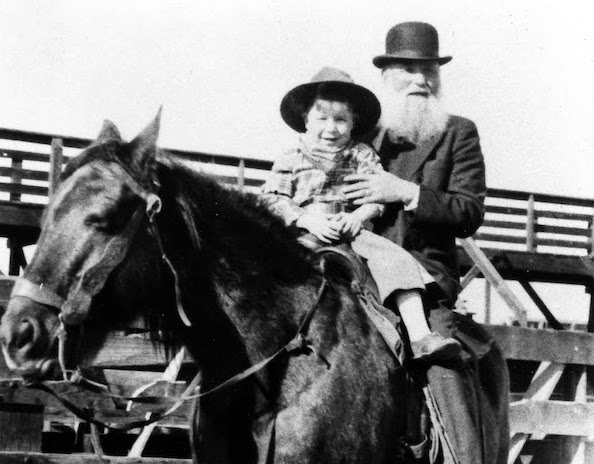

A still from Amanda Kinsey’s documentary Jews of the Wild West, a series of vignettes that shines a light on a noteworthy and usually overlooked history.

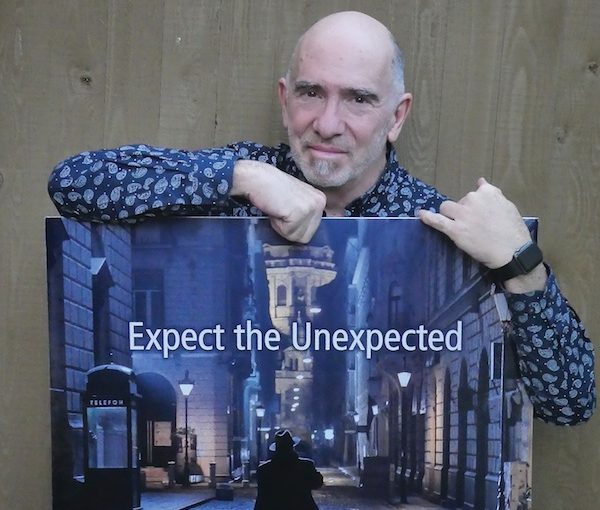

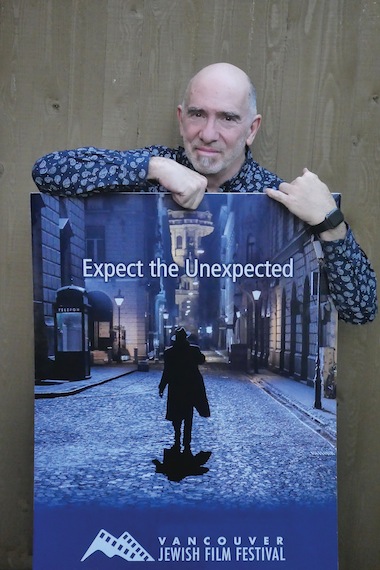

The Wild West, Jews in Germany and a surprisingly vivacious Israeli seniors home feature among the diverse films at the Vancouver Jewish Film Festival this year.

Somehow, we tend not to associate Jews with the legends that have built up around the development of the American West, a serious oversight that is in the crosshairs of filmmaker Amanda Kinsey’s documentary Jews of the Wild West.

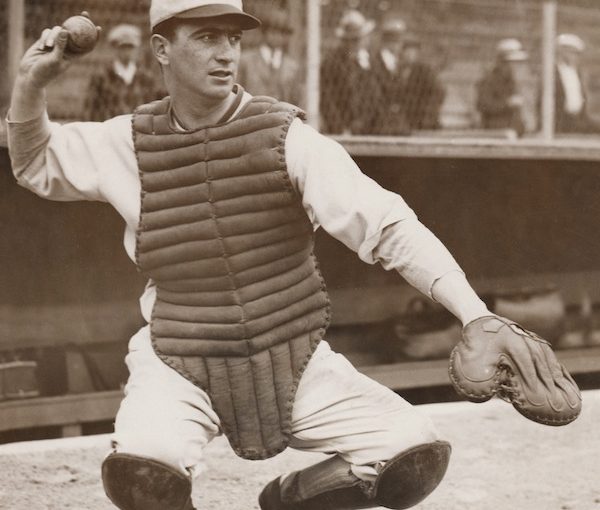

The mythology of the Wild West is perhaps as much an invention of Hollywood as of history, so it is notable that the 1903 film The Great Train Robbery, which introduced the genre of the cinematic Western, featured Gilbert “Broncho Billy” Anderson – né Max Aronson.

The myth of the West was no less inspiring to Jews than to other Americans and dreamers from around the world. Perhaps one of the most famous names in the lore was Wyatt Earp. The film introduces us to Josephine Marcus, who fled her family in San Francisco to become an actress and ended up being Earp’s wife. Earp himself is buried along with the Marcus family in a Jewish cemetery.

The gold rush drew Jewish peddlers and merchants to the West Coast in the late 19th century including, most famously, Levi Strauss, who left the Lower East Side and, via Panama, arrived in San Francisco. His brothers sent dry goods from New York and Levi sold them up and down the coast. When Jacob Davis, a tailor, was asked by a woman to construct pants that her husband wouldn’t burst out of, he imagined adding rivets. He took the idea to Strauss and the rest is American clothing history. As one historian notes, it was a Jew who invented “the most American of garments.”

