Hüttenbach in Medan in 1880s. (photo from KITLV Album Or. 27.377)

Jewish communities in Indonesia have always been tiny, though their history is long. Jewish merchants are recorded in Sumatra as early as the 10th century, and diasporic and Israeli newspapers regularly report on the very small groups of Jews now living in Indonesia. (A 2022 article estimated that there were only 50 Indonesian Jews, and perhaps 500 Jewish expatriates.) However, the largest communities with the most substantial record are those in the late colonial cities of Batavia (now Jakarta), Surabaya and Manado.

The digitization of Dutch archives, both from European publications and the colonial newspapers, has facilitated research about the history of Jewish groups in the Indonesian archipelago. In this article, we offer some notes towards a history of some Jewish merchants in Medan between the 1870s and 1940s, as tobacco plantations on Sumatra’s east coast developed.

The Deli region on the east coast of Sumatra was not developed until the mid-1860s, when a few Dutchmen accepted an invitation from the sultan of Deli to establish tobacco plantations in the area. By the late 1890s, it had become one of the most profitable parts of the Dutch empire.

Deli tobacco leaves were “thinner than cigarette paper, and softer than silk,” and quickly the plantation zone’s tobacco became highly valued. The result was a brown “gold rush” of Deli tobacco in the late 1870s, attracting German, Swiss, English and Polish planters, as well as Dutch, to the new “dollar land.” Planters, tolerated and sometimes abetted by colonial authorities, instituted a brutal and often murderous system of exploitation of imported Chinese and Javanese labour.

Before long, merchants established themselves to serve the European population’s taste for European goods and technology. Among these new arrivals were several Jews, including Ashkenazi Jews from the Netherlands, Austria and Germany, as well as others who relocated from existing Baghdadi Jewish communities in Penang and Singapore. There are also scattered accounts of Jews in the Dutch army serving in Sumatra.

Mercantile opportunities

We know very little about how many Jews tried their luck in the eastern coast of Sumatra, but we have not yet found any evidence of a synagogue (as in Surabaya) or a dedicated cemetery (as in Aceh). The most consistent record of the community available today is not from the colony but rather from Amsterdam’s Nieuw Israëlietisch Weekblad (New Jewish Weekly). The first mention we have found in that newspaper was a report of an August 1879 anonymous donation of 60 guilders originating in the Sumatra’s east coast and destined for the Dutch branch of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, an international Jewish educational charity.

Between 1899 and 1901 the NIW published letters from N. Hirsch, a non-commissioned officer initially writing from the fortress of Fort de Kock (now Bukit Tinggi). In his letters, when not speculating that some Indonesians might be descendants of the lost tribes, Hirsch is troubled by the challenges of Jewish life in the Indies, without religious or community institutions. Months after his first letter, Hirsch joyfully reported the arrival of a kosher butcher and, in 1901, having since moved to Padang, on holding the first religious services at his home.

However, the bulk of sources concern a few European Jewish merchants who became prominent in Medan. Among the first Europeans to come to Deli were members of the Hüttenbach family, an established and assimilated merchant family from the German Rhineland city of Worms. The eldest son, August Hüttenbach, began working for the German-Jewish company Katz Brothers in Penang in 1872 at the age of 22. Katz Brothers, which had arrived in Penang in 1864 at the height of the tin rush, invested in all kinds of business, including supplying ships for freight. When the Dutch-Aceh war broke out in 1873, the company provided logistics and supplies to the Dutch military, and the Hüttenbach family’s shipping business ran a regular service to the Aceh ports.

While August became a prominent merchant in the British Straits settlement colony port of Penang (now in Malaysia), his younger brothers Jacob and Ludwig Hüttenbach settled across the Strait of Malacca, in Deli. In 1875, they opened the first European store in the harbour settlement of Labuhan Deli to cater to all the needs and requirements of the Dutch government, plantations and industrial groups.

Gradually, the family firm developed into a general merchandise company supplying all sorts of goods from Europe, and even establishing its headquarters in Amsterdam and another office in London. With their own shipping lines at their disposal, they were for a time the only importer in Deli. When the Hüttenbach enterprise moved its Sumatran operations inland to the developing city of Medan in the 1880s, the street on which they established their business was named Hüttenbach Street (today Jalan Ahmad Yani VII).

