The fourth edition of the Western Canada Jewish Book Awards, presented by the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival, culminated in a May 24 event at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver at which the winners in six categories – fiction, non-fiction, memoir/biography, children and youth, poetry, and Holocaust writing – were announced.

The fourth edition of the Western Canada Jewish Book Awards, presented by the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival, culminated in a May 24 event at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver at which the winners in six categories – fiction, non-fiction, memoir/biography, children and youth, poetry, and Holocaust writing – were announced.

Winning the Nancy Richler Memorial Prize for fiction was Simon Choa-Johnston for House of Daughters, a stand-alone sequel to The House of Wives. Based on the author’s family, this multi-generational family saga opens when Emanuel Belilios, a wealthy Jewish opium oligarch, suddenly leaves Hong Kong, and his junior-wife, Pearl, blames Semah, the senior-wife. Pearl kicks Semah out of the mansion where the polyamorous trio had lived and shuns everyone, including her daughter. This is a story of passions and regrets, wealth and survival, set in Eurasian Hong Kong’s high society.

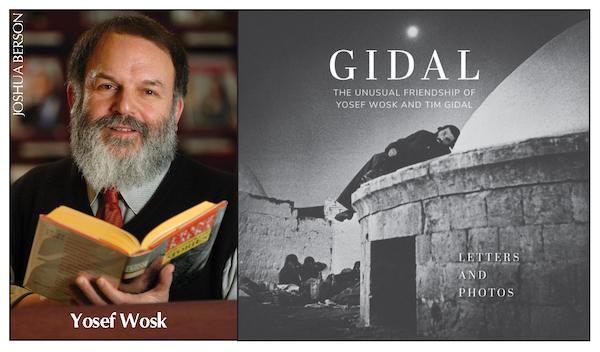

In the non-fiction category, the Pinsky Givon Family Prize went to Alan Twigg, editor of Gidal: The Unusual Friendship of Yosef Wosk and Tim Gidal, a selection of letters between Israeli Tim Gidal, a pioneer in photojournalism, and Vancouver scholar and art collector Yosef Wosk. In the late 1920s, with his handheld Leica, Gidal was able to travel in interwar Europe, capturing rare images of Polish Jews prior to the Holocaust. Wosk first encountered Gidal’s work in a magazine in 1991 – the photo “Night of the Kabbalist” captivated him. Wosk was determined to meet the photographer and eventually did. The two became close and the letters – selected by Twigg from hundreds the friends exchanged over two decades – both memorialize Gidal as an artist, scholar, historian of photography and “hero among the Jewish people,” and also capture the essence of Gidal and Wosk’s friendship.

In the non-fiction category, the Pinsky Givon Family Prize went to Alan Twigg, editor of Gidal: The Unusual Friendship of Yosef Wosk and Tim Gidal, a selection of letters between Israeli Tim Gidal, a pioneer in photojournalism, and Vancouver scholar and art collector Yosef Wosk. In the late 1920s, with his handheld Leica, Gidal was able to travel in interwar Europe, capturing rare images of Polish Jews prior to the Holocaust. Wosk first encountered Gidal’s work in a magazine in 1991 – the photo “Night of the Kabbalist” captivated him. Wosk was determined to meet the photographer and eventually did. The two became close and the letters – selected by Twigg from hundreds the friends exchanged over two decades – both memorialize Gidal as an artist, scholar, historian of photography and “hero among the Jewish people,” and also capture the essence of Gidal and Wosk’s friendship.

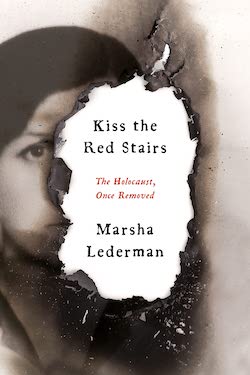

The Cindy Roadburg Memorial Prize for memoir/biography was given to Marsha Lederman for Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed. In it, Lederman delves into her parents’ Holocaust stories in the wake of her own divorce, investigating how trauma migrates through generations. At the age of 5, Lederman asked her mother why she didn’t have any grandparents, and her mother told her the truth: the Holocaust. Decades later, her parents having died and now a mother herself, Lederman began to wonder how much history had shaped her life and started her journey into the past, to tell her family’s stories of loss and resilience.

The Cindy Roadburg Memorial Prize for memoir/biography was given to Marsha Lederman for Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed. In it, Lederman delves into her parents’ Holocaust stories in the wake of her own divorce, investigating how trauma migrates through generations. At the age of 5, Lederman asked her mother why she didn’t have any grandparents, and her mother told her the truth: the Holocaust. Decades later, her parents having died and now a mother herself, Lederman began to wonder how much history had shaped her life and started her journey into the past, to tell her family’s stories of loss and resilience.

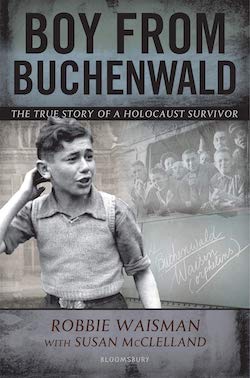

Boy from Buchenwald by Robbie Waisman (with Susan McClelland) took the Diamond Foundation Prize for children and youth writing. In 1945, Robbie Waisman, then Romek Wajsman, had just been liberated from Buchenwald, a concentration camp where more than 60,000 people were killed. He was starving, tortured and had no idea if his family was alive. Along with 472 other boys, these teens were dubbed “the Buchenwald Boys.” They were angry at the world for their abuse, and turned to violence: stealing, fighting and struggling for power. Few thought they would ever be able to lead functional lives again, but everything changed for Romek and the other boys when Albert Einstein and Rabbi Herschel Schacter brought them to a home for rehabilitation.

