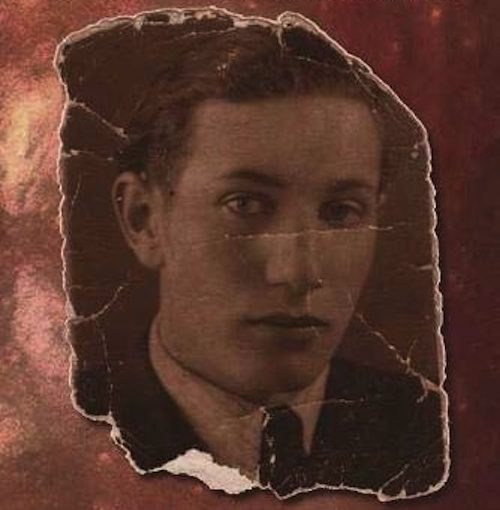

From the page before the opening of Moishe Rozenbaumas’s incisive, heart-felt memoir, we already feel the pain that will inhere in much of his story. Even before we begin reading this autobiography, we see a photocopy of the author’s dedication, handwritten in Yiddish, to the memory of his mother and three brothers, with the dates they were murdered by the Germans’ Lithuanian collaborators in August 1941, in Telz, where Rozenbaumas (1922-2016) was born.

Many people know Telz as the name of the famous yeshivah that was located there, but The Odyssey of an Apple Thief (Syracuse University Press, 2019) by Rozenbaumas – translated from the French by Jonathan Layton and edited by Isabelle Rozenbaumas – takes us into the city, depicting a vibrant Jewish culture, zeroing in on housing, way of life, learning and sports. The title comes from little Moishe’s sneaking into the bishop’s orchard next door and nabbing apples, and the author gives us an historian’s sweep of an area, with a memoirist’s penchant for detail.

For instance, his description of a middle-class household’s Sabbath meal. Although Jews lived “in poverty, hand to mouth,” middle-class Jews had munificent Sabbath meals. Typical to Eastern European towns, the housewife prepared the cholent pot at home, then brought it to the baker, whose oven was heated all Friday night long throughout the Sabbath. Then, around noon on Shabbat, the woman would go and pick up her cholent. Most Jews didn’t have the sort of meals that Rozenbaumas describes, which are at odds with the reigning poverty in Telz.

When the Germans occupy Lithuania, Rosenbaumas accents the avid cooperation between the Lithuanians and the Germans, who murdered 90% of Lithuania’s Jews. He writes that the situation of the Jews in Lithuania was no worse than in other countries; they weren’t loved but they were tolerated. However, in the very next sentence, we read that once, when the president of Lithuania addressed an antisemitic rally, he said that nobody should be stupid enough to slaughter a productive cow while it’s still giving milk.

Rozenbaumas provides what he considers a needed reassessment of the yizkor bikher, the memorial books that survivors of various towns assembled after the Holocaust, which always accented the people’s “piety, purity and morality,” even though there were all kinds of individuals. What is often omitted from these yizkor bikher, Rosenbaumas states, is the miserable poverty of Jews who lived in lightless cellars, had only black bread dipped in powdered sugar for food, froze in winter, and dressed in rags.

Rozenbaumas provides what he considers a needed reassessment of the yizkor bikher, the memorial books that survivors of various towns assembled after the Holocaust, which always accented the people’s “piety, purity and morality,” even though there were all kinds of individuals. What is often omitted from these yizkor bikher, Rosenbaumas states, is the miserable poverty of Jews who lived in lightless cellars, had only black bread dipped in powdered sugar for food, froze in winter, and dressed in rags.

During the financial crisis in the late 1920s, his father’s successful fabric shop began slipping. Rather than declaring bankruptcy, the father ran away to Paris, where he had sisters. Despite continuing promises, the father never sent any support to his wife and children, and was unaware of what happened to his family until after the war.

Without a father, the author’s mother and her four boys slowly sank into poverty and hunger. Rozenbaumas becomes an apprentice to a poor tailor with 10 children who live in squalid quarters. Soon, he is the sole breadwinner for his family. But, when the Germans invade, he flees eastward to the Soviet Union, just like his father had fled westward. But the author doesn’t notice the irony of the breadwinner again fleeing alone. True, Rozenbaumas asks his mother to come, but she refuses; he doesn’t ask any of his brothers to join him in his flight.

In the Soviet Union, life wasn’t easy. First, Rozenbaumas served four years on the front, undertaking dangerous reconnaissance missions; he was wounded and decorated several times. He regrets that Jewish former soldiers from other lands never mention the half million Jews who fought with the Red Army, including hundreds of Jewish generals and other high-ranking officers.

When Rozenbaumas’s unit liberates Lithuania, first thing he does is go to his house in Telz, where he finds Lithuanians occupying his now-emptied home. He learns where his family was massacred and longs for revenge, which soon comes. After volunteering as a translator for the Russians, he gets the satisfaction of hunting for the Lithuanian murderers, finding them, watching their trials and immediate executions. He even found the murderer of his youngest brother, Leybe, “who may have been,” Rozenbaumas adds, “his playmate.”

When Rozenbaumas finally decides to leave communist-controlled Lithuania, he describes the nightmare of leaving, taking the great risk of paying an exorbitant fee for forged papers that would guarantee his exit. He makes it, finally, across the border into Poland, with suspense and fright accompanying him like a second skin. It was not until he got to Vienna that he could breathe freely.

One day, Rozenbaumas met a man who knew about his father in Paris and thus was able to find him. But the father-son relationship was uneasy. The father never expressed a word of emotion regarding the murder of his wife and his three sons.

Coincidence also plays another crucial role. Rozenbaumas, by chance, bumps into his old girlfriend, Roza, and later marries her.

Rosenbaumas concludes his touching narrative with the hope that the stories of the European Jewish civilization that was brutally erased from the face of the earth will not be forgotten.

Curt Leviant’s most recent novel is Katz or Cats; Or, How Jesus Became My Rival in Love.