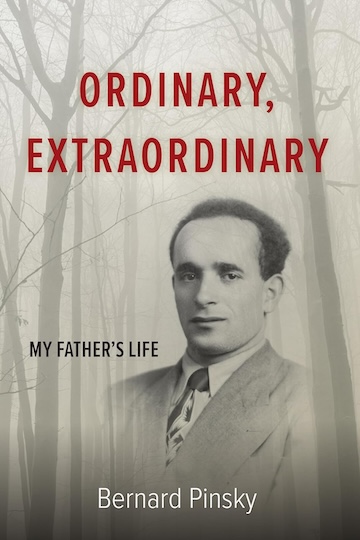

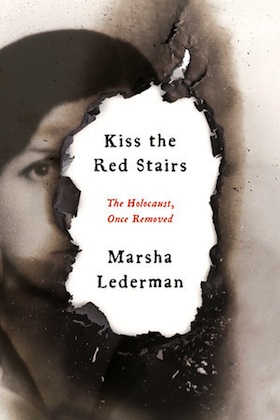

A photo Dekel Agami took Oct. 7, 2023, of Kibbutz Nir Oz in flames. (phot by Dekel Agami)

On Oct. 7, Kibbutz Magen, from which residents can see the Gazan city of Khan Yunis, was infiltrated by dozens of terrorists from Gaza. While two of the approximately 400 kibbutzniks were murdered and two seriously injured, a more horrific outcome was avoided, thanks to the heroic acts of a small squad of kibbutz civilian defenders, who held off the terrorists during a seven-hour gun battle.

A member of that response team was in Vancouver last week, sharing his story.

Kibbutz Magen is a kilometre away from Kibbutz Nir Oz, a village with a similar population, but which suffered exponentially more tragic outcomes that day – 46 Nir Oz residents were murdered and 71 taken hostage.

One reason for the less catastrophic death toll in Magen is that the terrorist infiltrators blew apart the perimeter fence a good distance from the kibbutz’s residential area. But the heroism and tireless response of Magen’s civilian emergency squad played a big role.

Dekel Agami, who grew up on the kibbutz, and his partner, Nufar Gal-Yam, who grew up in Sde Boker, the kibbutz most noted as the home of David Ben-Gurion, had moved in together on Kibbutz Magen on Oct. 4.

Since both had grown up in southern Israel, close to Gaza, the red alerts on Oct. 7 did not disturb them unduly. Around 7 a.m., Agami, an Israel Defence Forces veteran who served in the special forces, headed out with his weapon to meet other members of the security squad, a group of civilians and off-duty soldiers ranging in age from 20 to 70. He quickly realized this was not a routine day.

As he walked to meet his colleagues, Agami saw figures near the kibbutz border. The first one he encountered was wearing an Israel Defence Forces uniform – as numerous terrorists were that day – and so he did not shoot.

He came across the head of his security team, Baruch Cohen, who had been shot in the leg. As Agami was delivering first aid, an anti-tank missile hit the vehicle they were next to. Agami does not know how they survived.

In the event of an emergency, civilian and off-duty military personnel on kibbutzim are expected to manage on their own for 20 to 30 minutes until the arrival of the IDF. On Oct. 7, the dozen emergency squad members in Kibbutz Magen battled 30 to 40 terrorists on their own from 7 in the morning until 2 in the afternoon.

The terrorists breached the fence at a location relatively remote from the residential area of the kibbutz, giving the defenders a small tactical advantage. Fighting soon moved to the terrorists’ targets, the kibbutz’s homes, and, after providing first aid to Cohen, Agami fought the terrorists from one of the houses. The kibbutzniks successfully flushed the infiltrators back to the fence, where some of them fled – maybe back to Gaza, possibly off to murder easier prey.

During the fighting, Agami took a photo of nearby Nir Oz, where multiple plumes of smoke were rising in an ominous foreshadowing of their potential fate. The photo went viral in Israel.

