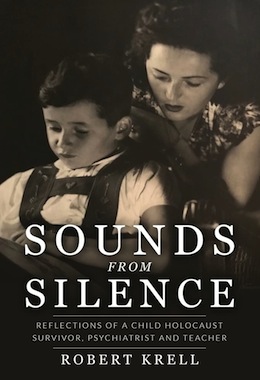

At 80, Dr. Robert Krell opens up in his new book.

Dr. Robert Krell, child survivor, psychiatrist, community leader and founding president of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, is probably known to most readers. But few people, perhaps even those closest to him, know him as well as they will after reading his extraordinarily vulnerable new memoir.

Krell acknowledges that he has held much back from the public and his closest family and friends. But, at 80, he has decided to open up in a book called Sounds from Silence: Reflections of a Child Holocaust Survivor, Psychiatrist and Teacher (Amsterdam Publishers).

Krell begins by talking about the duality of his life – the hidden child who, as an adult, tried to remain hidden versus the public figure whose career and community activities have placed him at the fore of various fields; the sadness at his core versus the upbeat visage he presents to the world.

“I have allowed family members and friends to see my inherent optimism and love of life. I live with few regrets,” he writes. “Blessed with a fascinating career, lasting friendships and an incredible family, I have kept at a distance my profound sadness, chronic fears, devastating shame, incapacitating shyness, and nightmares and preoccupations shaped by my earliest experiences and forged in an atmosphere of potential annihilation.”

Krell was 2 years old when his Dutch Jewish parents placed him in hiding with the Munnik family, who he would come to view as his actual parents. He was reunited at age 5 with his birth parents, Emmy and Leo Krell – a miracle on many fronts given the small proportion of Dutch Jews to survive to 1945.

“After liberation, life became very complicated,” he writes. He had been treated well by his rescuing family, unlike some Jewish children, “but strangely, even those ‘good’ circumstances exacted a psychological toll that never quite healed. After all, my relatively ‘benign’ circumstances were still completely off the scales of what is normal, including separation from my parents, shattering of security, and vague awareness of persecution that contributes to the feeling of shame experienced by a child as having done something wrong to cause the situation. Years later, as a child psychiatrist, I would see this phenomenon in children who, faced with parental separation, assumed responsibility.”

“After liberation, life became very complicated,” he writes. He had been treated well by his rescuing family, unlike some Jewish children, “but strangely, even those ‘good’ circumstances exacted a psychological toll that never quite healed. After all, my relatively ‘benign’ circumstances were still completely off the scales of what is normal, including separation from my parents, shattering of security, and vague awareness of persecution that contributes to the feeling of shame experienced by a child as having done something wrong to cause the situation. Years later, as a child psychiatrist, I would see this phenomenon in children who, faced with parental separation, assumed responsibility.”

His parents also survived in hiding and his mother in particular never stopped mourning the complete loss of both sides of their extended families.

“I was raised by psychologically wounded parents, no less so than if they had been in the camps,” says Krell. “For three years, they lived in fear of being caught, and that fear exacted a psychological toll that one cannot underestimate.”

Trying to recreate a life, they considered making aliyah to the new state of Israel, but their business before the war had been furs and the climate in Canada was more conducive to that specialty. They came to Vancouver in 1951.

Like many survivors, the Krells found new “family” at Schara Tzedeck Synagogue. Despite many survivors bearing a “burning rage against G-d,” the shul was a second home. His father refused to open a prayer book. And yet, years later, when he was in a position to be philanthropic, he spoke with Rabbi Mordechai Feuerstein and donated $30,000 to buy prayer books for the High Holy Days so that congregants wouldn’t have to carry them to and from synagogue on those days.

“Why would a man who no longer prayed purchase prayer books?” asks Krell. “The rabbi characterized Dad as ‘a man of faithful disbelief.’”

Habonim, the labour Zionist youth movement, was a major stabilizing force for young Robbie. He would attend weekend events, summer at Camp Miriam and do normal Canadian teenage things like matinees at the Stanley Theatre on Granville.

A late-in-life baby, his brother Ronnie, was born in 1956, and his mother’s disordered parenting shifted from the first born to the younger.

“Her subsequent attention to Ronnie grew so intense that even my 16-year-old self realized that he fulfilled her need to replay the years in which I had been lost to her. That need virtually enslaved my younger brother and freed me.”

While building a career as a clinical psychiatrist, professor and academic administrator, Krell and wife Marilyn were raising three daughters.

“I can barely believe that my survival as a young boy has led to the rebirth of an entire Jewish family that now includes nine gorgeous grandchildren,” he writes. “My good fortune scares me. Our world looks so dangerous, and the future of life – Jewish life – remains so precarious. But day-to-day, we are a close family, and every day brings much joy – so far.”

Krell was a leader in Canadian Jewish Congress regionally and nationally. In Vancouver, he became immersed in Holocaust remembrance and education. Kristallnacht commemorative lectures and other Holocaust remembrance events were often begun under the auspices of CJC.

With theologian William Nicholls and English literature teacher Graham Forst, Krell launched what has become a decades-long annual symposium for high school students on the Holocaust.

He was also among the first people anywhere to begin video recording the testimonies of Holocaust survivors.

Krell was also pivotal in the organizing of a succession of world conventions: first, for Holocaust survivors and, later, for “child survivors,” a term he acknowledges was not in use until the 1980s. Hidden children were not viewed as Holocaust victims in the way that survivors of the camps or partisan fighters were. Krell is among a small number of people who helped usher in a reconsideration of the wartime experiences of these children.

In 1984, he gathered 18 survivors and children of survivors in his living room and committed to creating a Holocaust education centre in Vancouver. But some of the older attendees remembered an as-yet unfulfilled promise to create a permanent local memorial to the Shoah, so the group decided to keep that commitment first.

“The memorial was unveiled on Yom Hashoah, April 26, 1987, in the presence of 1,300 members of the community,” notes Krell. “The survivors now had a metzeivah, a ‘burial site,’ albeit symbolic, to visit and to grieve.”

In 1994, the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre opened, with Krell as founding president.

One time, when he was on the national board of CJC, the organization considered ending their efforts to bring (by then aging) war criminals to justice.

“I argued for continuing the effort,” says Krell. “My measure of success was different. I told my colleagues that it was not only about successful prosecution but also their knowing that, one day, they might hear a knock on the door. The sleep of Nazis should be no less disturbed than that of Holocaust survivors.”

Throughout the book, Krell recalls brushes with history and the figures who make it.

On a trip to Israel as a young adult, he was able to get a seat at the Eichmann trial, thanks to an aunt who had married into the family of Gideon Hausner, the prosecutor of the case. On the same trip, Krell went to Sde Boker and ran into David Ben-Gurion.

A few years later, Krell volunteered to serve in the 1967 war as a doctor fresh out of his internship but, given the chronology of the Six Day War, by the time he got to Europe, the conflict was over.

Two years after that, on another trip to Israel, his plane was hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Krell was able to attend the ceremony when his family-in-hiding – Albert and Violette Munnik and their daughter Nora – were inducted by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations (posthumously for Albert).

Krell’s book evokes an array of emotions. The psychiatrist’s self-assessment provides a sometimes startling look inside.

“I kept my rage suppressed, not repressed,” he writes. “It was not unconscious. I knew that it was there. I felt in danger from it and feared losing control. I played, studied and worked hard, surrounded by good friends.”