The rich and rugged history of Jews in the Yukon has found an internet home on the website of the Jewish Cultural Society of Yukon, jcsy.org. The lure of the Klondike Gold Rush and the stories of its enterprising and colourful Jewish personalities, some respectable and others salacious, comprise a large portion of the newly created virtual real estate.

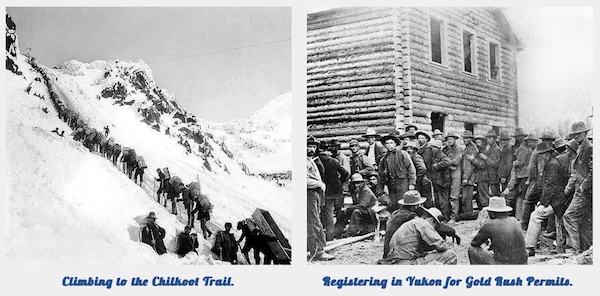

The quest to get to the gold, a journey undertaken by 100,000 prospectors between 1896 to 1899, was treacherous, the site explains. There were several routes, but one of the more popular ones was boarding a ship to Skagway, Alaska, then trekking over the Chilkoot Trail to Yukon. Once there, prospectors and retailers set out along Yukon River for another 550 kilometres to Dawson City – a trip that could take months – traveling during the winter so they would be ready for the summer prospecting season.

Prior to venturing on their northbound journey, however, fortune seekers needed supplies, dubbed a “Yukon Outfit,” the equivalent of one ton of provisions, which were essential to live and work in the north. The website shows photos of people bearing heavy loads headed to Dawson City, climbing ice-carved stairs to get to the Chilkoot Trail.

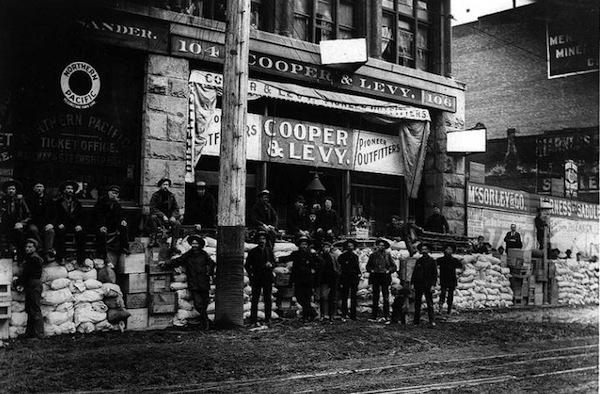

On the same page, there is a newspaper ad by Cooper & Levy, a Seattle company equipping gold hunters for their excursions. “Are you going to the Alaska gold fields? If so, send for our Supply List for ‘One Man for One Year’…. The list will be sent free of charge to any part of the world,” the ad reads.

“The idea of getting to Dawson City was an unbelievably difficult task. People needed to get there on a raft with all their things. The strength of the people was incredible,” said Rick Karp, president of the Jewish Cultural Society of Yukon (JCSY). “It was not a party. It was unbelievably difficult and many didn’t survive. As well, the First Nations communities suffered life-changing events.”

Albert and Marcus Meyer, whose histories are told on the website, were but two of the many industrious Jews to land in Dawson City. They opened a jewelry business in 1897, were buyers of Indigenous gold and produced Indigenous-style gold jewelry. Expert silversmiths, they also crafted silver trade bracelets with carved Tlingit designs.

Other families with connections to the Klondike would rise to prominence elsewhere, such as the Barrons in Calgary and the Oppenheimers in Vancouver. And there is Sid Grauman, whose father wanted to build a theatre in the north, and who would later establish the famed Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles.

Diamond Tooth Lil, on the other hand, was one of the notorious characters to arrive north of the 60th parallel. Born Honora Ornstein, she started out as a star “entertainer,” popular among spendthrift gold seekers and purportedly owned a luxury home in Skagway that “catered” to wealthy clients.

Another page of the website includes photos and video footage of the discovery, restoration and rededication ceremony of the Jewish cemetery in Dawson City in 1998. Herb Gray, deputy prime minister of Canada at the time, made a speech at the ceremony.

The JCSY has plans to expand the website in the coming months. “We will be keeping the site up to date and will be posting more information and photos,” Karp said.

The JCSY has plans to expand the website in the coming months. “We will be keeping the site up to date and will be posting more information and photos,” Karp said.

Originally formed as the Jewish Historical Society of Yukon in 1997 after the discovery of the Jewish cemetery in Dawson City – a century after the Gold Rush – its mandate was to clean, restore and rededicate the cemetery, as well as research those buried there. The identification of those interred inevitably led to questions about the others who participated in the Gold Rush, what they did during their stay, and the impact they had when moving on to other communities or returning to the families they’d left behind in search of fortune.

Upon completion of the cemetery project, the historical society believed its work was complete. However, by 2012, with the growth of the Jewish community in Whitehorse, interest in their work flourished and the JCSY was formed. Its mandate expanded to include forming a community to share Jewish culture, celebrate the High Holidays and Passover together and hold social gatherings.

The stories the society uncovered in its goal to learn more about the Jews of the Gold Rush resulted in the creation of a traveling historical display to share them. The display was exhibited both in Vancouver and on Vancouver Island, last making a stop at the Jewish Community Centre of Victoria in 2020. (See jewishindependent.ca/victoria-hosts-klondike.)

One can become a member of the JCSY through the website. The cost is $25 for a single membership and $40 for a family. Should a person make a donation of any size to the JCSY, they will be sent an email with a link to a new booklet (upon its completion), which outlines many of the notable stories of the Jewish presence in Yukon during and after the Gold Rush.

A section of the booklet’s introduction states, “While the north may not seem like an obvious choice for a nice Jewish boy from Milwaukee, Edmonton, Vancouver or Seattle, when you think about it, it is not such a stretch. Harsh times foster resilience and for every dreamer there is also a pragmatist. With a history of harsh times, Jewish people have been nothing if not resilient.”

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.