“When I took this picture, I thought we were next,” Agami said to an audience at Temple Sholom on the evening of April 14. He and Gal-Yam also spoke at the weekly rally earlier that day, outside the Vancouver Art Gallery.

When the IDF finally made it to Kibbutz Magen, about 2 p.m., they killed the remaining terrorists. Then the larger trauma began to dawn on Agami and his fellow kibbutzniks.

Agami’s two daughters from a previous relationship were with their mother at a moshav a few kilometres away. During the battle, he didn’t worry about them – partly because, he said, he “couldn’t go there” but more because it never crossed his mind that the battle he was engaged in was part of a much larger crisis. When he finally did get in touch, he found out the three were safe.

The Magen fighters were too occupied keeping the terrorists at bay – Agami alone expended 15 magazines, about 450 bullets – to check their phones to see what was going on elsewhere. They did, though, have cellular connectivity, which was not the case in many kibbutzim. The terrorists were strategic, first targeting army bases and bringing down communications systems.

As the smoke cleared midafternoon on Oct. 7, several stunning realities came to light.

Three wounded residents – Cohen, Nadav Rot and Avi Fleisher – had been transported by the kibbutz doctor to a nearby community, from which they were helicoptered to hospital. Fleisher did not survive. Cohen would eventually have his leg amputated. No one – including those who made the journey – understand how they made it to safety. The terrorists had taken control of all the roads in the region, killing every Israeli they encountered. Even the military had not breached the area by the time the medical transport got through.

The exhausted kibbutz defenders soon discovered that what they had experienced was a comparatively small part of the worst terror attack in Israel’s history. In just a hint of the depths of preparation that went into the attacks, the fleeing terrorists left behind not only weapons, flashlights and food for an extended siege, but even supplies of blood for infusions.

Agami and Gal-Yam were brought to Vancouver by Itai Bavli, a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer in public health at the University of British Columbia. He and Dekel grew up together in Magen.

The friends estimate that 60 alumni of their regional high school died on Oct. 7. Including those killed in the subsequent war, they estimate 100 of their circle of friends are dead, including Bavli’s stepbrother, Tamir Adar, who lived in Nir Oz.

Agami downplays his heroism, but Bavli is emphatic.

“He saved my family,” Bavli said.

Gal-Yam, who is expecting a baby in July, just completed a five-month call-up as a major in the IDF. She and Agami are now in temporary accommodations on her home kibbutz of Sde Boker. Agami spent five months relocated in Eilat.

“It’s like some area after a hurricane,” Gal-Yam said of the chaos at Kibbutz Magen, which was founded in 1949 and is one of the oldest communities adjacent to the Gaza Strip.

She has since returned to her day job, but everything has changed, she said.

“It seems unimportant to do again whatever it was I was doing before Oct. 7,” she said, noting that creating a normal routine is impossible. “Nothing is normal now. I’m not normal. I’m a completely different person. We are living completely different lives than before. Nothing is the same. Nothing at all.”

The Israeli visitors demurred from making predictions about the political or military ramifications of events.

“Some people are going to have to give answers after all this will be over,” Gal-Yam said.

The length of time the hostages have been in captivity – more than six months – is something that was unimaginable on that first, terrible day, she said. “Not a person in Israel thought it would take more than six months to bring them home,” she said. “This is a reality none of us expected.”

An audience member asked how they view residents of Gaza now.

Bavli reflected on how, before Hamas took over the Gaza Strip, workers from Gaza came to their kibbutz, even staying overnight.

“People from Gaza worked on our kibbutz and were treated as family,” he said. “We wanted to have them as neighbours, to find political solutions, to find a way to live together.

“We don’t have anything against people from Gaza,” he said. “What broke our hearts was, at Kibbutz Nir Oz, the first wave [of infiltrators on Oct. 7] was Hamas, but the second wave was just people who came to steal. But they also killed people. That’s what broke our hearts, confused us.”

For the future, Bavli sees the willingness of Gazans to live in peace as key.

“Hopefully,” he said, “there are enough good people there to find a way to live together.”