Tekhiyas ha-meysim, resurrection of the dead, is not an everyday occurrence. But it happens in literature when attention is once again focused on long-neglected authors. Scott Davis, editor and publisher of Storyteller Press, is one of those resurrectors. He has rediscovered the prolific and bestselling 19th-century Yiddish writer, Jacob Dinezon, who was friendly with “the Big Three,” the founding fathers of modern Yiddish literature – Mendele Mocher Seforim, Sholem Aleichem and Y.L. Peretz – and has brought him back.

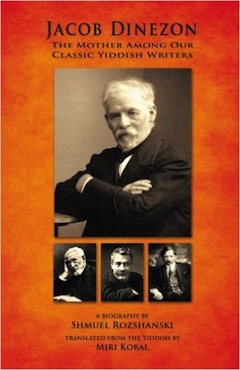

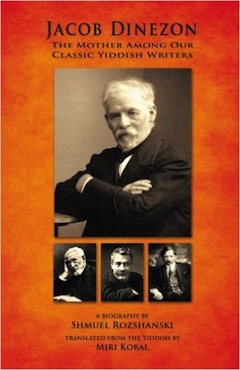

So far, four works by or pertaining to Dinezon have been published by Storyteller Press: Memories and Scenes, a collection of stories and reminiscences (2014); two novels, Yosele (2015) and Hershele (2016); and, now, the 1956 biography Jacob Dinezon: The Mother Among Our Classical Yiddish Writers by Argentine Yiddish writer Shmuel Rozhanski, translated by Miri Koral.

I must confess that, even though I took an advanced degree in Yiddish literature at Columbia University, I had never once heard mention of Dinezon – until Davis came along a couple of years ago and resurrected him. But now, when one scrolls through an internet site for Peretz, one sees not one but two photos of Dinezon; one with Aleichem and Peretz, the other, with Peretz alone.

Dinezon was friendly with Peretz for a quarter of century. In 1890, he published, at his own expense, Peretz’s first book, Bekante Bilder (Familiar Pictures), when it was rejected by all other publishers, and he presented the entire printing to his friend.

Rozhanski’s book is not exactly a biography in the classical sense. In fact, he doesn’t even tell us in what year Dinezon was born. Rather, the author focuses on Dinezon’s books and the interaction between them and the author’s life. It may more properly be called a literary biography, with a summary and gentle analysis and evaluation of Dinezon’s works.

Dinezon, who was born near Kovno, Lithuania, and died in Warsaw in 1919, was one of the most popular Yiddish writers during the 19th century, when Yiddish literature flourished in Eastern Europe. His novel The Dark Young Man sold more than 200,000 copies. Every Jewish household had his books but, because of the sentimental nature of his work, his reputation has fallen into neglect. He was considered passé because critics felt he pandered too much to women readers and other lovers of romances. Today, he might be considered the author of soap operas or pulp fiction. And yet, a respected Yiddish writer placed Dinezon and Aleichem on the same plane, calling the former lachrymose and the latter funny – and both writers of the folk.

In Rozhanski’s book, we learn of the spiritual and linguistic struggle that Yiddish works had to undergo from the middle through late 19th century, when proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment, the Haskalah, sought to highlight Hebrew belles lettres and diminish Yiddish. Among these maskilim were Mendele, who wrote in Hebrew and Yiddish, and Aleichem, who began in Hebrew but then switched to Yiddish.

Dinezon, too, was torn between the two languages, and this inner battle is aptly depicted in one of his letters. There, he states that when he writes in Hebrew and uses phrases from Isaiah or Ezekiel, he feels that the prophets are speaking for him. But, when he writes in Yiddish, he feels that he is speaking for himself and that his protagonists are speaking in their own authentic voices.

This is perhaps the best description of the inner conflict that 19th-century writers who knew both Hebrew and Yiddish had to face. The usual explanation for dropping Hebrew and returning to Yiddish – this was Aleichem’s position, for instance – was the more practical one that the Jewish masses in Eastern Europe knew Yiddish far better than Hebrew and, hence, the readership was very limited. But Dinezon’s literary explanation penetrates the heart of the artistic problem of choosing one or the other of two Jewish languages.

Rozhanski calls Dinezon “mother” for his gentle nature. Once, when Peretz devastated a young writer whose short story he had read by telling him, “Enough! You have no talent,” Dinezon, who was present, called the young man aside and told him to try again; perhaps his next effort would be better.

Rozhanski calls Dinezon “mother” for his gentle nature. Once, when Peretz devastated a young writer whose short story he had read by telling him, “Enough! You have no talent,” Dinezon, who was present, called the young man aside and told him to try again; perhaps his next effort would be better.

But Dinezon had the courage to criticize Mendele, whom Aleichem called the “zayde,” the grandfather, of Yiddish literature. Dinezon called Mendele too much of a purist regarding use of the Yiddish lanuage. He felt the language of the plain folk should be used. And Rozhanski claims that Dinezon’s goals were more moralistic than artistic; hence, Dinezon criticized Mendele’s satires, regarding them as humor without any moral lesson.

Indeed, it was the moral lesson and a practical uplift of society that Dinezon had in mind when he published Yosele. In this short novel, he criticized the cruel educational methods used by teachers in the small-town cheders. This novel prompted calls for reform, helped modernize pedagogy and led to the inception of more secularly minded schools for youngsters.

