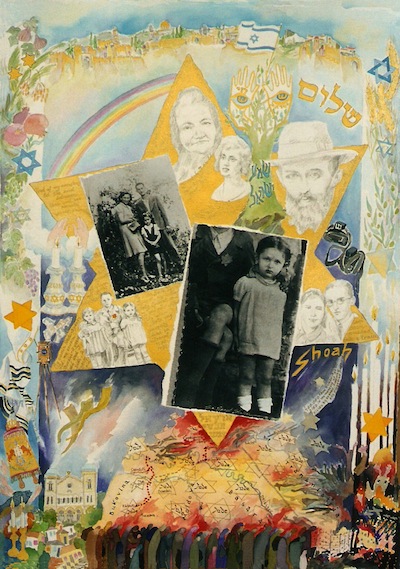

At the community’s commemoration of Yom Hashoah, child survivor Janos Benisz spoke about his experiences during the Holocaust. (photo by Rhonda Dent)

Over the past year, Janos Benisz has watched the news of Ukrainian parents fleeing to Poland and elsewhere in Europe to find safety for their families. While “overjoyed” for the families finding refuge today, he cannot help but reflect back eight decades to his own family’s catastrophic history in that violence-ravaged region.

Benisz was born in the summer of 1938 in the Hungarian city of Esztergom. He is one of the very few children to survive the Nazi concentration camps and is now one of an even smaller number of survivors alive to share their stories of survival. He spoke April 17 at the annual Yom Hashoah Commemoration presented by the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, on the 80th anniversary of the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Benisz lost his mother in 1943, when she was 38, after she went to hospital for a routine procedure but was, he said, murdered by a fascist there. His father remarried and his stepmother would prove a saviour for the boy.

The following year, the Nazis began rounding up Hungarian Jews and preparing to transport them to forced labour and death camps.

“Like a plague of locusts, the SS came marching into our city,” he recalled. “As they marched past our house, there was a great fear in our family. My father closed the windows and pulled the curtains down and his fear was passed on to me. The next day, we left our home and on the front of our white stucco home was a yellow Magen David. Within hours, an SS commander came to our house and put stickers on our valuables.”

His father took young Janos and his stepmother to relations who were Catholic. It was the last time he saw his father.

“Life was wonderful for six weeks until one of the neighbours reported us and informed that Jews were in this home,” said Benisz.

An SS officer accompanied by Hungarian Arrow Cross fascists knocked on the door and seized Janos and his stepmother, who were sent to the Strasshof concentration camp, in Austria. They remained there for eight or nine months, until liberated by Soviet forces. Benisz credits his stepmother’s determination for his survival.

“It was like a lioness protecting her cub,” he said. “She would go into the circle where the food was, or the slop was, with the big cup and she would always bring food to me. I would drink it and that sustained me.”

After liberation, Janos, 7, and his now-mother made their way back to Esztergom. The devastation was nearly total.

“I had many, many cousins and they all were massacred,” he said. “My mother’s family … it was like the earth had opened up and killed them all.”

The experiences left Janos’s stepmother mentally broken and Janos was placed in an orphanage.

“The only thing I remember is cod liver oil in the morning and brushing my teeth with about 10 or 15 guys beside me brushing their teeth as well,” he said. “After two-and-a-half years in the orphanage, somebody from the Joint [Distribution Committee] picked me up, took me to the train station. There were 14 or 15 other Jewish orphans there and they told us, ‘You’re going to America – North America.’”

The group first spent six months in France, where “they tried to educate us,” he said, but the young survivors were like “a bunch of wild animals.”

The group arrived in Halifax on Dec. 3, 1948. They were given hot soup and delicious sandwiches, as well as ice cream, of which Benisz said he must have eaten a gallon with his bare hands.

On the train across Canada, orphans disembarked at different cities and Benisz arrived in Winnipeg in the midst of a blizzard.

“My first Canadian Jewish home proved to be a disaster,” he said. “I was bounced around like a basketball between foster homes.… I was never part of the family. I was always an outsider.”

The terrors that followed him from Europe, which led to screaming in the night, did not make him a welcome addition to potential foster homes.