Hüttenbach enterprises supplied all manner of goods and services, ranging from live water buffalos and Brazil nuts to Bordeaux wines. It furnished machinery, tools, motors, electrical goods, harnesses, saddles, guns, ammunition, watches and clothing, and served as an agent for brands including Ford, Cadbury, Heineken and Guinness Stout, as well as other European trading, insurance and manufacturing companies. In the 1910s, its annual imports totalled 1,200,000 guilders and it supplied across the whole of Sumatra.

At the turn of the 20th century, Jacob and Ludwig retired to Europe and left Heinrich Hüttenbach (1859-1922), the youngest of the brothers, in charge of the company. Heinrich, who had been a well-known planter in Malaya, moved to Medan to run the company. A small glimpse of the brutality of plantation life is visible in the German primer Heinrich wrote to provide instruction for Europeans learning plantation Malay (Anleitung zur Erlernung der Malayischen Sprache), including instructions such as: Lu orang bôhong. Lu bukan sakit. Lu malas sadja. Saja mau kassi pukul sama lu. (You are a liar. You are not sick. You are just lazy. I will hit you.)

Selling to the sultans

Medan’s growth attracted other Jewish merchants, who also opened stores selling European consumer items such as clothes and luxury goods. Two German Jews, Louis Kellermann of Leipzig and Max Goldenberg of Hamburg, opened the S. Katz & Co. shop in the Kesawan shopping street. The Katz Brothers, a prominent firm of Singapore and London, did not appreciate what appeared to be an appropriation of their name, and put a notice in the local newspaper, the Deli Courant, making clear that no connection existed. We cannot know whether Katz’s implication – that Kellermann and Goldenberg were seeking to capitalize on a familiar trading name for their profit – was correct.

Among S. Katz’s employees was Russian-born Alfred Aron Arnold Zeitlin (1863–1938). Partnering with Goldenberg, Zeitlin opened a new store called Goldenberg & Zeitlin in November 1898, on the same main shopping strip, Kesawan Street. Majestic by all accounts, they specialized in the importation on luxury items such as jewelry, music boxes, typewriters, hunting rifles, glassware, curtains, suitcases, cigars and so on.

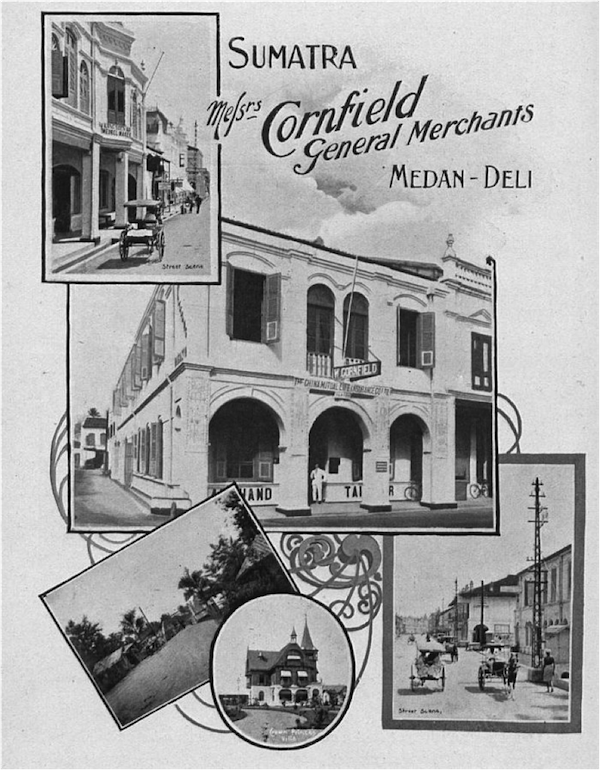

Other competitors were not far behind. An English-language travel guide to Sumatra in 1912 highlighted one of them: “A visit should also be paid to the establishment of Messrs. Cornfield. The firm are the official suppliers to the various sultans, and make a specialty of superior diamond jewelry of every description, although their stock includes well-selected continental fancy goods, pictures and also the latest modes.”

Wilhelm Cornfield (1862–1908), an Austrian Jew, had come to Deli in the 1880s, first working as a cutter at the S. Katz shop. In 1893, Cornfield started his own business as a tailor, offering European clothing with imported fabrics. Before long, he carried a complete range of clothes and luxury goods from London and Paris.

