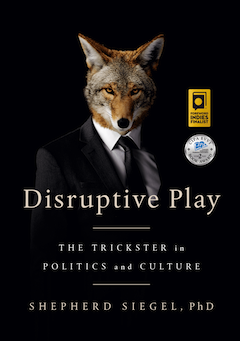

“We are Family” by Cat L’Hirondelle is now on exhibit at the Zack Gallery, as part of he group show Community Longing and Belonging, which runs to March 29.

The new group show at the Zack Gallery, Community Longing and Belonging, is the second annual exhibit in celebration of Jewish Disability Awareness, Acceptance and Inclusion Month. Organized by Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver’s inclusion services and its coordinator, Leamore Cohen, the show is a silent auction. Half of the proceeds will go to the artists, and the other half will be divided between inclusion services and the gallery.

The show consists of 50 paintings by different artists. The size and shape of all the paintings are the same – small rectangles – but the contents and media used are vastly different, indicative of the artists’ various styles and training levels. Some are highly professional. Some are figurative; others abstract. But all reflect their creators’ need to belong, to be part of a community. Each painting tells a story.

One of the prevalent themes of the show is flight. Wings appear on several paintings, emphasizing the yearning for the freedom flight entails, but also for the brotherhood of other fliers. The white ornamental wings on Mikaela Zitron’s multimedia piece are bigger than the background board. They take the artist into the sky, into a joyful aerial dance, while Jamie Drie’s feathers, drifting in a sad emptiness, invoke the feeling of disconnection.

The murder of crows in Cat L’Hirondelle’s painting relates yet a different story. “I am a feminist,” said L’Hirondelle. “I was thinking about the importance of being part of a community of like-minded women. My group of longtime women friends is my family, my tribe and, like the crows, I know that they will always be there for me. Since I became disabled, I have felt more and more disassociated with the able-bodied-centric society in general. Just look at the history of people with disabilities in different societies – genocide, forced sterilizations, segregation, isolation, etc. I would love to feel that people with disabilities belong in the world. My piece is trying to impart that sense of longing to be included in general community and how crow communities seem to include everyone: the old, the disabled, the young. I have lived in the crow flight path for many years and have been watching crows’ behaviour; sometimes, I wished people were more like crows.”

The second recurring motif in the show is loneliness, the sense of separation. Daniel Malenica’s image is distinctive among such pictures. The woman in the painting stands behind closed garden gates. She gazes at us from the painting, and the naked longing in her eyes is painful to behold. She desperately wants to open that gate and step through, to join us, but she lacks the courage. What if the people inside reject her? So, she just lingers outside, desolate and alone, waiting for an invitation.

Another outstanding piece on the same theme is Estelle Liebenberg’s black and white painting “Solitude Standing.” She told the Independent, “I work primarily as a potter and a metalsmith, but I accepted the challenge to paint something for the exhibition because I’ve had wonderful times working as a substitute art instructor at the JCC. I chose the monochromatic colour palette because, at the moment, I am quite fascinated by shadows, specifically how they change the shape of objects but still remain recognizable.”

Her focus for the piece was the idea of a community in general. “I’ve spent my life dealing with different communities and, I guess, for me, the lines have softened over time,” she said. “We spend so much time in our lives working on belonging, or longing to belong somewhere, to someone or something. It’s an integral part of the beauty, the joy, the frustration and the heartbreak of life. For me, this was longing and belonging as an immigrant, as an introvert, as a mother of grown children, as a single person living in a city.”

She explained the title of her painting: “It is a hat tip to a song by Suzanne Vega. For me, her words truly encapsulate the feeling of longing to belong somewhere: ‘Solitude stands in the doorway / And I’m struck once again by her black silhouette / By her long cool stare and her silence / I suddenly remember each time we’ve met.’”

Different artists explore different aspects of community and belonging, and not all the communities are small or local. For Marcie Levitt-Cooper, the community in her painting is the universe, the earth and stars encompassed by love. Esther Tennenhouse, on the other hand, contemplates the darker side of belonging.

“My piece is a photocopy from a pre-World War Two Jewish encyclopedia, Allgemeine Ensiklopedya,” Tennenhouse explained. “It was labeled in Yiddish and issued in New York in 1940, the year Germany occupied France. On first seeing this old map, I found it very poignant. The map had to fit the 16-by-16 canvas given to all participants. The format left space, and I filled it with the music of two nigguns and lyrics of six Yiddish songs.”

That colourful map with Hebrew lettering, published just before the Nazis unleashed the full horrors of the Holocaust on European Jews, made for a tragic, frightening image, despite its bright and cheery appearance.

While the exhibit includes other figurative paintings, the majority of the pictures are abstract, either simple swirls of paint or complex geometric patterns, like Daniel Wajsman’s piece – two irregular overlapping rectangles.

“I wanted to emphasize that we should bring everyone in, not leave anyone out,” he said.

Community Longing and Belonging runs to March 29.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected].