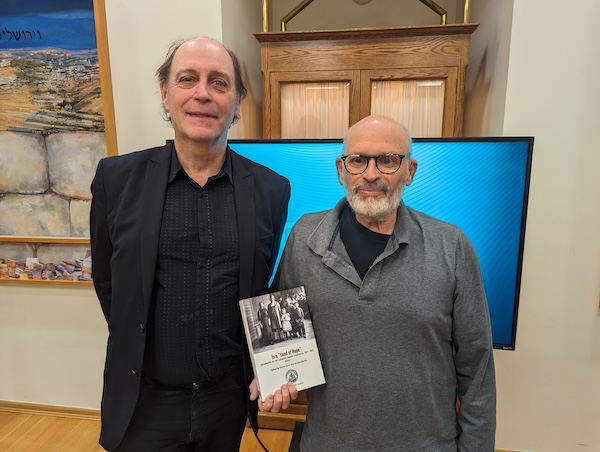

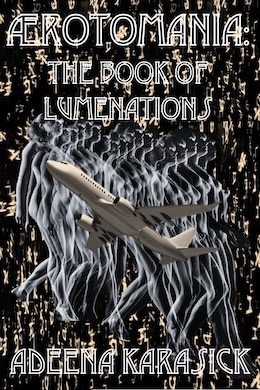

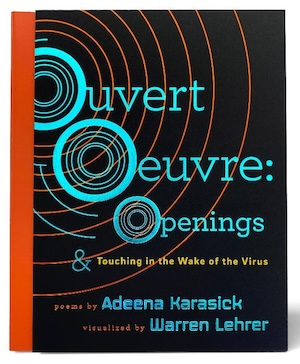

Inbal Ben Haim in Pli, which will be at the Vancouver Playhouse Feb. 2-3. (photo by Loic Nys)

Imagine flying through the air on … paper?! That’s just what the circus artists do in Pli, which is being co-presented by the PuSh and Chutzpah! festivals Feb. 2-3 at the Vancouver Playhouse.

The show’s concept came from Israeli French circus artist Inbal Ben Haim, who performs the work with Domitille Martin and Alvaro Valdes. Ben Haim has always been attracted to working with various materials. In her first show, Racine(s), which means “root(s)” in French, soil was used as “poetic matter to talk about the connection of human beings with the earth and [their] homeland,” Ben Haim told the Independent. Racine(s) premièred in 2018.

“But my story of paper started from a workshop I had while I was in CNAC [Centre national des arts du cirque], with the artist Johann Le Guillem. In the point of view of Johann, circus is a ‘minor practice’ – a practice that has never been made, that no one’s practising anymore, or that it is very rare. He asked us to prepare a small presentation … and I wanted to work with paper, to create a huge bird of paper and to fly on it. Well, I didn’t manage to do it, but I started sculpting the paper and made a paper puppet, which I suspended in the air and climbed on it.”

“A little bit later,” she continued, “I met Alexis Mérat, who is a paper artist [and who used to perform in Pli], and we figured out we do the same gesture with our hand – he is crumpling, and I am hanging from my rope. So, we wanted to try to do the two actions at the same time – to crumple and suspend. We were sure that the paper would break, but when we discovered that hanging from paper was possible, it inspired us a lot in the poetical point of view of this image – putting your body, your weight, your life, on something so fragile as paper. In a way, it’s a human action that we all do sometimes. It seemed to us that we absolutely needed to continue this research.”

As they did, Ben Haim said it became clear that they had to involve Martin, who she knew from Racine(s). Martin is not only a performer but a scenographer and one of Martin’s specialties is creating a set that is also circus apparatus, said Ben Haim. “This is how we started to work together.”

Ben Haim studied both visual arts and physical practice, and the visual circuses she creates are a melding of those two passions.

“I was always a hyperactive child,” she said. “I did sports, athletics and martial arts since [I was] very young. But, when I discovered circus practice, and especially aerial acrobatics, I found a space of quiet, of high intensity in a calm place. I found a different relation to gravity and to the body, and also a practice that was very physical but at the same time poetic and interior. It touched me deeply.”

Ben Haim said she wasn’t scared the first time she climbed a rope or was suspended from a trapeze. “I was used to climbing on very high places – trees, mountains, and so on,” she explained. “My parents tell that when I was 1 year old, they found me one day up on a ladder – which means I learned how to climb before I knew how to walk.”

It’s only as she has worked longer in the profession that she has felt more fear. “I get to be more aware of all the risks we take, not only in the acrobatic act but in the hanging and rigging – this is where most of the accidents happened,” she said. “I get to be more and more careful with age and with experience.”

