A still from the documentary Fiddler’s Journey to the Big Screen.

The Vancouver Jewish Film Festival runs March 3-13, and features more than 30 films, all of which will be available online for the duration of the festival. As always, there are shorts and features, fictional narratives and documentaries – presenting a great diversity of perspectives. This month, the JI offers readers a peek into the lineup.

Fifty years of Fiddler

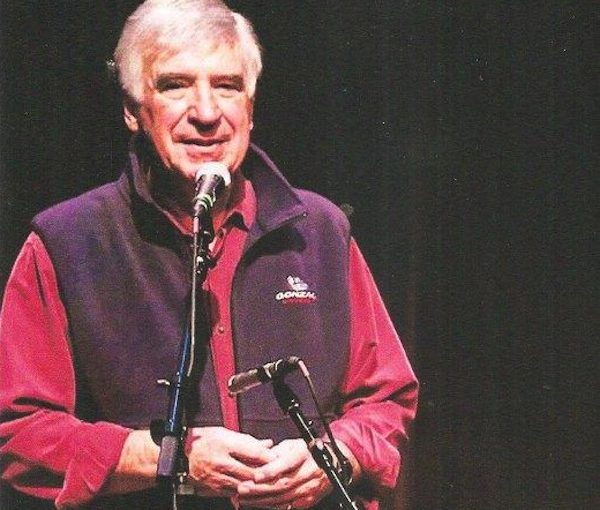

Like a lot of people, Norman Jewison thought Norman Jewison was Jewish. When he was growing up in Toronto’s east end, other students would call out, “Hey Jewy!” Decades later, when he was one of Hollywood’s acclaimed filmmakers, it would come as a shock to many that someone with the word Jew as the root of their surname was, in fact, not Jewish. It hit Jewison earlier, when he tagged along to synagogue with one of the only actual Jewish kids in his school.

“When the melamed at the temple told me to leave, I thought, ‘What’s going on?’” he said. “Where do I belong?”

The feature-length documentary Fiddler’s Journey to the Big Screen purports to tell the story of how the stage play based on Sholem Aleichem’s Anatevka tales turned into the cinematic blockbuster Fiddler on the Roof. It does that, but it is also very much a story of Jewison’s trajectory as an interpreter of historical and current events.

Jewison had already made a splash with his 1967 race-focused movie In the Heat of the Night when he conjured the idea of filming Fiddler. Friends and foes predicted failure. Too Jewish. Not a large enough potential audience. But Jewison forged ahead, certain that his version would universalize the story into “a film for everybody.” Arriving at a time of social upheaval in the United States and elsewhere, Fiddler’s underlying themes were relatable to many, Jewish or not.

Case in point: the film was huge in Japan. There may be next to no Jews in that country, but, in the early 1970s, when Fiddler was released, Japanese society, like many countries, was struggling to balance modernity and tradition.

The documentary Fiddler’s Journey to the Big Screen comes a half-century after Fiddler on the Roof’s screen debut. It interviews surviving contributors and actors, many of whom saw their early careers explode with the popularity of the movie. Rosalind Harris, now 75, played Tzeitel both on Broadway (after understudying for Bette Midler) and in the film. Her thrill at the film and her place in it is undiminished by time and she nearly steals the documentary.

The enthusiasm of Jewison himself seems equally undiminished. He tells of how he sought out Isaac Stern, perhaps the 20th century’s greatest violinist, to dub the music of the titular character. He dismissed Frank Sinatra’s entreaties to play Tevye and scored Topol, the Israeli actor (né Chaim Topol), who had played the lead in Israel and then in London, casting aside, in the process, Zero Mostel, Broadway’s longtime Tevye.

Diplomatic relations with the Soviet bloc at the time made it impossible to film in Ukraine, where Anatevka is set, so Jewison struck a deal with the “non-aligned” Yugoslavia and much of the filming took place in Lekenik (now in Croatia), in wooden buildings constructed based on historical architectural records. One commentator in the documentary notes the irony that the film about a disappeared community was filmed in what is now referred to as “the former Yugoslavia” – “another place that is no more.”

Jewison speaks emotionally about watching the film’s Israeli debut beside Golda Meir and a meeting he had with David Ben-Gurion, who told Jewison that whoever is crazy enough to choose to be a Jew is Jew.

“If I’m crazy enough to want to be Jewish, then I’m Jewish,” Jewison interprets Ben-Gurion’s words.

But when he received an Academy Award, he cheekily acknowledged the truth. “Not bad for a goy,” he joked.

Not bad for a Canuck, one might add.

The documentary’s director, Daniel Raim, will participate in a live Q&A on March 7, 7 p.m.

Shorts of all sizes

Since this year’s Jewish Film Festival is online and on demand, you can choose to view the numerous short films as a binge or watch one or two between features as a sort of visual amuse bouche.

