Passover is coming! As we prepare, we think of what it means to be enslaved and to be free. Some seders focus on human rights. Others read and discuss Jewish texts about how to understand the holiday. Every year, we re-examine not only how good the foods are, but the ideas around slavery and redemption.

At one of my first Jewish events in Winnipeg, 10 years ago, I heard racist comments about indigenous Canadians. I was really upset by the incident. I was so uncomfortable that I still remember the experience in detail, even though I’ve forgotten a lot of other things over time.

I recently attended some of the lectures in an extremely worthwhile series put on by Westworth United Church called Interfaith Dialogue on Truth and Reconciliation. Each year, in the springtime during Lent, this church offers some of the best adult education programming I’ve ever attended and they welcome the entire community. The topics are thoughtful but, even more important, participants come ready to wrestle with hard intellectual and emotional ideas. I was introduced to it because Dr. Ruth Ashrafi has been a speaker as part of this programming more than once, and I’m hooked.

This year, the series was held in four different locations throughout the community, including Congregation Etz Chayim, Westworth United Church, as well as at one of the mosques and at a Buddhist Temple. It was so well attended that it filled the pews – wherever it was held.

Each session, a religious leader spoke, but he or she spoke at the lectern of a different congregation. Dr. Shahina Siddiqui spoke at Etz Chayim. Ashrafi spoke at Westworth United. It was powerful to see people of different faiths take to different pulpits. These leaders spoke, in the context of their religious traditions, on their status as Canadians or newcomers to a place with a heavy past of racism toward and discrimination and neglect of its indigenous people.

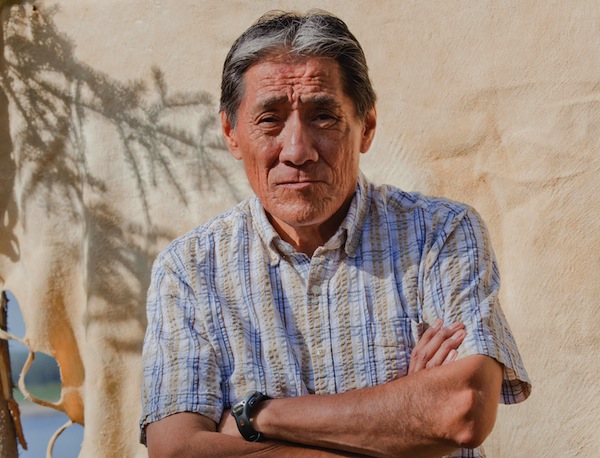

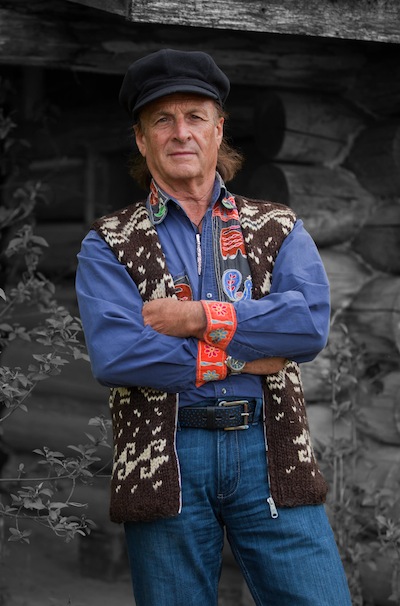

The most shattering part of the series was to hear from indigenous elders. I only attended two of the events, and heard Theodore Fontaine and Chickadee Richard speak. I cried while I listened to them. Their powerful personal, political and religious stories shook me.

These were bright, strong leaders with absolutely valid points about how they and their communities have been affected and mistreated by Canadian law and society. Their beliefs and prayers – about caring for Mother Earth, about protecting water and guarding the lives of those they love – are no different than those of other religious traditions in Canada. Yet, there are still indigenous communities who are forced to live in terrible conditions, without access to clean water and without adequate education or health care. How can people of faith accept this dichotomy? How is it that the first people in Canada don’t have access to the basic human rights that most of the rest of us enjoy?

After each set of lectures, we were sorted into random discussion groups. In the first event, we were asked to imagine what it might have been like to experience residential school and how we felt we would have reacted. What would that have been like?

All around me, I heard older Canadians mention how they didn’t know, and that their history classes didn’t teach them what had happened. They struggled with this part of Canadian history. It’s a denial that seemed familiar from German accounts of the Second World War, when people said “they didn’t know” what was happening to the Jewish people in their communities.

I could see many parallels between the stories Theodore Fontaine told, of “going to the moon” and escaping the abuse by disassociating and going somewhere else in his mind, and the novel The Painted Bird, by Jerzy Kosinski, which describes the horrors experienced by a Jewish child during the Holocaust. Trauma causes us (humans) to do many of the same things, even if our religious and ethnic identities differ.

Many of us know that the trauma of the Holocaust doesn’t go away in one or two generations. Those indigenous Canadians who were sent away from their families to residential schools, where they were abused, fed poorly and otherwise mistreated – their trauma has affected their families for generations. Jerzy Kosinski dealt with his childhood Holocaust trauma through substance abuse and, eventually, suicide. It’s no wonder that many indigenous survivors do the same.

Passover is a time of year, like the High Holidays, where we throw off wrongs and bitterness in the hope of embracing new growth and change. We can throw off the bondage of old biases or ideas that have enslaved us. Prejudice against indigenous people, their traditions and the burden of past abuses needs to be addressed – by all of us.

At the end of the lecture series, the facilitators asked variants of this question: “What will you do in the next year to address reconciliation, promote diversity and inclusion, and to make change?” My commitment was to be brave in speaking out about these issues.

Now, I’m turning over the question to you. What will you do, as a person of faith, to make change? Start by reading the 94 recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Call to Action. Write to your politicians to protect the water, the earth and the peoples who came to Canada first. Go to a powwow or a reconciliation discussion. Look others, no matter who they are, in the eye and greet them with loving kindness. In short – do more. It’s the Jewish thing to do.

Remember – we were slaves in the land of Egypt and now we’re free. Free to step up, speak up and help others along the path to equal rights, respect and freedom.

Joanne Seiff has written regularly for CBC Manitoba and various Jewish publications. She is the author of three books, including From the Outside In: Jewish Post Columns 2015-2016, a collection of essays available for digital download or as a paperback from Amazon. See more about her at joanneseiff.blogspot.com.