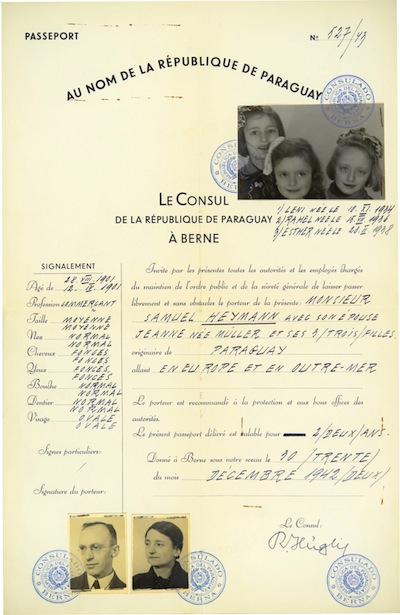

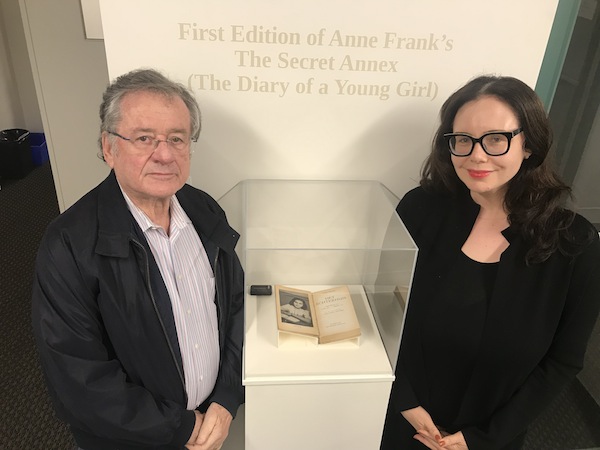

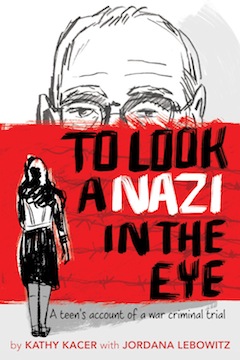

A scene from the documentary Martha, in which director Daniel Schubert is given a more appropriate shirt by his grandmother, Martha Katz. (Courtesy NFB)

Two very different scenes in the National Film Board of Canada’s short documentary film Martha – which will be released on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27 – combine to highlight the joy and pain that is life. Directed and co-written by Daniel Schubert, a grandson of the film’s subject, Martha Katz, there is a funny and relatable interaction where his grandmother questions his choice of shirt for the filming and provides him with a more appropriate one. This lighthearted exchange contrasts with the heart-wrenching tour that Katz takes with her grandson through the Holocaust Museum LA.

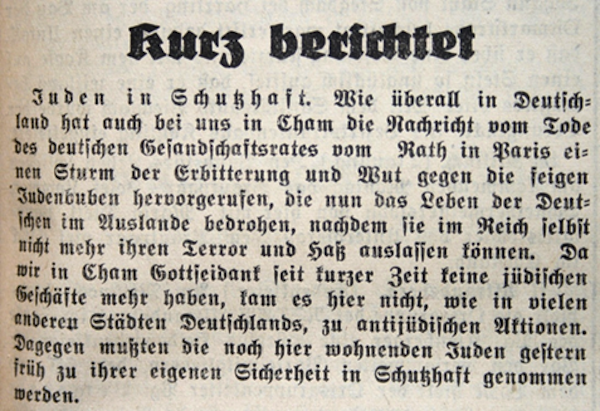

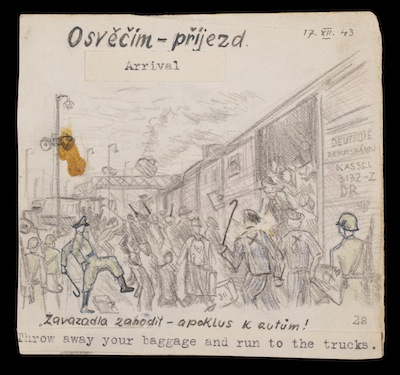

Born in Berehove, Czechoslovakia, Katz is 14 years old when she’s taken to the ghetto, then to Auschwitz. Both of her parents and two of her brothers were murdered in the Holocaust; she, along with two other brothers and two sisters, survived the concentration camps. She speaks, with emotions near the surface, about some of her experiences. The documentary is a mix of seemingly spontaneous moments, while other parts are scripted reenactments or prepared questions being asked and answered.