Ben Haim moved to France in 2011 to pursue her art and training, first at Piste d’Azur: Centre régional des arts du cirque PACA, then the CNAC de Châlons-en-Champagne, from which she graduated in 2017. Her bio also notes that “she developed a teaching method for therapeutic circus and worked in various contexts in Israel and France. By blending circus, dance, theatre, improvisation and visual arts, Ben Haim has created her own form of poetic expression. Largely inspired by the human bond made possible by the stage, the ring and the street, she aims to create strong connections between the audience and the artist, the intimate and the spectacular, the earth and air, and the here and there.”

This interplay of connections is evident in Pli and how Ben Haim, Martin and Mérat worked together.

“In the moment we discovered that hanging and climbing on paper was possible, we dove into this research, and we wanted to discover and understand all the possible ways to do that,” said Ben Haim. “We did a lot of experiments which are visual and physical, but also mechanical. Alexis is an engineer, so he held all this point of view that finally makes all that we do quite safe.

“We were creating nine apparatus of hanging on paper in different ways, and we observed how the body changed the paper,” she continued. “We created also many scenographies from paper in which I entered to transform them, getting in a different relationship with the matter…. I metamorphose it, and then it holds me differently – it becomes a duet with lots of listening and care.

“In parallel, we were creating costumes from paper, we made lots of sound work, [registering] the different sonorities of paper to compose the music and doing … research on the possibilities of lighting paper on stage. We can say that the paper guided us in this journey.”

Jessica Mann Gutteridge, artistic managing director of the Chutzpah! Festival, was drawn to Pli right away when she was introduced to it by the PuSh Festival, whose director of programming is Gabrielle Martin.

“Chutzpah! and the PuSh Festival share many common interests in terms of the kind of work we present and have been looking for opportunities to work together,” said Gutteridge. “PuSh knows that Chutzpah! has a particular interest in presenting Israeli artists, as well as audiences who are interested in dance and innovative performance, so this project was an excellent opportunity for us to join forces and co-present.”

The 2023 Chutzpah! Festival, which took place just last month, “included a project that centred on long sheets of paper used to create visual artworks on scrolls, with professional and community artists exploring the centuries-old art form of crankies,” said Gutteridge. “This resonance with Inbal’s work creates a lovely bridge to our winter Chutzpah! PLUS collaboration with the PuSh Festival.” (Crankies are a centuries-old artform in which an illustrated scroll is wound on two spools set in a viewing window.)

Chutzpah! took place as the Israel-Hamas war continued, and the probability is that the war will still be going on when PuSh begins Jan. 18.

“We can say that art is not saving anyone’s life in times of war, so what is its power in front of violence?” responded Ben Haim when asked the role of the arts, even in times of conflict.

“I believe that art has the power to bypass the mind and touch beyond it – the heart, the emotions, the curiosity, our sense of humanity,” she said. “Art has the chance to connect us – above the definitions and identities, as nationality, history and politics. And can connect us into something bigger than what we think we are, something which is common.”

She said, “As someone who searches more for solutions than accusations in any conflict (personal or geopolitical), I search the space of connection moreover than the reasons of separation. I believe that that’s the only way we can find peaceful and respectful solutions for all sides. I feel the need of being able to deeply see each other, human beings, beyond the grief, the fear, the sadness. I think art offers us this kind of space, where we can feel all humans, and experience ourselves as a connected grid. It is not the ‘solution,’ but I think it’s a good starting point, especially in our days.”

Having lived for many years in Israel, in a region of recurring conflict, Ben Haim said, “I know how persistent experiences of fear, pain, loss and distress make us become less and less sensitive, and more into defensive and violence. It happens in order to protect ourselves from those difficult experiences, and it is common for all sides. But, in the long run, it is devastating, for ourselves and for our partners.

“Even in the middle of a storm of violence, I think art helps us keep a space of sensibility in this crazy world,” she said. “An untouched place where we can simply be, observe, experience, feel. To marvel in front of some piece of beauty, beside the destruction. Having, for short moments, a sense of hope. To feel the strength in the subtlety, in vulnerability, the power in the creative act, in being alive. And this sensibility can be a window of connection. A thread to follow slowly and gently.”

Pli is 60 minutes with no intermission and the teaser can be viewed on YouTube or Vimeo. It is recommended for ages 11+. For tickets to the Feb. 2-3 shows at the Playhouse (in-person and livestream), visit pushfestival.ca.