We’re experiencing a transformation in Winnipeg – one that holds hands with truth and reconciliation. Recently, a statue of Queen Elizabeth II, newly restored, was put back on a plinth in front of the Manitoba Legislature. The media showed it, fixed and shiny, and reported on the cost of repair. The next day, it was vandalized again.

Two years ago, on Canada Day, protesters knocked down two statues, those of Queens Victoria and Elizabeth II. The statue of Queen Victoria was too damaged to repair; its pedestal was covered with the protesters’ red handprints, like the blood of all the Indigenous children lost. It was both vandalism and art installation, a painful reminder of the clash between colonialism and Indigenous suffering in our country.

This struggle is ongoing and Winnipeg spells it out through violence, poverty and discrimination. Much of the time, the discrimination appears invisible to those who don’t witness it, but it’s there. I’ve admired the strength of one Indigenous activist, Vivian Ketchum, who described being followed around in a drugstore on June 11, 2023, by a security guard – an older woman, she didn’t hesitate to discuss this fact with the much younger security guard and then resolved the issue with the manager. A day later, the CBC featured a story that also included Ketchum, this time describing how, when an Indigenous woman goes missing, the friends and family must go looking for her themselves because, even after reporting, the police don’t appear to be listening or helping.

Being a witness is something I’ve been learning as I study Daf Yomi, a page of Babylonian Talmud a day. In Gittin, the Tractate about divorce, there’s an extended discussion among the rabbis about the get (a Jewish divorce document), how it should be written, delivered and witnessed for a valid divorce. It turns out that practically anyone can write the document, but the divorce is not valid unless specific parts are personalized, delivered and witnessed in front of the right people. The witnesses and the act of witnessing the document being signed are the important parts.

As a writer, it doesn’t matter what I write if no one reads and “witnesses” it. Having an audience offering the right kind of respect or interest matters for those who produce content. The written word, on its own, doesn’t automatically have importance. It’s the relationship between the readers and the words that matters.

This notion of “being in relationship” is also part of what it means to be a treaty people, bound by the agreements made between Indigenous peoples and Canadian settlers. Relationships are a two-way stretch. It takes work on both sides to change and make a difference.

Here’s a personal example of “being in relationship.” Years ago, I had a traumatic experience with a close long-time friend. The friend ghosted me. She disappeared, without explaining why. It caused harm. I spent years trying to reach out, apologize and mend things. I couldn’t understand what had happened. I was deeply hurt.

Eventually, I realized that it takes two people to be friends. One person cannot do it on her own. A friendship is a relationship. If only one person is relating, there is no friendship. This realization enabled me to stop trying to fix things. Instead, I mourned the loss and moved on. To my surprise, about 15 years after this “break up,” this friend sought my forgiveness. We’ve worked towards a new relationship ever since. It will never be the same, but we’re both trying.

Although this wasn’t a marriage breakup, it contained enough parallels that it helped me gain a deeper understanding of failed relationship and the need for Jewish rituals to cope with it. The Jewish rituals around divorce and the giving or receiving of a get are far from perfect. They are deeply flawed in the ways that men can maintain power and control over their wives – only men can give women a divorce in this religious model. Yet, for many, the ritual has deep value.

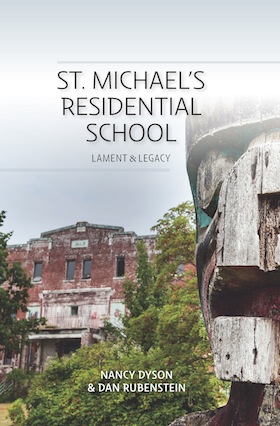

In Winnipeg, there are individual efforts to make relationships and try to push reconciliation forward. It’s a difficult process. It’s not happening with enough speed. Like other relationships in our lives, it takes work. We must fix broken systems to acknowledge the ongoing racism around us. When the government mended the statue of Queen Elizabeth and erected it back on the Manitoba Legislature grounds, it wasn’t done with the necessary relationship work in place. Almost immediately, the statue was labelled with spray painted words like “Colonizer” and “Killer.” While some find this disgraceful vandalism, others see it as no less than the truth. Queen Elizabeth reigned over Canada during a time in which residential schools still held control over many Indigenous peoples, harming and sometimes killing their children and families.

If we’re in relationship with others, we have to be open to seeing others’ worldviews. This is only possible when we witness others’ needs and stand ready to serve others as part of a bigger community. Yes, someone needs to write a get, a Jewish divorce, but, without appropriate witnesses, it cannot become a valid divorce. When we witness others’ needs at their most painful moments, giving them validity, together, we’re in a meaningful relationship.

In past years, the Winnipeg Canada Day celebration at the Forks included fireworks. After the news about the deaths of so many children at residential schools, the Forks changed its Canada Day focus. While there are still July 1 events at the centre of our city, they’re now more attached to Indigenous practices and meaning. This year, elders will open the event with a ceremony and a sacred fire. The day’s activities will be full of diverse cultural programming. Instead of fireworks, there’s a drone show, with 100 drones, to honour Indigenous teachings and tell stories about the stars.

It takes healing, ritual and forgiveness to get through serious trauma or to mend fractured relationships. Canada Day is still an important part of who we are as a country. Standing witness is an essential part of Jewish practice. Remembering how we Canadians got here, as a treaty people, in a relationship, can make our celebration more meaningful for everyone.

Joanne Seiff has written regularly for CBC Manitoba and various Jewish publications. She is the author of three books, including From the Outside In: Jewish Post Columns 2015-2016, a collection of essays available for digital download or as a paperback from Amazon. Check her out on Instagram @yrnspinner or at joanneseiff.blogspot.com.