The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre maintains significant holdings of Nazi and antisemitic propaganda that bears witness to centuries of anti-Jewish hatred. Acquired through the generosity of local historians and collectors – Peter N. Moogk, professor emeritus, history, University of British Columbia; Kit Krieger, Joseph Tan, Harrison and Hilary Brown, and others – the propaganda in the VHEC collection promoted antisemitic stereotypes, including Nazi ideology, in Europe and North America from 1770 to the postwar period. Although the content is offensive, these primary sources serve as an important historical record of the “longest hatred.”

The study of propaganda is critical to Holocaust scholarship. Historic antisemitica reveals a cultural tradition in Europe that the Nazis were able to exploit in pursuit of their “Final Solution.” The stereotypes found in Nazi propaganda were hardly new; Nazi propaganda was built upon the same antisemitic rhetoric and tropes that had been repeated over centuries and across countries and continents. Viewed in this context, propaganda provides insight as to why the Nazis’ message met with little resistance from an audience familiar with the language and imagery of anti-Jewish hatred.

The study of propaganda is also important to our understanding of the use of a state’s authority to control targeted segments of its population. This dynamic is explored in the VHEC’s new exhibition, Age of Influence: Youth & Nazi Propaganda. Drawing upon diverse primary sources, Age of Influence examines the Nazis’ efforts to manipulate the experiences, attitudes and aspirations of German children and teens.

Many of the materials featured in this exhibition will be new to visitors, such as family photographs, Nazi youth magazines and anti-Roma youth fiction. Other artifacts will be instantly recognizable, like the infamous children’s books on display at the VHEC for the first time: The Poisonous Mushroom (Ernst Hiemer, Der Giftpilz, Nuremberg: Stürmerverlag, 1938) and Trust No Fox (Elvira Bauer, Trau keinem Fuchs auf grüner Heid und keinem Jud auf seinem Eid [Trust No Fox on his Green Heath and No Jew on his Oath], Nuremberg: Der Stürmer Verlag, 1936). Age of Influence is designed to encourage active engagement with these artifacts and images. Throughout the exhibition, questions prompt visitors to critically analyze materials on display and identify common techniques used to disseminate both positive and negative propaganda.

The exhibition’s storyline begins in the early 20th century, when youth in Germany started defining themselves as a distinct socio-cultural group, attracting the attention of parties across the political spectrum. Popularized by youth-led groups like the Wandervogel, the German youth movement sought independence from adult authority and embraced communal and back-to-nature ideals. Their activities focused on hiking, survival skills and group pursuits in nature. Against this backdrop, the Nazi party emerged and cast itself as the future-facing “movement of youth.” With its Hitler Youth organization, the Nazi party tapped into the German youth movement and set its sights on this demographic to shape the future of a “racially pure” and physically fit national community.

Age of Influence examines how the Hitler Youth became the regime’s most effective tool to indoctrinate children and teens in Nazi ideology. It offered German youth a powerful group identity and appealed to adolescent yearnings such as the desire to belong, the quest for action and adventure, a sense of purpose and independence from parents. With separate organizations for boys and girls, Hitler Youth glorified gender roles. Boys were prepared for military and leadership responsibilities while girls were groomed to become wives, mothers and caregivers for the nation.

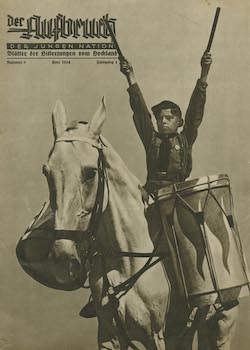

An array of Nazi youth magazines from 1934 to 1943 are featured in Age of Influence, as well as family photographs, collectible cigarette cards, video clips and Hitler Youth paraphernalia. Visitors can browse the pages of Nazi youth magazines to discover for themselves the eye-catching fonts, unique graphics and captivating images, which were carefully designed to attract young audiences. At its height, the Nazi youth press published 57 different magazine titles for children.

While participation in Hitler Youth was compulsory for most children, Jewish youths were banned from membership. Their experience is given voice in the exhibition by local survivors. In video testimony clips, Serge Vanry, Jannushka Jakoubovitch and Judith Eisinger describe their feelings of fear, shame and rejection as Jewish children confronted with pervasive antisemitic propaganda and excluded from the activities of their non-Jewish peers.

Perhaps the best-known propaganda tactic used by the Nazis was the creation of common enemies. Antisemitism and racism were key educational goals in the Nazi German school system, where students were taught that the health of the German nation was threatened by “inferior” groups like the Jews, Roma and individuals with disabilities. By demonizing and scapegoating these groups, the Nazis created a climate of hostility and indifference toward their treatment. Age of Influence depicts this process with reference to artifacts such as children’s books and instructional posters used in German schools.

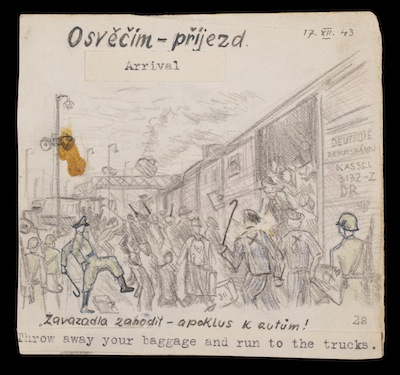

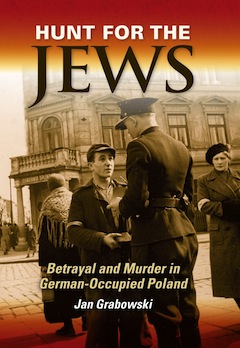

Contextualizing Nazi propaganda within a broad historical framework is essential. For this reason, Age of Influence has been mounted in conjunction with In Focus: The Holocaust through the VHEC Collection. In Focus presents a thematic history of the Holocaust, illustrated by artifacts donated to the VHEC by local survivors and collectors. A curated selection of antisemitica in this exhibition conveys the long-held perceptions and representations of Jews through time.

This history is also important as we navigate escalating antisemitism and racism around the globe and in Canada, where reports of antisemitic incidents have reached record levels. The use of digital media has amplified hate, and the ease with which disinformation can be spread on social media platforms perpetuates Holocaust distortion and denial. In this milieu, it is imperative to equip students with the media literacy skills required to critically evaluate information they encounter. Age of Influence will assist educators to promote key curricular objectives such as digital literacy, critical thinking and social responsibility.

For more information on Age of Influence and In Focus, visit vhec.org.

Lise Kirchner has worked with the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre since 1999 in the development and delivery of its educational programs. She was part of the exhibition team that developed Age of Influence: Youth & Nazi Propaganda, along with Tessa Coutu, Franziska Schurr and Illene Yu. This article was originally published in the VHEC’s Spring 2023 issue of Zachor.