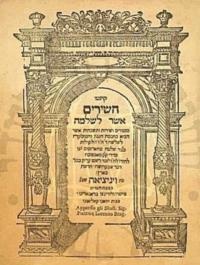

The documentary Hebreo: The Search for Salomone Rossi (Joseph Rochlitz, 2012) introduced last year’s Vancouver International Film Festival audiences to Profeti della Quinta, a Switzerland-based Renaissance and early Baroque vocal ensemble, primarily composed of Israelis. It followed the quintet to the Italian town of Mantua, the birthplace of Salomone Rossi, the first-known – and elusive – early-17th-century composer of Jewish music, who also was “one of the most renowned composers and performers at the court of the Gonzaga dukes.” The film’s audiences were treated to the ensemble’s musical preparations ahead of their concert of Rossi’s works at the Palazzo Te, where his music might have originally been performed, as well as by illuminating commentary from historians and musicologists on Rossi’s music and its impact.

On a North American tour to support their latest recording, Il Mantovano Hebreo, featuring Italian madrigals and Hebrew prayers by Rossi, Profeti della Quinta is in Vancouver Feb. 2, presented by Early Music Vancouver at Vancouver Playhouse. The first half of the program includes a screening of the 45-minute 2012 documentary; the program continues with the live performance of Rossi’s music. Members of the ensemble appearing in the Vancouver recital include Doron Schleifer and David Feldman, cantus; Lior Leibovici and Dan Dunkelblum, tenor; Elam Roten, bass and musical direction; and Orí Harmelin, chitarrone (a large bass lute).

Rotem, the ensemble’s music director, who also composes and plays the harpsichord in addition to the bass, spoke with the Independent about the quintet’s newest release, the experience of making the film, and their upcoming recording Rappresentatione Di Giuseppe E I Suoi Fratelli (Joseph and His Brethren), a “musical drama in three acts sung in biblical Hebrew,” Rotem’s composition for the ensemble set to be released in March.

Jewish Independent: When and how was Profeti della Quinta established?

Elam Rotem: Profeti della Quinta started while I was still in high school. Around the age of 17, I fell in love with vocal music, and especially the music of the 16th and 17th centuries. It was shortly after that I collected some of my friends and started singing Latin motets in the corridors of the school. The early sacred music that we were singing was a very odd element in an Israeli kibbutz school, but I think that our fellow students liked it.

Later, we were lucky to add Doron Schleifer, who can sing perfectly the soprano lines of 16th-century music and has a most beautiful and unique voice color, different from any other countertenor I know. After a pause, when I was in the army, I studied music in Jerusalem and then joined Doron in Basel in the schola cantorum – one of the best schools specializing in early music. There, we found new colleagues. Not so surprisingly, most of them are from Israel, too. (In this particular tour, we are all Israelis, but in others, it’s not always the case.)

JI: Can you talk about the experience of making that film about Salomone Rossi and what it was like, ultimately, to play his music at the palazzo?

ER: It should be noted that we are definitely not the first to sing and play Rossi’s music – not at all. His Hebrew sacred music is quite common in Israeli choirs’ repertoire, and was also performed and recorded in America. Rossi’s instrumental music is played in many concerts of 17th-century music. However, with our historically informed performance approach, we try to get closer as much as possible (and this is not simple) to the way Rossi’s music may have been performed in his time. Our special combination of knowledge in early music and in Hebrew allows us to read Rossi’s Hebrew music in its original notation (this is something worth seeing and we welcome people after the concert to have a look in the scores).

Moreover, in our new album, Il Mantovano Hebreo, we shed light on Rossi’s most neglected repertoire – his beautiful Italian madrigals. Singing in the palaces of Mantova [Mantua] where Rossi worked 400 years ago was an amazing experience for us. We look forward to further experiences like that in Italy!

JI: Can you speak to what role, if any, music plays in “illustrating” Jewish history?