“Who wants to have a stranger’s scream waking [one] up every night?” he asked.

He was put in a reformatory for about six months before a Jewish welfare agency rescued him and found him suitable housing and got him caught up in his education.

At a young age, Benisz got a job as a copy boy at the Winnipeg Free Press. A life in the news business followed, especially covering sports, which he did at newspapers across Western Canada. An editor changed his byline from Janos Benisz to Jack Bennett, which became his professional designation.

Eventually, he arrived to a new job at a Vancouver daily just as the press launched what would become a year-long strike. Jack Diamond, the late Jewish businessman and philanthropist, gave Benisz a job. Years later, after a corporate buyout, Benisz had a $25,000 windfall and he and a partner opened a business in Gastown, “and, over the next 15, 18 years, we made a lot of money.”

He spoke of his gratitude for the community of survivors, especially the Child Survivors Group, based at the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. For two decades, he has spoken to school groups and others about his Holocaust experiences.

“I speak on behalf of the six million who have no voice, that includes 1.5 million children who were murdered,” he said.

At the commemorative event, Rabbi Dan Moskovitz of Temple Sholom reflected on the longer, formal name of the day, which is Yom HaZikaron laShoah ve-laG’vurah, Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day. He emphasized the resistance and revolt inherent in both the name of the day and the fact that Yom Hashoah is marked annually on the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

“Our sacred purpose is so much more important, so much more vital, because the life-memory is fading. We gather here this evening at the twilight of an era. As the Survivors’ Declaration hauntingly observes, the age of the Holocaust survivors is drawing to a close. Before long, no one will be left to say, I was there, I saw, I remember what happened…. It is in this void that the deniers and the distortionists will come, they always do, as they have continually on every night and every day since even before the liberation of the camps, to say that this didn’t happen, that it wasn’t so bad or the relativism of comparing trauma to trauma.”

There is one significant difference between the contemporary generation and the generation of the 1930s, said the rabbi.

“That difference is that we have the experience that they didn’t have. We know it can happen because it did,” he said. “We know the antisemitism, if it is not confronted vigourously, forcefully and immediately defeated, can develop into monstrous dimensions. So, we don’t have the luxury or the privilege to say, let’s wait and see how things will develop, how this turns out.”

The VHEC’s Abby Wener Herlin, granddaughter of survivors Aurelia and David Gold, spoke as a representative of the third generation.

“In our family, in order to build a life and live each day, they could not speak about their experiences,” she recalled of her late grandparents. “In order to protect themselves and us from the atrocities and traumas of their past, they shared very little.

“There is a sense of weight that comes from being the grandchild of Holocaust survivors,” Wener Herlin continued, “to know that I am part of the last generation that will ever hear those stories firsthand. I feel it is my duty and responsibility to carry it forward and it is my duty to remember.”

In a video presentation, former Canadian justice minister Irwin Cotler discussed the 1994 genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda, as well as the Holocaust, and said that what makes both historical instances so horrific are not just the horrors themselves but that both atrocities were preventable.

“Nobody could say that we did not know. We knew but we did not act,” said Cotler.

He addressed remarks specifically to survivors: “You have endured the worst of inhumanity, but somehow you found the resources of your own humanity, the ability to carry on, to build families and to make an enduring contribution to Canada and to the communities in which you settled.”

Corinne Zimmerman, board president of the VHEC, read from a statement Prime Minister Justin Trudeau released for Yom Hashoah and Moskovitz read a message from B.C. Premier David Eby. Sarah Kirby-Yung, Vancouver city councilor, read a proclamation from Mayor Ken Sim.

Cantor Yaacov Orzech chanted El Moleh Rachamim, the memorial prayer for the martyrs. An extensive musical program, produced by Wendy Bross Stuart and Ron Stuart, featured Bross Stuart on piano, Eric Wilson on cello, with Cantor Shani Cohen, Kat Palmer, Lisa Osipov Milton singing, as well as eight young voices collectively dubbed the Yom Hashoah Singers.

The evening was presented by the VHEC with the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver and Temple Sholom.