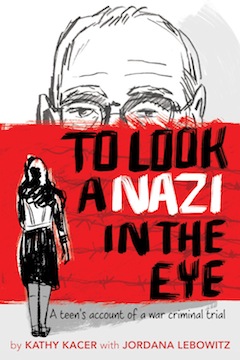

In spring 2015, at Luneburg Regional Court in Germany, the trial of Oskar Groening, “the bookkeeper of Auschwitz,” began. Nineteen-year-old Torontonian Jordana Lebowitz, a granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, was among those who witnessed the proceedings. The young adult book To Look a Nazi in the Eye: A Teen’s Account of a War Criminal Trial (Second Story Press, 2017), written with award-winning author Kathy Kacer, is about what Lebowitz experienced before, during and after the trial.

The book has different components and is not structured like a usual biography or historical account. It includes Lebowitz’s recollections as told to Kacer, as well as selections from Lebowitz’s blog, which the then-teen wrote for the Simon Wiesenthal Centre in Toronto about the trial. Numerous Holocaust survivors, now living in Canada, speak about their experiences at Auschwitz. They also traveled to Germany for Groening’s trial.

Lebowitz shares her concerns about going to Germany and readers learn how she made the trip come about. After almost every chapter, there are excerpts of Groening’s testimony that Kacer has based on news articles and interviews, as there were no transcripts from the trial itself. These sections allow readers to know what Groening was thinking as his claims were being assessed by the court. Charged with being complicit in the deaths of more than 300,000 Jews, he was eventually found guilty.

Lebowitz epitomizes how individuals from my generation should act. Her main goal was to ensure that the experiences of Holocaust survivors would be recorded so that future generations would be able to access them, and learn from them. Her main purpose in going to the trial was to witness this history and make sure that future generations would know it, too.

Lebowitz had been to Auschwitz on a March of the Living trip. The program takes students from around the world to Poland and Israel, so they can see firsthand and learn about the Jewish communities that once existed in Europe and the tragedy of the Holocaust that wiped almost all of them out. It was on March of the Living that Lebowitz met Holocaust survivor Hedy Bohm, with whom she became close friends. Bohm was imprisoned in Auschwitz for three months and testified in the trial against Groening.

As the bookkeeper at Auschwitz, Groening not only witnessed many Jews coming off the trains, but confiscated their possessions as they arrived. He was not tried for being a murderer, but for helping the Nazis murder Jews. The German government wanted Groening’s trial to occur, as they wanted Nazis who were still living to be brought to justice, even if it was many decades later.

Lebowitz heard about the trial from Bohm, and then set to figure out how she could attend it. The Simon Wiesenthal Centre agreed to fund the trip if she would blog her experience in the courtroom for others to read and follow as the trial was taking place. She managed to convince her parents she could handle what she would face on the trip during the trial, and Thomas Walther, the prosecutor, helped Lebowitz find a place to stay in Germany and procured a pass to allow her into the courtroom.

To Look a Nazi in the Eye is powerful in part because it reveals the compassion Lebowitz initially felt for Groening, in his frailty, sitting in the courtroom each day. He recounted heartbreaking stories of what had transpired in the camp. But, while Lebowitz believed at the start of the trial that he was truly sorry for what he had done, Groening’s stories began to change, and not for the better. He also said he was not guilty because he did not personally hurt or exterminate Jews.

To Look a Nazi in the Eye is powerful in part because it reveals the compassion Lebowitz initially felt for Groening, in his frailty, sitting in the courtroom each day. He recounted heartbreaking stories of what had transpired in the camp. But, while Lebowitz believed at the start of the trial that he was truly sorry for what he had done, Groening’s stories began to change, and not for the better. He also said he was not guilty because he did not personally hurt or exterminate Jews.

As her daily accounts progress, there are humourous moments that balance out the horrific stories about Auschwitz. For example, purses and paper were not permitted in the courtroom. In order to blog, however, Lebowitz needed a notepad and pen. So, she snuck toilet paper and a pen that was hidden in a place the security guards would not find during a body search. Her persistence paid off, and Lebowitz managed to take notes each day. That her family and others read her blog posts gave her some assurance that she was succeeding in her mission of helping keep the history alive and relevant.

One part of To Look a Nazi in the Eye that is amazing is how Lebowitz interacts with the Holocaust survivors. Bohm, Bill Glied and Max Eisen were among the survivors who attended the trial and were brave enough to recount their experiences at Auschwitz. For them, and others, it was a duty to their family and themselves to ensure that some form of justice was achieved. At first, they seem pretty hesitant of a younger individual being at the trial, but later open up to Lebowitz more. Seeing a person from a younger generation advocating for this cause made them happy, in a sense.

Since returning to Canada, Lebowitz has remained involved in Holocaust remembrance. As the book’s website notes, she “came to understand that, by witnessing history, she gained the knowledge and legitimacy to be able to stand in the footsteps of the survivors who went before her and pass their history, her history, on to the next generation.”

Chloe Heuchert is a fifth-year history and political science student at Trinity Western University.

***

The following excerpt was published by CM: The Canadian Review of Materials and can be found, along with a review of To Look a Nazi in the Eye, at umanitoba.ca/cm/vol24/no2/tolookanaziintheeye.html:

“I wanted to leave,” replied Groening again in a voice that had grown increasingly hoarse. “I asked for a transfer to the front.”

Was it Jordana’s imagination or was Groening faltering under the strain of the trial and the intense cross-examination? She hadn’t noticed it before, but he looked decidedly weaker at this point in the proceedings than he had looked in the beginning. His face was haggard, his shoulders slumped, and his hands trembled.

Finally, Thomas [Walther] gathered his notes together and stood in the centre of the courtroom. “Behind me sit the survivors who are here to testify, along with their descendants,” he said. “I ask you, Herr Groening, did you ever think when you were in Auschwitz that the Jewish prisoners might stay alive and eventually have their own children?”

Groening shook his head and closed his eyes. When he finally responded, his voice was faint. “No. Jews did not get out of Auschwitz alive.”