With her latest book, Olga Campbell sets out to leave a legacy, one that encompasses the trauma of the past but also the richness of the present and hope for the future.

Dear Arlo: Letters to My Grandson is Campbell’s third book. Her first, Graffiti Alphabet, comprised photographs of graffiti she found around the Greater Vancouver area. Her second, A Whisper Across Time, was her family’s Holocaust story.

Dear Arlo: Letters to My Grandson is Campbell’s third book. Her first, Graffiti Alphabet, comprised photographs of graffiti she found around the Greater Vancouver area. Her second, A Whisper Across Time, was her family’s Holocaust story.

The first essay in Dear Arlo is about Campbell’s parents, Tania and Klimek. They lived in Warsaw. “They were surrounded by family and friends and had much to look forward to,” writes Campbell. “Then, in 1939, everything changed. The Nazis invaded Poland from the west, the Soviets from the east. Life as they had known it stopped.”

Klimek would be arrested by the Soviets first, a pregnant Tania two weeks later. They were sent to different Russian prison camps. They survived, but the baby didn’t, nor did any of Tania’s family, most notably, her twin sister and parents, Campbell’s maternal grandparents.

“Several months after their release from the prison camps, my parents found themselves in Baghdad, Iraq,” writes Campbell. “By that time, my mother was pregnant with me and could go no further. I was born in Baghdad on February 14, 1943.”

Eventually, after living in both Palestine and the United Kingdom, the family came to Canada. It wasn’t an easy life, learning a new language and new culture, or a long one for Campbell’s mother, who died at 52 of cancer.

Campbell shares her stories and wisdom with readers as a grandmother speaking to her only grandson, Arlo, with whom she obviously has a special relationship.

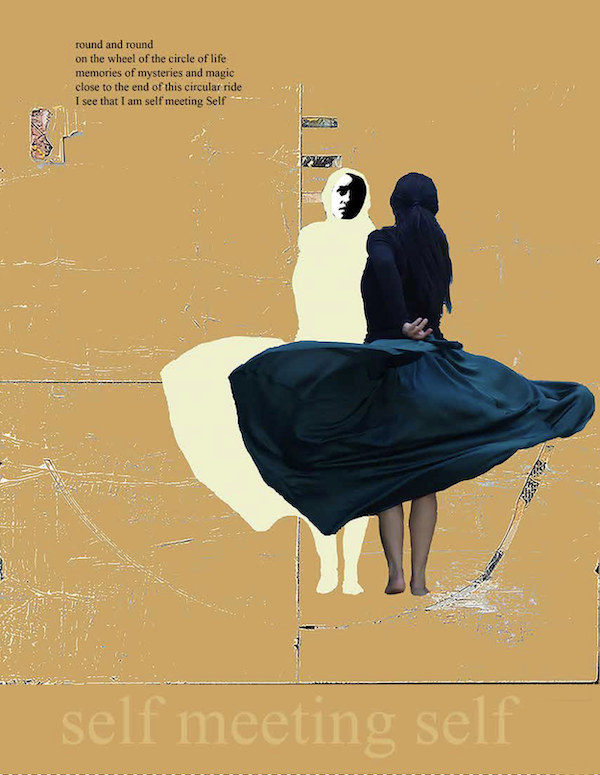

“I am writing this book as a legacy for you,” she writes in the first letter to Arlo. “A multidimensional memoir. A compilation of my writing, my art and a few family recipes. These writings and art are my responses to events in my life. The losses, trauma, grief … and the joy, happiness and love. It’s about the angst and awe of life, which is ever-changing, full of challenges but also magical.”

