If the occupation is going to end with the help of North American Jews, it will be owing to the growing force of millennials who stand up not only for their own rights, but the rights of others.

One of these individuals has taken to social media via a series of parody videos to get her message across. As Avi Does the Holy Land prepares to launch its second video-log season, I’ve been thinking about its creator, Calgary-raised Aviva Zimmerman. When I was first alerted to “Avi’s” Facebook page, I admit I was fooled. “Arab workers literally BUILDING the Tel Aviv boardwalk. And they call us a racist country?!! #TelAviv #coexistence,” she wrote. I nearly shot back in anger to the mutual friend who had acquainted us, before taking a closer look. Satire is supposed to cut close to the bone, and that’s certainly what Avi Does the Holy Land does.

In the v-log’s first season, “Avi,” a sexed-up Canadian Jew who “went on a Birthright trip and fell in love with Israel,” skewers Israeli treatment of liberal Zionist critics, Israel’s shoddy treatment of Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers, Tel Aviv’s party scene as counterterrorism policy and Israeli LGBTQ policy as used in the government’s PR campaigns. A successful Indiegogo campaign for season 2 has now expanded to raising funds for a live show.

“Avi” is one type of millennial Jew – though, of course, a larger-than-life version. The differences in opinion and action among millennials regarding Israel, however, are real, ranging from those trying to burnish Israel’s image abroad via an uncritical look at the country to those trying to tarnish every image of the country. But there is a healthy cadre of young Jews deploying a sense of solidarity with their own, as well as with the oppressed.

Some young Jews are gravitating to Open Hillel, to encourage a more pluralistic discourse about Israel on North American campuses, or to the Centre for Jewish Nonviolence, which takes young Jews to the West Bank for projects in solidarity with Palestinians resisting settler encroachment. At the University of British Columbia, there’s the Progressive Jewish Alliance, which bills itself as “a group of progressive Jews committed to creating a new, vibrant, independent Jewish space.”

And there’s IfNotNow, whose anti-occupation mission has expanded into resisting the many moves of Trump’s administration. IfNotNow declares on its website, “Just as Moses was commanded to return to Egypt and fight for the liberation of his people, we, too, feel called to take responsibility for the future of our community. We know the liberation of our Jewish community is bound up in the liberation of all people, particularly those in Israel and Palestine.” Recently, IfNotNow created a hashtag called #ResistAIPAC. “When the Trump Administration Goes to AIPAC, the Jewish resistance will be there to meet them,” the site says.

With the message of Passover soon upon us again, we might best consider how to raise children whose connection to Israel can be transformed into one pushing for rights and freedom for all.

Mira Sucharov is an associate professor of political science at Carleton University. She is a columnist for Canadian Jewish News and contributes to Haaretz and the Jewish Daily Forward, among other publications.

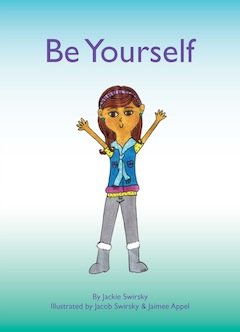

Enter her book, Be Yourself, with illustrations by Jacob and Swirsky’s sister-in-law Jaimee Appel. It can be purchased at beyourselfbook.ca.

Enter her book, Be Yourself, with illustrations by Jacob and Swirsky’s sister-in-law Jaimee Appel. It can be purchased at beyourselfbook.ca.