At about 30 minutes, Paradise is on the long end of the “shorts” spectrum. It features Ala Dakka, who will be recognizable to Fauda fans, as the doe-eyed Palestinian boxer, Bashar. In real life, Dakka is an Arab Israeli who, in media interviews, has been open about his struggle with his identity. In this film, he plays Ali, who has just arrived at Eilat airport from his home in Berlin, to attend his sister’s wedding. After a fight over the phone with his father (it was cheaper to fly to Eilat than to Tel Aviv, so now he is going to miss the pre-wedding dinner), he decides to skip the festivities altogether and hitchhike to the Sinai. (This after a five-hour interrogation by border security at the airport, which doesn’t help either Ali’s frame of mind or his ability to make the celebratory banquet.)

Picked up by a group of Israeli partiers, Ali opts to introduce himself as Eli, and so begins a subtle and, of course, inevitable succession of miscues and small betrayals. It is a tightly told story of self-identity and the perceptions of others. Dakka is a rising star in Israeli film and he brings memorable depth to his character in this short, charming drama. A subtext of the film is the happy-go-lucky Israelis’ perceptions of Egypt (or perhaps the broader “other”) and a degree of paranoia that one of the party crowd acknowledges doesn’t require pot-smoking to ignite.

A slightly shorter film, at about 20 minutes, is Pops, which pits grieving siblings against each other, as they try to do what they each think their recently deceased father would have wanted regarding his burial. The uptight son and the hippy-ish daughter come to an unorthodox compromise.

You’re Invited sees a rabbi’s daughter invite her friends to a funeral when she learns that the deceased has no kin. Charming in concept and cheesy in execution, with uneven acting and heavy-handed writing, the short film is sweet enough, although anyone who has been a pallbearer will recognize an empty box when they see one carried in a movie. Explicitly based on a true story, the 13-minute film is neither too long nor too short.

For a quick laugh, at seven minutes, The Shabbos Goy follows a religious woman as she deals with the unexpected activation of a personal electronic device – a very personal electronic device – during Shabbat lunch. She runs into the street to find a non-Jew who she can entice but, due to halachah, not overtly request to turn the humming device off before the men in the house discover the source of the noise. (The women of the house, notably, remain blasé.)

The Jew who defended Nazis

Ira Glasser was the director of the American Civil Liberties Union from 1978 to 2001, a period when the organization exploded in size and relevance – and also when it took on some of the most contentious topics the country has ever faced.

Perhaps not a household name, Glasser and his contributions to civil liberties in particular and to American society more broadly are examined in the documentary feature Mighty Ira.

It is easy to admire Glasser in theory and to support his principles in principle. It is harder to swallow when he champions what Oliver Wendell Holmes termed “freedom for ideas we loathe.” This challenging conflict is at the heart of Glasser’s life’s work and the heart of the film.

Glasser’s vigilance for justice was born at Ebbets Field, the now-disappeared home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, which Glasser calls his cathedral. The Dodgers were gods to the kids in Glasser’s Flatbush neighbourhood, no less so when Jackie Robinson integrated major league baseball, in 1947. At age 9, Glasser discovered that Robinson was forced to stay in hotels and eat at restaurants apart from his teammates while on road trips to parts of the country. That injustice stirred in young Ira a lifelong mission.

But devotion to racial equality can seem to come head-to-head with First Amendment rights to free expression, as when neo-Nazis sought to march in the Chicago suburb of Skokie, Ill., in 1977. The provocative plan to wear fascist regalia and parade through a town whose population was half Jewish – and which included one of the world’s largest communities of Holocaust survivors – was thwarted by town officials, who used a backdoor ordinance to prevent the event. (There was a 500-member B’nai B’rith chapter in town at the time, all of whose members were survivors.)

Glasser’s ACLU took up the case, and the backlash against the unpopular cause was enormous. It tested the mettle of the ACLU leadership – to say nothing of their fundraising department – and their commitment to free speech. But the leadership, which included a great many Jews, were almost unanimously steadfast.

The documentary shows how the ACLU’s relevance grew in the time of Glasser’s leadership, not solely because of his actions but also because the country was struggling with a range of social and moral conflicts. While the rights group had been at the forefront of issues like the Scopes “Monkey Trial” (addressing the place of religion in public education), the internment of Japanese-Americans during the Second World War and Brown v. Board of Education (banning school segregation), the ACLU’s docket really filled up in the time Glasser was at the helm in large part because the country was confronting and struggling with so many divisive issues.

Mighty Ira is the story of a remarkable man, but it is also a history of American free speech in the second half of the 20th century.

Director Nico Perrino will be a guest at the March 9, 1 p.m., screening of the documentary.

More information about the festival will soon be available at vjff.org.