ER: As far as I understand, the Hebrew music of Rossi is a very local phenomenon that probably stopped not much after its creation, probably around Rossi’s death (circa 1630). Other compositions in Hebrew came up only much later in music history, and not in Italy. However, this was a very interesting point in history – a Jewish musician succeeds in breaking the barriers of society, becomes successful and accepted, and then goes back to his own community and tries to revolutionize the music of the synagogue. In Rossi’s own words, to share with God the talents that were given to him.

JI: There seems to be a movement to work to “uncover history” through performing the work of composers who were (or nearly were) “erased” by history. Can you comment on the experience and responsibility of performing “neglected” music? How does Profeti della Quinta approach this enterprise? How do you make this music accessible to contemporary audiences?

ER: Profeti della Quinta are privileged to be (at least) the third generation of the “early music movement.” However, we believe that if music is “only” forgotten, that alone is not a good enough reason to bring it to life. We believe in good music, and when we find such good music, we want to share it with others. This was exactly the case with Rossi’s Italian madrigals. The purpose of music in the early 17th century was to move the listeners, and this is exactly our aim, as well.

JI: Profeti della Quinta achieves “vivid and expressive” performances by “addressing the performance practices of the time.” Can you explain a little bit more about that approach? Do you try to recreate an experience or to create something entirely new?

ER: This is an important point – it is not possible to recreate early music exactly the way it was done. This is simply because we cannot know fully how it was done. However, there are many things we can do. We strive to understand the compositions better (historical counterpoint and composition techniques), to understand the way music was performed (historical notation, ornamentation practices) and, as much as we can, also the social context and the meaning the music had in the time of its use. Nevertheless, we are aware that what we are doing is a new creation, mainly inspired by the past.

JI: What are some of the challenges of your dual role as music director of the quintet, as well as being one of the musicians?

ER: This is, in fact, quite simple: Before the concert I’m the musical director, but during the concerts I’m one of the performers. The concerts are the easy and fun part!

JI: I’m curious about your composition about Joseph and his brothers. Can you describe what it’s like to compose in Hebrew, while “using the musical language and context” of Italian Renaissance composers? Mazal tov on the recording’s upcoming release!

ER: Thanks, we are all very excited about the coming release of Rappresentatione Di Giuseppe E I Suoi Fratelli (Joseph and His Brethren). Concerning the language, I merely followed Rossi’s footsteps. He was the first to use the Hebrew language within the Christian musical language of his day. For Joseph and His Brethren, I also used the musical language of the early 17th century but with a focus on the newly invented dramatic genre – the opera. It’s a Hebrew Orfeo, if you like! (I intentionally don’t say “Jewish”; the Old Testament’s stories belong to whole of the Western culture. Luckily for me, it’s my mother tongue in which it was originally written, and I’m excited to share it.)

JI: Many leading Israeli classical musicians leave Israel for Europe. How difficult is it to achieve an international reputation while based in Israel? Do any of you participate in the Israeli expat community in Europe?

ER: This is a difficult question. Being in the middle of Europe makes … traveling around relatively easy, and this economical aspect is crucial today. For example, we performed in the U.K. only once, after … winning in the York competitions. We got several calls, but none of the organizers were able to pay the travel [costs]. The situation would have been much more difficult if we were coming every time from Israel.

JI: Your February concert with Early Music Vancouver will be paired with a screening of the documentary film. What’s it like to perform alongside yourselves, as it were?

ER: We love performing next to the screening of the film. The audience actually knows what [they are listening to] and, therefore, enjoys and is moved much more from our performance. It is related to what “early music” is – the more you understand the context, the stronger your experience is. We are looking forward very much to this tour!

Profeti della Quinta is in Vancouver, Feb. 2, 3 p.m., at the Playhouse; there is a pre-show chat at 2:15 p.m. Early Music Vancouver has recently introduced half-price tickets for concert-goers 35 years of age or younger, and rush seats for students with valid ID are $10 at the door. For information and tickets, visit earlymusic.bc.ca.