The first generations of merchants eventually left or passed away and were replaced by their children. When Wilhelm Cornfield passed away in 1908, his children expanded their father’s business. In particular, his son Isidore (1885-1923) became an investor in many luxury stores in North Sumatra, and also owned tea and coconut plantations on the east coast of Sumatra.

Heated competition

Jewish merchants competed to import European consumer goods, their firms merging, dividing and often clashing with one another. In 1915, the Hüttenbachs’ company split into a wholesaler business and the retail business. The retail business was managed by Isidore Cornfield while Heinrich Hüttenbach maintained the import interests. This split, however, caused a legal dispute between Hüttenbach and Cornfield about the management of the new department store. In the end, Cornfield won the case and opened Medan’s Warenhuis(Warehouse) in 1920, the first department store in Sumatra, the remains of which still stand. The Hüttenbach firm, on the other hand, was declared bankrupt in December 1921, after 46 years of business, due to the global financial crisis and mismanagement.

The bankruptcy resulted in Heinrich Hüttenbach’s return to Amsterdam. A few months later, he went missing on a passage from Amsterdam to London, and was declared dead five years later. The Cornfields, too, suffered great misfortune. Isidore and his wife, opera singer Henriette Zerkowitz, returned to Vienna, where he died of heart disease in October 1923 at the age of 38. By 1939, now run by his brother Adolf, the Cornfield fashion store, in financial trouble, was liquidated, closing its doors in July 1939 after more than 50 years of trading. Most likely, as the Depression caused a decline in demand for Sumatra tobacco, consumer luxury goods were no longer a viable business.

Like many other German and Dutch Jews, most of these merchants were assimilated to European society and identified with national groups in the colony. They belonged to Dutch and German clubs and contributed to patriotic celebrations. Indeed, Hirsch complained of the European Jewish merchants that they represented themselves as Christians, were lost in bitter competition with one another, and were utterly lacking in piety. With many secular and/or assimilated Jews, there seems to have been little impetus to form Jewish institutions.

Dutch Jews and war

At the end of the First World War, there was high demand for expatriates to come to the Deli region to manage plantations and serve the colony. Many Dutch Jews responded and went to work for plantations, Dutch companies or the government; there are also a few examples of Jewish doctors. But newspaper archives suggest that numbers remained tiny, and only from the mid-1920s is it possible to speak of community activities.

One tantalizing biography from the 1920s is that of writer, painter and planter László Székely, born to a Jewish family in what is now eastern Hungary, with a birth name given as László or Smiel Ziechrman. Arriving in Sumatra in 1914, his life and work is rather overshadowed by an affair with a Dutch planter’s wife, Madelon Lulofs, that scandalized Deli colonial society. After divorce and remarriage to Székely, Lulofs, in works such as Rubber (1931), became one of the principal literary voices critical of Dutch colonial power. Székely also wrote literary sketches of his own, mostly for the Hungarian press. His novel, translated into English as Tropic Fever: The Adventures of a Planter in Sumatra (1937), provides a candid picture of colonial planters’ life in Sumatra, now considered an important social commentary on that vanished society. The couple settled in Budapest in 1930.

When Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, the Jewish community raised funds to support relief efforts, but, by March 1942, Sumatra, too, had fallen to the Japanese. Some Jewish families found themselves under threat at both ends of the world: persecuted in Europe on the basis of their Jewish identity, and in the Indies as Dutch enemies of the Axis Japanese. Adolf Cornfield died in a Japanese internment camp. A Dutch Jewish physician who worked on the east coast of Sumatra, Dr. Hans Koperberg, was also captured and imprisoned by the Japanese. In a book of poetry titled Bittere pillen en scherpe pijlen (Bitter Pills and Sharp Arrows), he wrote about his experiences of being moved from one camp to another, dedicating his book “to my two sisters murdered by the Huns, Uncle Dr. Felix Catz and Aunt Brama and to all the friends murdered by the Japs.”

Our investigations have so far found little record of Jews in Sumatra after the Second World War. Survivors left for the Netherlands or perhaps Australia and, by 1958, Sukarno had expelled all Dutch citizens from Indonesia.

Budiman Minasny is a professor of soil landscape modeling at the University of Sydney with an interest in Indonesia colonial history. Josh Stenberg is a senior lecturer in Chinese studies at the University of Sydney. An earlier version of this article was published in Inside Indonesia 146: Oct-Dec 2021.