“My original idea for the documentary,” Schubert told the Independent, “was to track Martha and her two sisters’ incredible journey together through the ghettos and, eventually, Auschwitz. After Auschwitz, they were even forced to work at a German bomb factory together in Allendorf, manufacturing the bombs. The fact that Martha and her two sisters managed to stay together and survive through all of the horrors of the concentration camps, to me, was a miracle. I thought that would make an amazing documentary.

“But, as we developed it at the NFB, we realized that a more traditional cinéma vérité documentary could be a viable way to tell her story, too. I did not know many of the facts beforehand, so many of the things she told me in the film came as a surprise. My grandmother and I have a warm and loving relationship and I thought, why not show that on screen as I find out all of these amazing things?

“The other thing about my grandmother,” added Schubert, “is she’s hilarious. She’s the classic Jewish grandmother and I wanted that to come across. I wanted this to also be a real picture of a grandmother and her grandson and how we naturally interact.

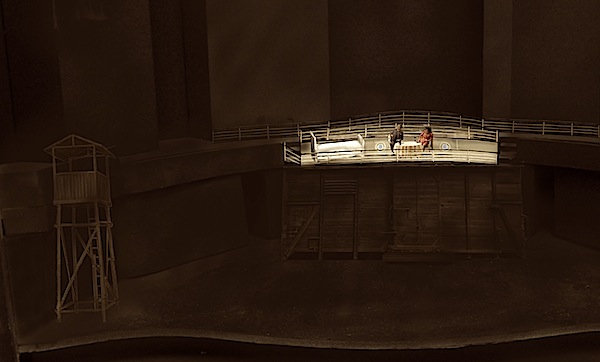

“We also decided that in between these cinéma vérité moments would be cinematic vignettes narrated by my grandmother herself. There were many more amazing things she went through, but, due to time constraints, I picked those stories.”

One of the stories is how, after the war, in Vienna, his grandmother met and married Bill Katz, who had been in a labour camp. The couple went to Winnipeg, with $200 they had saved up. They had two children – Jack and Sharon – and struggled financially. It was his grandmother who suggested they go into business for themselves. She went to night school, then saw an ad for a grocery store for sale – she bought it, learning on the job. There are some wonderful photos and video in this part of the film.

It was her goal in life for her two children to have whatever they wanted and she talks about her happiness at having had them. “We had to have a life again,” she says, stressing that this doesn’t mean she doesn’t think about the Holocaust all the time, because she does – “I hope it should never happen again. That’s all.”

“Bringing her to the museum was a bit of a tough decision, but she encouraged us to go,” said Schubert. “The intention was to see whether there was anything new that she and I could both learn about the atrocities committed. And, as it turned out in the film, there was; specifically, about the excruciating length of time the gas chamber took, in some cases, to exterminate those poor victims trapped inside, including my great-grandmother and her young son. Suffice to say, it took way longer than expected, and neither of us knew how long they may have had to suffer inside.”

It was for health reasons that Katz, who is now 90 years old, moved to Los Angeles.

“My grandmother suffered from chronic bronchitis since the war and, because of Winnipeg’s frigid winters, the doctors advised her to move somewhere warmer, or else her life could be at risk,” explained Schubert. “My grandfather’s brother lived in Los Angeles, so they helped them get settled there. They came to Winnipeg from Europe in 1948 and moved to Los Angeles in 1964.”

The 22-minute documentary is dedicated to the memory of Katz’s older sister, Rose Benovich. The statement at the film’s end notes: “Her courage in Auschwitz is the reason I am alive today.”