The biographer contends that Dinezon’s creativity shouldn’t be measured by his books alone. His work for orphans, his translation of Heinrich Graetz’s History of the Jews from German into Yiddish, even though Graetz didn’t want his work “desecrated” by having it in jargon, and his thousands of letters to writers and social activists – all of these Rozhanski considers part of Dinezon’s creative accomplishments.

So modest a man was Dinezon that, once, at a literary event in honor of Peretz, Peretz pointed to Dinezon in the audience and said, ”My holy soul is this man … this man.” At this, Dinezon rose and denied Peretz’s kind remark by saying that the inspiration comes from within Peretz himself.

Dinezon was a lifelong bachelor. At one point in his life, he was, like Aleichem, a tutor to the daughter of a wealthy man.

Like Aleichem, he fell in love with the girl and the girl’s love was reciprocated. But, whereas Aleichem ended up marrying his pupil, Dinezon was denied his love.

Nevertheless, despite this setback, he continued to serve the wealthy man in other trusted capacities.

In 1913, when Aleichem was ill in Europe – he would immigrate to the United States in 1914 – Dinezon wrote him a letter revealing a plan. When Aleichem would feel better, he would join Peretz and Dinezon and all three writers would go to Palestine and walk the land and write a book about their adventures. “So get well soon,” Dinezon concludes.

This dream was never realized.

For this slim in-depth literary biography, Rozhanski assiduously mined letters, newspapers, magazines, Yiddish writers’ memoirs, critical evaluations, as well as all of Dinezon’s published works, to draw information about the writer, in his own words and in the estimation of others.

Curt Leviant’s most recent books are the novels King of Yiddish and Kafka’s Son.

Glinert also traces the changes in the use of the language from biblical times through the Mishnah (before and after 200 CE), where the Hebrew of that period was more direct and seemingly more colloquial, as can be seen by comparing a text from the Mishnah with any chapter in the Bible. During the next two or three hundred years, written Hebrew then moved on from the Hebrew-only Mishnah to the two-language Talmud, with its mix of mostly Aramaic and much less Hebrew. (In all of this, of course, we only have written texts to go by.)

Glinert also traces the changes in the use of the language from biblical times through the Mishnah (before and after 200 CE), where the Hebrew of that period was more direct and seemingly more colloquial, as can be seen by comparing a text from the Mishnah with any chapter in the Bible. During the next two or three hundred years, written Hebrew then moved on from the Hebrew-only Mishnah to the two-language Talmud, with its mix of mostly Aramaic and much less Hebrew. (In all of this, of course, we only have written texts to go by.)

He attends Columbia, majors in English literature and edits the school’s literary magazine. Later, he gets a yearlong fellowship to Cambridge, where, for the first time in his life, he gets a whiff of antisemitism. He is aware of the “casual antisemitism that punctuates English literature,” but that’s in books and here was real life. The English Jews he met, Gottlieb notes, considered themselves “the other,” and he, too, senses the English disdain of foreigners and Jews.

He attends Columbia, majors in English literature and edits the school’s literary magazine. Later, he gets a yearlong fellowship to Cambridge, where, for the first time in his life, he gets a whiff of antisemitism. He is aware of the “casual antisemitism that punctuates English literature,” but that’s in books and here was real life. The English Jews he met, Gottlieb notes, considered themselves “the other,” and he, too, senses the English disdain of foreigners and Jews. Have I Got a Story for You is a beautifully produced book, from the stunning, colourful cover, the fine introductions by Glinter and novelist Dara Horn and, of course, the lively fiction. Even the clever title, Have I Got a Story for You, resonates with Yiddish braggadocio.

Have I Got a Story for You is a beautifully produced book, from the stunning, colourful cover, the fine introductions by Glinter and novelist Dara Horn and, of course, the lively fiction. Even the clever title, Have I Got a Story for You, resonates with Yiddish braggadocio.

Rozhanski calls Dinezon “mother” for his gentle nature. Once, when Peretz devastated a young writer whose short story he had read by telling him, “Enough! You have no talent,” Dinezon, who was present, called the young man aside and told him to try again; perhaps his next effort would be better.

Rozhanski calls Dinezon “mother” for his gentle nature. Once, when Peretz devastated a young writer whose short story he had read by telling him, “Enough! You have no talent,” Dinezon, who was present, called the young man aside and told him to try again; perhaps his next effort would be better. The poems of Leivick (1886-1962) range in subject matter: a poem about a very small poem “no longer than an epitaph”; the recollection of a birch rod beating given by his father; a prisoner in a cell at night “swallowing as if it were wine the moon’s bright light”; a man looking for work without success. Leivick was a paperhanger when he came to the United States. He was also a noted playwright; his most famous is The Golem, originally produced by Habima Theatre when it was still in Moscow, and later translated into other languages.

The poems of Leivick (1886-1962) range in subject matter: a poem about a very small poem “no longer than an epitaph”; the recollection of a birch rod beating given by his father; a prisoner in a cell at night “swallowing as if it were wine the moon’s bright light”; a man looking for work without success. Leivick was a paperhanger when he came to the United States. He was also a noted playwright; his most famous is The Golem, originally produced by Habima Theatre when it was still in Moscow, and later translated into other languages.