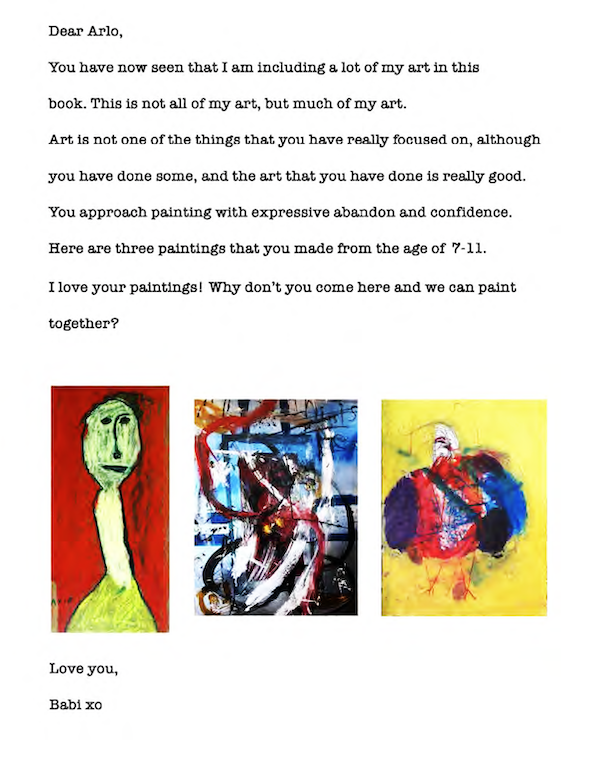

Brief letters to Arlo are spread throughout the memoir, which is gloriously full of Campbell’s artwork – painting, mixed media, sculpture and more, all of it in colour. A graduate of Emily Carr University of Art + Design, she has had many exhibitions since deciding to become an artist in her 40s, having started her professional life as a social worker. She has participated in the Eastside Culture Crawl since its inception almost 30 years ago, and has been a consistent part of the West of Main Art Walk (Artists in Our Midst) as well.

In addition to the art and letters in Dear Arlo, Campbell includes some of her poetry and essays. She shares how she came to write her second book, her experiences dealing with intergenerational trauma, her path to spirituality, how she found courage, and more.

She writes about losing her husband, in 1994. “Along with him, my plans and dreams for the future also died,” she writes. He died of a stroke at 49 years old – the pair had been together for 32 years, married for 26 of those years.

She shares the story of how she came to have her current dog, Nisha. “I was very sick in September 2019 with what my doctor now believes was COVID, before anyone had heard of COVID,” writes Campbell. Struggling many months with breathing difficulties, she turned, in desperation, to Ganesha, a Hindu god. “My wish to him was to remove all obstacles to my physical, emotional and mental well-being.”

A couple of days later, there came a knock at her door. Two work acquaintances were there, asking if she could adopt a rescue dog. Campbell did, and Nisha “was extremely timid, jumping, trembling and shaking at every sound, every movement. I held her all day every day for the first week to calm her down and get her used to me. She is still a little timid but every day she becomes more brave. She is playful, full of fun and great company,” writes Campbell. “She did remove all obstacles to my physical, emotional and mental health.”

Another uplifting essay is the one on how Campbell has “never come of age.” When she paints and creates with friends, she feels like she is 5 years old, she says. When with her teenage grandson, she also feels like a teen, and sees “the wonder of the world.”

Campbell has role models, older friends and neighbours who still have bucket lists and exercise regimes. Having traveled much herself – Myanmar, Morocco, Vietnam, India, Cambodia, Laos, Turkey and other places – she now wants “to do inward travel. To get to know myself and others around me. To find the mystery inside. To nourish relationships with the people I know and with new people that I meet.” She wants to have different adventures: “Creative adventures, people adventures, spiritual adventures.”

There are more than a dozen recipes in Dear Arlo – from an apple torte that a 5-year-old Arlo bet Campbell she wouldn’t make (which she did but he never ate); to cabbage pie and Russian salad, recalling when Arlo was teaching himself Russian; to broccoli and cheese soup, vegetarian meatloaf and ginger apple tea, in response to Arlo’s request for some recipes.

Campbell is grateful for many things.

“I have had a good marriage and a wonderful family – my lovely daughter, her loving partner and my wonderful grandson Arlo,” she writes.

“I have dealt with losses and tragedies in my life, including the premature death of my husband, but I survived, and now I am happy. Those intense feelings of sadness that I grew up with no longer plague me. I can be triggered, but on the whole, I am fine.”

The memoir ends as it begins, with a letter to Arlo, who, says Campbell, has been “the best grandson I could ever have imagined.”

She writes, “The past provides us with valuable lessons that we can use to inform our present and future. A sense of connection and continuity with the people who came before us. This adds a depth and richness to our lives. I look forward to having many more adventures with you.”

We get to see Arlo grow up, in photos throughout the book. And the photo placed squarely in the centre of this last letter is perfect: Arlo in the driver’s seat of his new red convertible, toque on, giving a thumbs up, smiling, with Campbell beside him, also bundled up for a cold drive, but also with a big smile.

To purchase Dear Arlo or Campbell’s previous books, visit olgacampbell.com.

Campbell’s artwork is on display at the Zack Gallery Jan. 8-27, with an artist reception Jan. 9, 6-8 p.m. Campbell speaks as part of the JCC Jewish Book Festival on Jan. 23, 7 p.m., in the gallery.