Filmmaker Michelle Paymar. (photo from D-Facto Filmstudio)

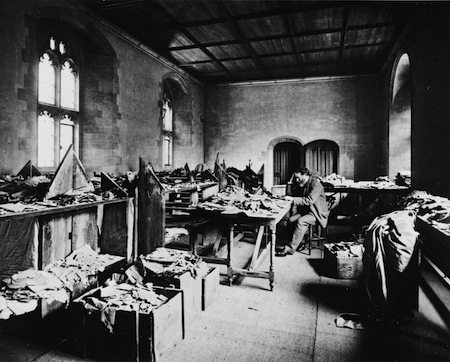

In the 19th century, the hunt for ancient manuscripts was in vogue, and a tip from two Scottish Presbyterian identical twin sisters – Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson – led talmudic scholar Solomon Schechter of Cambridge University to one of the most incredible discoveries. In 1896, he headed to Egypt, to Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, where he climbed through an opening high in a wall of the synagogue and found himself standing on countless documents that have “revolutionized our understanding of Jewish history.”

The documentary From Cairo to the Cloud, produced, directed and filmed by Vancouver-based filmmaker Michelle Paymar, chronicles the history of the search for the Cairo geniza, or storeroom, which contained more than 900 years’ worth of material – more than half a million fragments. There were religious texts, personal letters, bills, bureaucratic

reports, a child’s practise of the alphabet, artwork, prescriptions, what someone had for lunch and even handwritten drafts penned by 12th-century rabbi and physician Moses Maimonides. The geniza contained a written record of almost every aspect of Jewish life, in multiple languages: Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, Judeo-Greek, Judeo-Spanish, Judeo-Persian and Yiddish.

From Cairo to the Cloud sees its North American première at the Vancouver Jewish Film Festival on Nov. 12, 3:30 p.m., at Fifth Avenue Cinemas. It had its world première at the Cambridge Film Festival earlier this week.

“Many years ago, I learned about the existence of an archive that was essentially a time capsule of Jewish life in medieval Egypt,” Paymar told the Independent. “Then, in 2011, two books about the Cairo geniza appeared – one by Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole called Sacred Trash and one by Mark Glickman entitled Sacred Treasure.

“I was captivated by the immediacy of the voices from the geniza, the richness of Judeo-Arabic culture, and the sophistication of their milieu. When I learned that Cambridge was in the process of digitizing its final geniza documents for the Friedberg Genizah Project, I called Ben Outhwaite, the head of the geniza collection at the Cambridge University Library, to find out if any film crews would be documenting this momentous event. No one was planning to film the digitization of the last documents, so I grabbed my camera and my gear and went to Cambridge to film it myself.”

Using narrations of various texts (translated into English), archival images, animation, visual effects and lots and lots of interviews, From Cairo to the Cloud does indeed take viewers from Cairo to the Cloud, or the internet. Thanks to the Friedberg Genizah Project, all the geniza fragments are now accessible by researchers around the world. With the physical manuscript pieces stored in different institutions, it used to be that, to study one document, a researcher might have to go to several cities just to puzzle together part of a page. Not only is that travel no longer necessary but, because every scribe writes in a unique way, computer programs have been able to match texts using a technology like that which is used in facial recognition, making it possible to join hundreds of pieces of a document within a couple of months.

Wherever you have a Jewish community, you must have a geniza, explains Prof. Hassan Khalilieh (University of Haifa) in the film. Rabbi and author Mark Glickman then explains that a geniza is a place to store damaged Jewish religious texts and documents. Geniza is a Hebrew word for hide, adds Prof. Yaacov Choueka (Friedberg Genizah Project). In Jewish law, he explains, you are not allowed to destroy or deal disrespectfully with written material with God’s name on it.

So, continues Prof. Janet Soskice (University of Cambridge), that document has to be treated with the reverence you would accord to a human body. Once a home’s or synagogue’s geniza is full, the stored material gets taken to the cemetery and buried. But, what author Dara Horn notes is that the Jews of medieval Cairo had a different method – they not only saved documents with God’s name in it but any document written in Hebrew letters, and they didn’t empty their geniza for more than 900 years.

Quick snippets of information from academics, librarians, writers and other experts keep From Cairo to the Cloud moving at a good pace, while not losing its educational aspect.

“I started with a few names and those names begat more names,” said Paymar. “I soon discovered that these ‘geniziologists’ were wonderful storytellers and passionate about the geniza. I ended up interviewing about 40 people representing a wide range of interests and three generations of geniza scholarship. The oldest – Mordechai Friedman, Avraham Udovitch and Mark Cohen – studied with [ethnographer] S.D. Goitein himself. Then there are the students of Goitein’s students, like Marina Rustow, and her student, Arnold Franklin.

“I have about 60 hours of interview material. Once I started piecing together the story, it became more or less clear which selections to use from each of the interviews.”

And what a story it is, between how the geniza was found – meeting people like the sisters Smith Lewis and Dunlop Gibson, who were academics in all but name, knowing 14 languages between them and taking multi-continent excursions, often in search of ancient manuscripts – and the documents from the geniza itself. The material in the storeroom roughly covers the period 1000 to 1250 in Fustat, which started as a separate city than Cairo, and was a major hub for trade.

“Gaining permission to film in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo,” explains Paymar in her director’s notes, “required nearly seven years, three Egyptian governments, gaining the support of representatives from the Jewish community of Cairo, the assistance of the Canadian consulate in Cairo, approval by the Egyptian ministries of the interior and antiquities, the Egyptian state police, the Egyptian tourist police, the Egyptian Press Office and the Jewish community of Cairo. I was the first filmmaker in decades to be allowed to film inside the synagogue.”

Because of Paymar’s efforts, the rest of us can see inside the Cairo geniza’s treasures much more easily. We should take the opportunity to do so. It is a fascinating journey.

For the full Vancouver Jewish Film Festival lineup, visit vjff.org.