Boy from Buchenwald by Robbie Waisman (with Susan McClelland) took the Diamond Foundation Prize for children and youth writing. In 1945, Robbie Waisman, then Romek Wajsman, had just been liberated from Buchenwald, a concentration camp where more than 60,000 people were killed. He was starving, tortured and had no idea if his family was alive. Along with 472 other boys, these teens were dubbed “the Buchenwald Boys.” They were angry at the world for their abuse, and turned to violence: stealing, fighting and struggling for power. Few thought they would ever be able to lead functional lives again, but everything changed for Romek and the other boys when Albert Einstein and Rabbi Herschel Schacter brought them to a home for rehabilitation.

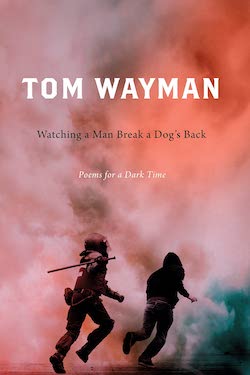

The Betty Averbach Foundation Prize for poetry went to Tom Wayman’s Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time, which explores the question of how to live in a natural landscape that offers beauty while being consumed by industry, and in an economy that offers material benefits while denying dignity, meaning and a voice to many in order to satisfy the outsized appetites of a few. A cri de coeur from a poet who has long celebrated the voices of working people, the collection also grapples with why “anyone, in this era so profoundly lacking in grace, might want to make poems – or any kind of art.”

The Betty Averbach Foundation Prize for poetry went to Tom Wayman’s Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time, which explores the question of how to live in a natural landscape that offers beauty while being consumed by industry, and in an economy that offers material benefits while denying dignity, meaning and a voice to many in order to satisfy the outsized appetites of a few. A cri de coeur from a poet who has long celebrated the voices of working people, the collection also grapples with why “anyone, in this era so profoundly lacking in grace, might want to make poems – or any kind of art.”

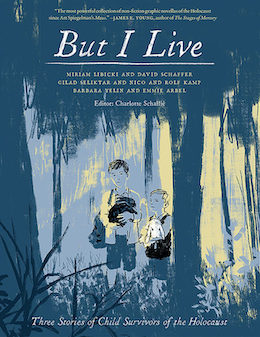

Rounding out the awards was the Kahn Family Foundation Prize for Holocaust writing, which was given to But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust by Charlotte Schallié (editor) and illustrators Miriam Libicki, Barbara Yelin and Gilad Seliktar. But I Live is a co-creation of the novelists and four Holocaust survivors: David Schaffer, brothers Nico and Rolf Kamp, and Emmie Arbel. Schaffer and his family survived in Romania due to their refusal to obey Nazi collaborators; in the Netherlands, the Kamps were hidden by the Dutch resistance in 13 different places; and, through the story of Arbel, who survived Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps, we see the lifelong trauma inflicted by the Holocaust. The book includes historical essays, a postscript from the artists and words of the survivors.

Each category in the 2023 Western Canada Jewish Book Awards was assessed by five jurors, in different configurations, from the following professionals: Linda Bonder, a retired librarian; Susanna Egan, professor emeritus of literature in English from the University of British Columbia; Dave Margoshes, who writes fiction and poetry on a farm west of Saskatoon; Norman Ravvin, a writer, teacher and critic living in Montreal; Rhea Tregebov, an author of fiction, poetry and children’s picture books, and a retired professor in the UBC Creative Writing Program; Elisabeth Kushner, a librarian and writer living in Vancouver; Karen Corrin, former head librarian of the Isaac Waldman Jewish Public Library at the JCC; Nicole Nozick, former executive director of the Vancouver Writers Fest and former director of the JCC Jewish Book Festival; and Anita Brown, who is working with the Waldman Library.

Each category in the 2023 Western Canada Jewish Book Awards was assessed by five jurors, in different configurations, from the following professionals: Linda Bonder, a retired librarian; Susanna Egan, professor emeritus of literature in English from the University of British Columbia; Dave Margoshes, who writes fiction and poetry on a farm west of Saskatoon; Norman Ravvin, a writer, teacher and critic living in Montreal; Rhea Tregebov, an author of fiction, poetry and children’s picture books, and a retired professor in the UBC Creative Writing Program; Elisabeth Kushner, a librarian and writer living in Vancouver; Karen Corrin, former head librarian of the Isaac Waldman Jewish Public Library at the JCC; Nicole Nozick, former executive director of the Vancouver Writers Fest and former director of the JCC Jewish Book Festival; and Anita Brown, who is working with the Waldman Library.

Daniella Givon, chair of the awards committee, introduced the May 24 event, sharing a bit about the awards and thanking all the sponsors and participants for the high calibre and diversity of the submissions. The winning authors then said a few words, and Dana Camil Hewitt, director of the JCC Jewish Book Festival, closed the proceedings with more thank yous, and an invitation for everyone to purchase and enjoy the books.

– Courtesy Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival