The following article was published in the Globe & Mail, as “A Dutch family hid me from the Nazis: I owe them my life,” in advance of Remembrance Day, Nov. 11, 2020. It is reprinted here with permission, in recognition of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27.

I can never pass Remembrance Day without reflection. This year, we marked the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Netherlands. It meant freedom for Dutch men, women and children after a brutal five-year occupation by German military forces. More than 5,000 Canadian soldiers rest in Dutch soil and are mourned and remembered there annually. They were our liberators and will never be forgotten, for Canadians and Canada are seared into the collective memory of the population. I myself saw Canadian tanks chasing German half-tracks down the streets of The Hague. On May 4, 1945, I was looking out the window of my mother’s small apartment, where she had been hiding. A man across the street opened his door one day too early. He was shot by a retreating German soldier. I was dragged away from the window. I was not yet 5 years old.

Unlike most Dutch children who began their lives anew after the war, I was a Jewish child hidden with Albert and Violette Munnik and their daughter, Nora, from November 1942 to May 1945. I became Robbie Munnik and was returned to my parents, who had miraculously survived, the only survivors of their families of origin. My grandparents, aunts, uncles and numerous cousins had all been murdered. For Jews, the postwar world offered precious little solace or hope: it was a world of death and of mourning. Liberation did not feel particularly liberating. Within that depressing atmosphere, I made the transition from Robbie Munnik back to Robbie Krell.

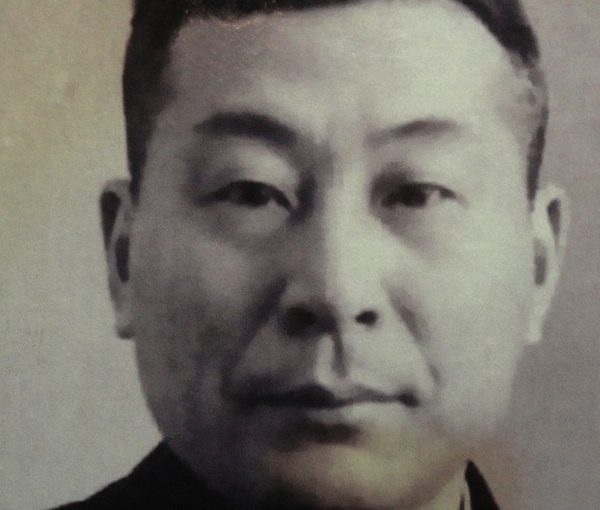

For this Remembrance Day 2020, I want to honour the memory of my Christian Vader, my second father.

When my mother passed me on to Moeder (Mother), who agreed to take me for a few weeks while she secured a hiding place, Vader accepted me without hesitation. Did he know of the risk to his family, hiding a Jewish child? If not in 1942, certainly he did by 1943. But, unlike many in this situation, he did not dwell on possible consequences. He simply set about loving me.

Early in my hiding, they allowed Nora to take me out, but that was a mistake. A woman recognized me. She happened to know my mother and asked Nora why she was looking after me. Vader contacted her immediately to ensure she remained silent. From then on, I was housebound. He read to me and made toys for me. His brothers and a sister all kept the secret of my presence. One slip could lead to betrayal. I was beyond lucky. Vader worked hard, loved deeply and enjoyed his hobbies, which included playing the piano by ear and carving wood and shaping metal. He was talented.

The danger increased. Only after the war would we learn that more than 80% of Dutch Jews were deported and murdered, primarily in Auschwitz and Sobibor. Of 108,000 souls sent to the death camps, only about 5,000 returned. And of about 14,000 children in hiding, more than half were betrayed, as was Anne Frank and her family in Amsterdam.

Because of his modest nature, Vader stands in danger of being forgotten. Of course, not by me. Unlike so many, including princes and popes, presidents and prime ministers, industrialists and intellectuals, he defied the Nazis and accepted the risk of my presence. So, while the names of the Nazis that murdered us linger on, as do the names of leaders who either did not lift a finger, or worse, actively prevented Jews from reaching safe havens, he might have been forgotten. So, I choose to remember him. In the hour of need, he included me in his life then and thereafter. His only reward was that I called him “Vader” and that he had, in addition to his daughter, a son.

In 1965, he and Moeder were brought to Vancouver by my parents to attend my graduation from medical school. My fellow graduates were drawn to him especially. He spoke no English, but the twinkle in his eyes spoke volumes. He was a people magnet. When they returned for my wedding in 1971, he fell ill shortly after and was briefly hospitalized at St. Vincent’s in Vancouver. There, he enchanted the nurses. When I came to visit, everyone on staff already knew him. They flocked to him. He radiated good humour and optimism. He did not know from anger, fear or bitterness. He hoped that I would not be consumed with anger over the Holocaust of my people, and that I would not turn away from Judaism or from Israel. And then, in 1972, he died. I do not know what he would have thought about the resurgence of antisemitism, the BDS movement and the antipathy toward Israel. But I can guess. And so can you.

But Vader will be remembered because Albert, Violette and Nora Munnik have been inscribed among “the Righteous” at Yad Vashem, the official site of Holocaust remembrance in Jerusalem. A tree planted as a seedling in 1981 grows at the site of the plaque bearing their names. And, in Vancouver, at Vancouver Talmud Torah Jewish day school, a sanctuary has been named in their memory and the entire story of their heroism lines the walls.

So, this year my memory is not consumed by what took place in Auschwitz and Sobibor, where so many of my family perished; this year, I will concentrate on remembering Albert Munnik, my Christian Vader, on Remembrance Day, and the Canadian troops that freed us.

Dr. Robert Krell is professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of British Columbia, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and founding president of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.