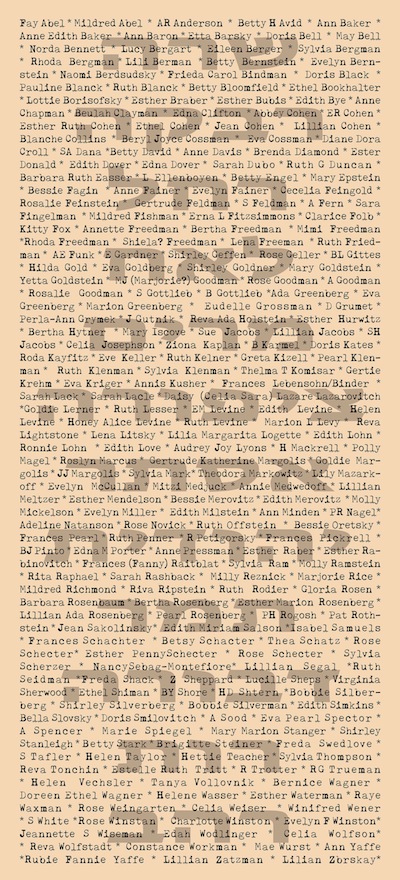

Grade 7 students at Vancouver Talmud Torah light memorial candles to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day. (screenshot)

Vancouver’s city hall, the Burrard Street Bridge and other landmarks around the city were lit in yellow light Jan. 27, as were buildings across the country, to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day. The commemoration coincided with the 77th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

Yellow was chosen, said Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart, to reflect the colour of the candles of remembrance being lit globally to mark the day.

“Antisemitism is on the rise around the world,” the mayor said before reading a proclamation on behalf of city council. “Vancouver has the opportunity to join with the Jewish community and all of our residents and Canadians from all walks of life in demonstrating our commitment to stand against antisemitism, hate and genocide.”

Stewart was joined by councilors Sarah Kirby-Yung, Pete Fry and Adriane Carr.

Kirby-Yung spoke of calls from constituents who have had swastikas drawn on their sidewalks or who have come across antisemitic graffiti in local parks.

“I’ve seen firsthand, when you go to work out at the gym or community facility, the need to post security guards, to have them at schools and daycares, at synagogues during times of worship,” Kirby-Yung said. “It takes all of us individually to stand up to discrimination. We need to continue to work together, collectively with our Jewish community, to ensure safety and inclusion for everybody.”

The Vancouver event was sponsored by the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA), the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC) and the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver.

Nico Slobinsky, Pacific regional director for CIJA, urged unity.

“Antisemitism is not just a Jewish problem, it affects us all,” he said. “Only by working together and standing up against antisemitism are we going to insulate all Canadians against the threat of hatred and racism in our society.”

Nina Krieger, executive director of the VHEC, noted that education about the Holocaust is at the heart of her agency’s mission.

“This mission is perhaps more urgent than ever as globally and in our own backyard we are encountering a rising tide of Holocaust denial and distortion,” Krieger said. “The latter includes actions or statements that seek to minimize, misrepresent or excuse the Holocaust. These assaults on the memory of the most well-documented genocide in history should raise alarms for all citizens of our diverse society. Online or offline, intentional or not, distortion of the Holocaust perpetuates antisemitism, conspiracy theories, hate speech and distrust of democratic institutions, all of which have reached new heights during the pandemic. Around the world, opponents of public health invoke Nazi policies to systematically persecute and murder Jews and others in order to depict themselves as victims and their governments as persecutors. Such outrageous comparisons are clearly inappropriate and deeply offensive to the victims and survivors of the Holocaust.”

Dr. Claude Romney, a child survivor from France, spoke of her father’s survival during 34 months in Auschwitz – an unimaginable expanse of time in a place where the average life expectancy was measured in days. (Romney’s experiences, and those of her father, Jacques Lewin, were featured in the April 7, 2017, issue of the Independent: jewishindependent.ca/marking-yom-hashoah.)

Prior to the streamed event, Grade 7 students at Vancouver Talmud Torah elementary school lit candles of remembrance. King David High School students Liam Greenberg and Sara Bauman ended the ceremony with a musical presentation.

Earlier, another ceremony was livestreamed from the National Holocaust Memorial in Ottawa. Emceed by Lawrence Greenspon, co-chair of the National Holocaust Memorial Committee, the event featured ambassadors and Canadian elected officials and was presented by CIJA, the National Capital Commission, the embassy of Israel in Canada and the Jewish Federation of Ottawa.

Shimon Koffler Fogel, chief executive officer of CIJA, said the day of remembrance is intended to be as much “prospective as it is retrospective.”

“As we remember, we also reaffirm our resolve to combat the hatred that still plagues our world today, perhaps more so than at any time since those dark days of the Shoah,” he said. “There is an urgent imperative to sound an alarm and refuse to let its ring be silenced. Hate is no longer simmering in dark corners, relegated to the discredited margins of civil society. It has, in many respects, increasingly asserted itself in the mainstream public square. It has become normalized.

“Countering hate speech is both a necessary and essential imperative to preventing hate crime,” he said. “So let us resolve, collectively here today and across this great country, to give special meaning to our remembrance by fulfilling the pledge, ‘never again.’”

Israel’s ambassador to Canada, Ronen Hoffman, told the audience that his grandmother’s entire family was murdered in the Shoah. He denounced the misuse of that history.

“Any claim, inference or comparison to the Holocaust that is not in fact the Holocaust only acts as a distortion to the truth of what happened to the victims,” he said. “Invoking any element of the Holocaust in order to advance one’s social or political agenda must be called out as a form of distortion and, indeed, denial.”

Germany’s ambassador to Canada, Sabine Sparwasser, noted that, in addition to the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, it was also recently the 80th anniversary of the Wannsee Conference, where the “Final Solution” was devised.

“No country has a greater responsibility to learn from the past and to protect the future than Germany,” she said. “Remembrance is the only option. This sacred duty is the legacy of those who were murdered and of those who survived the horrors of the Shoah and whose voices have gradually disappeared. The greatest danger of all begins with forgetting, of no longer remembering what we inflict upon one another when we tolerate antisemitism, racism and hatred in our midst.”

Other speakers included Ahmed Hussen, minister of housing and diversity and inclusion; the American ambassador to Canada, David L. Cohen; Mayor Jim Watson of Ottawa; Andrea Freedman, president and executive director of the Jewish Federation of Ottawa; and Dr. Agnes Klein, a survivor of the Holocaust.