Manfred Gottfried and a group of men on the stairs to the Dr. Sun Yat-sen mausoleum. (photo from VHEC: RA001-5-o7-5-9-0339x)

A little over 20 years ago, the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre started the Shanghai Oral History Project. Led by Roberta Kremer and Daniel Fromowitz, the project recorded the oral histories of Vancouver’s small Shanghai Jewish survivor community. They interviewed 10 survivors and/or their descendants, learning about their rich and unique experiences of survival in Shanghai.

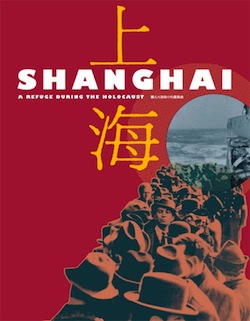

This project, along with loaned artifacts and memorabilia, became the basis for VHEC’s 1999 exhibition Shanghai: A Refuge During the Holocaust. It opened alongside another exhibition, Visas for Life: The Story of Feng Shan Ho. Both were well received, and included film screenings on the topic of Jewish refugees in Shanghai, and a demonstration of mahjong, a game which remains popular in the Jewish community in Vancouver. Once the exhibitions concluded, materials were returned to their lenders or safely placed under the VHEC’s care, and the interviews were catalogued and filed away.

In January 2022, I began my co-op position as digital projects coordinator with the VHEC. One of the first tasks assigned to me was to help improve accessibility to the Shanghai interviews and the audiotape transcriptions. In the 20 years since these oral history transcriptions were created, the VHEC has changed its digital file management and storage system. Some files were missing while others were mislabeled. Many files would no longer open within the current version of Microsoft Word. At the top of some transcriptions was a disclaimer: “The whole tape is not transcribed, only that which is related to Shanghai.” Throughout the transcriptions, comments like “(side discussions)” denote what the original transcriber believed to be unrelated to the subject matter.

Rummaging through these transcriptions, it became apparent that I would not simply be “tidying up.” By revisiting the Shanghai Oral History Project, my goal was to do more than just emphasize the unique experiences of this small group of individuals. As I listened to their interviews and transcribed their words, I wanted to offer a glimpse into how Shanghai Jewish survivors expressed themselves and reflected on their time in Shanghai, while also highlighting things that weren’t considered when the exhibition first opened 20 years ago.

On the list of possible interviewees for the Shanghai Oral History Project, George Melcor’s was the only name with “very elderly” added beside it in parentheses. Listening to George’s interview, it became clear that this would be a challenging transcription. George sometimes mumbled, which made it difficult to comprehend his words, or he would mix up his stories. But, for 88-year-old George, Shanghai left an impression. When asked by interviewer Daniel Fromowitz what memories of Shanghai come to mind, George lit up with excitement. “Shanghai was alive all the time. Never closed, always open.… Clubs and gambling, everything was free. Shanghai was a very free city.” At this point, the slow progression of the interview sped up: the emotions in George’s voice suggest that he was reliving his 16-year-old self. For a moment, George was not elderly.

What is striking listening to the Shanghai audiotapes is the dialogue between the interviewer and interviewee. Lore Marie Wiener was interviewed about her experiences in Shanghai by both Roberta and Daniel. But rather than just giving answers, Lore proceeded to converse with both interviewers, asking about where they were born, their experiences growing up and whether they faced antisemitism. Lore was also very reflective. She questioned the nature of Jewishness and what it consists of; she questioned “… why did we not interfere in Rwanda, and we do interfere in Yugoslavia?” With the former, there was a back-and-forth between Roberta and Lore, but, with the latter, Daniel was not sure how much to engage. These side stories provide a picture of Lore that is more than just her experiences of escaping the threat of Nazi violence and survival in Shanghai; it is the continuation of her life after the Holocaust.

Lastly, how did the interviewees recall, if any, their connection to the local Chinese and Japanese communities? In general, although interviewees were in Shanghai, Chinese people featured only in the background. They were acquaintances, as was the case for Anne Chick and the two Chinese kids living in her neighbourhood. For most interviewees who did interact with Chinese people, it was through a working relationship with Chinese servants, workers or amahs.

For Lore, she employed several Chinese tailors in her shop, as well as a chauffeur and a cook called Dun-zen. Interracial relationships were also possible. Kurt Weiss noted that, after divorcing his first wife, he had a Chinese girlfriend until he left Shanghai. Gerda Gottfried Kraus mentioned in passing how, in postwar Shanghai, one of her acquaintances married a Chinese woman and wanted to bring her with him to the United States. Knowledge of some Chinese, particularly Shanghainese, was also a common theme found in these interviews, though many interviewees state that they’ve either forgotten it after not using it for so long, or knew only the absolute basics. Additionally, they never learned how to read Chinese characters.

Knowledge of Japanese people was more limited. Kurt’s success as a suit salesman was due to his patron relationship with a Japanese engineer named Kato. Lore mentioned she was helped by a Japanese engineer when she and her mother were stranded in Harbin. But the one individual whom most interviewees referenced was Ghoya, the Japanese commandant of Hongkew ghetto. Ghoya developed a reputation as an unpredictable ruler: while Lore mentioned that her father and husband were treated well by Ghoya due to their academic connections, other interviewees mentioned episodes of violence committed by Ghoya and his guards against the Hongkew inhabitants. Their brutality is matched only by their treatment of the local Chinese. Most interviewees mentioned the mistreatment that local Chinese faced.

The experiences of Shanghai Jewish survivors are often overlooked when compared to those who survived in Europe. Lore was very concerned about this. At the end of her interview, she stated: “I’m not uncomfortable with anything. [But] … just try to be careful about the parts where I am too pleased with my life because there are so many people who suffered.” With the “global turn” in academic research into the Holocaust, the sub-category of “Shanghai survivor” has been gaining strength. It is a term that validates the experiences of refugee Jews and others who survived the Holocaust in Shanghai, while also acknowledging the unique circumstances and challenges they faced.

It is heartening to know that, in the 20-plus years since the VHEC’s Shanghai exhibition, research into this dimension of the Holocaust and the voices of these survivors have not been obscured, but, instead, have expanded into a vibrant subfield. By revisiting past projects and exhibitions, and making them more accessible, we can hopefully gean new information about the Holocaust and the multiplicity of survivors’ experiences.

Ryan Cheuk Him Sun is a PhD candidate in the University of British Columbia department of history. His research examines the entangled histories between Jewish refugees escaping Nazi oppression and the British colonies of Hong Kong and Singapore. He is also interested in the journeys that took Jewish refugees to East Asia, and their experiences in transit onboard ships and trains. He can be reached at [email protected]. This article was originally published in the VHEC’s Spring 2022 issue of Zachor.