The rapid industrialization in the mining sector is where the Guggenheim family got its start and so, while the name is now most associated with Fifth Avenue, the finest address in New York City, their start was in the gritty West of the 19th century.

We meet Ray Frank, the first woman said to have preached from a bimah. Called the “golden girl rabbi,” she was not ordained, but was apparently a phenomenon that drew crowds to her sermons.

Many people will know that Golda (Mabovitch/Meyerson) Meir spent formative years as an immigrant from Russia in Milwaukee and then Denver. This footnote to her history is often considered curious and interesting, but in this film it integrates the Jewish experience of the 20th century and its roots in the American West with the development of the Jewish state – the opening up of another frontier, one might say.

The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, seeing the poverty in the Lower East Side, actively encouraged migration to the West. The film introduces families who have worked the land for generations, some of whom have maintained their Jewish identity and at least one of whom was raised Methodist. But, it suggests, the thriving Jewish community of Denver owes much to the failed farmers of the West who made their way to the nearest metropolis to salvage their livelihoods.

The documentary is really a series of vignettes and at times the shift from one story to another is confusing but, as a whole, Jews of the Wild West successfully shines a light on a noteworthy and usually overlooked history.

* * *

The festival features two German films that complement each other in interesting ways.

In Masel Tov Cocktail, a short (about 30 minutes) film, high schooler Dima (Alexander Wertmann) welcomes viewers into his life just as he is suspended for a week as a result of punching a classmate in the face during an altercation in the washroom. The “victim,” Tobi (Mateo Wansing Lorrio), had taunted the Jewish Dima, graphically play-acting a victim in a gas chamber, a performance enhanced by the austere, sterile setting of the restroom’s porcelain-tiled walls. So begins an interplay of victim and perpetrator that is just one of several provocative themes weaving through this powerful short.

Dima’s family, it turns out, heralds from the former Soviet Union, like 90% of Jews in today’s Germany. After the fall of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany, the German government actively encouraged migration of Jews to revitalize Jewish life in the country. This fact, like other statistics and tidbits, is flashed across the screen.

Juxtapositions pack a punch, including Dima’s switching between a baseball cap and a kippa, perhaps reflecting his complex identities, as well as the schism in the identities of post-Holocaust Jews more broadly in a society that struggles to assimilate the idea of contemporary, living Jews in the context of the blood-soaked soil of their state. A shift from colour to black-and-white also evokes the stark break between the present and the past.

But the present and the past are themselves in conflict as Dima recounts how other Germans react when they learn he is Jewish. Why does he only meet Germans whose grandparents weren’t Nazis, he wonders. Statistic: a survey indicates that 29% of Germans think their ancestors helped Jews during the Holocaust, while the screen text helpfully informs us the number was more like 0.1%.

Dima’s teacher, who can’t utter the word Jew and struggles to get the word Shoah out of her mouth, wants Dima to share his family’s Holocaust story with the class. The film’s implication is that Dima’s family was largely spared the trauma of the Holocaust, but he decides to play along because, “There’s no business like Shoah business.”

Dima’s grandfather is taken in by the AfD, the neo-fascist Alternative for Germany party, convinced that their pro-Israel and anti-Muslim rhetoric means that they are defenders of the Jewish people. In a moment that confounds the AfD campaigner (and causes the viewer to reflect), Dima drags his grandfather away from the campaigner while yelling: “Don’t let foreigners take away your antisemitism.”

The film is kooky, funny and light, while also serious, dark and thoughtful throughout.

That description applies to the similarly named feature film Love and Mazel Tov, which features Anne, a non-Jewish bookstore owner who has Munich’s largest selection of Jewish titles and who herself is more than a little obsessed with all things Jewish – including potential romantic partners.

“Some are into fat. Some are into thin. Anne is into Jews,” a friend explains. This turns out to be more than a romantic or erotic attraction, perhaps a disordered response to national and family histories.

Thinking she has found not only a Jewish boyfriend but a doctor at that, Anna (Verena Altenberger) courts Daniel (Maxim Mehmet), who in typical cinematic fashion lets her believe what she wants to believe until the inevitable mix-up explodes in a farcical emotional explosion – though not before an excruciating family dinner.

Parts of the film exist on a spectrum between cringey and hilarious. The film features (at least) two fake Jews who don this identity for extremely different reasons, inviting reflections on passing, appropriation and the fine line between veneration and fetishization.

Both of these films use humour to excavate deeply troubling concepts of identity and addressing horrors of the past. They approach these challenging themes in truly innovative and entertaining ways.

* * *

Understated comedy is key to the success of Greener Pastures, an Israeli film in which Dov, a retired postal worker, has lost his home after a “pension fiasco” involving the privatization of the postal service.

He is a curmudgeonly old square when it comes to marijuana, which the government has decided should be available to anyone 75 and over, but he sees a moneymaking opportunity. Dov (Shlomo Bar-Aba) enlists a network of seniors to order medicinal cannabis and mail it to him so he can distribute it to his “connection,” who shops it around to younger consumers. This “kosher kush,” guaranteed “Grade A government-approved stuff” sold in tahini bottles, brings Dov into conflict with a two-bit drug kingpin in a wheelchair and, of course, a snooping police officer.

There is romance and suspense in this madcap caper, but there is also the theme of elder empowerment, along with the laughs.

The Vancouver Jewish Film Festival runs online only March 3-13. For the full festival lineup and tickets, visit vjff.org.