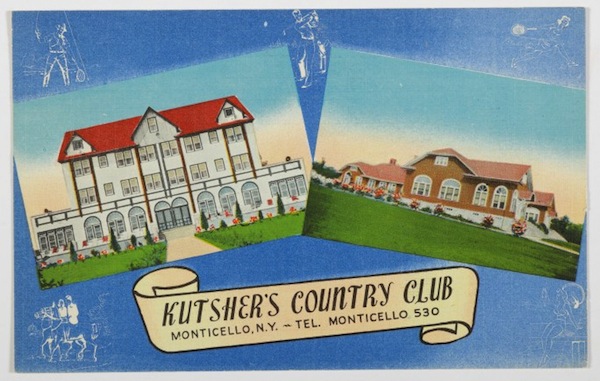

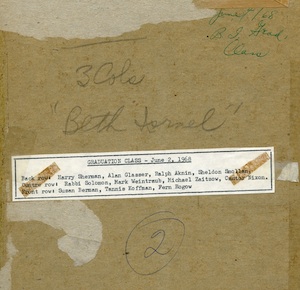

The new Beth Israel building welcomes people from 28th Avenue, while the original building (below) had its entrance on Oak Street. (photos from Beth Israel)

Congregation Beth Israel celebrates its 90th anniversary with a gala on June 12. It will feature “a walk down memory lane through each of the past nine decades,” as well as music, cocktails, dinner and other activities.

While the congregation’s history began in the 1920s, it wasn’t formally established until 1932. In a feature article in The Scribe (2008), community historian Cyril Leonoff, z”l, quotes an Oct. 9, 1931, editorial in the Jewish Western Bulletin, the predecessor of the Jewish Independent. A meeting had been held at the Jewish Community Centre, which was at Oak Street and 11th Avenue in those years, to discuss the possibility of a new congregation. The editorial commented:

“There can be no doubt in the minds of anyone that there is a distinct need for a Conservative or semi-Reform congregation in Vancouver. There are hundreds of Jews and Jewesses and their children who are so far removed by environment and training from the strictly Orthodox service that they have no inclination or desire to attend the synagogue now in existence here. The absence of [such a] synagogue carrying the services at least partly in English, has created a void in the religious life of many of our Jewish people…. The consensus of opinion in the community is … that a new congregation will be welcomed.”

The Jewish Community Centre was considered the best location initially, as the synagogue’s founding was during the Great Depression. Leonoff again cites that Oct. 9, 1931, editorial: “That the Community Centre, situated, as it is, convenient to all residential districts, would be the ideal place in which to set up the new congregation until such time as there are sufficient funds available for the erection of a separate building.”

It wasn’t until the end of the Second World War that the land along Oak Street between 27th and 28th avenues – where the synagogue still stands – was bought. As Beth Israel’s website notes, “by the late 1940s, both a rabbi (David Kogan) and a building site – at 27th and Oak – became available and, in 1949, Beth Israel’s synagogue was dedicated.”

The congregation grew over the years and, for three of those first several decades, the synagogue was led by Rabbi Wilfred and Rebbetzin Phyllis Solomon, Cantor Murray Nixon, z”l, and Ba’al Tefillah, Torah reader and teacher David Rubin z”l.

Programs increased, as did the participation of women, beyond a bat mitzvah ceremony. According to the BI website, “In the late 1980s, it became clear that women, now well-educated in Jewish ritual and study, were ready to move up to the bimah and take their place as full participants in synagogue ritual. By 1989, women were called to the Torah for their own aliyot, were counted in the minyan and acted as sh’lichat tzibbur (prayer leader). Beth Israel was the first major Canadian Conservative congregation to become fully egalitarian.”

The synagogue’s current senior spiritual leader, Rabbi Jonathan Infeld, and his wife Lissa Weinberger came to Beth Israel in 2006 via Ohev Shalom Synagogue in Marlboro, N.J. He told the Independent at the time: “We are very excited about moving to Vancouver, taking on an exciting challenge and being part of this community. I didn’t really know much about Beth Israel when we visited Vancouver, but after doing some research, I realized what a wonderful synagogue with a rich history it was.”

“It has been a pleasure working with Beth Israel as its rabbi for almost 17 years,” Infeld told the JI last week. “I remember the first day I walked into the synagogue. The congregants were wonderful. They were kind and welcoming. But the building was dated and literally falling apart. Everyone knew that we needed a new space for our spiritual home. After a few years, we were able to build an incredible and beautiful new synagogue that will last us for generations. We built a synagogue building for a new millennium…. Beth Israel has always been at the heart of the Vancouver’s Jewish community. I am proud to be part of that. I am sure that the spirit of Beth Israel will be strong for at least another 90 years. I look forward to helping to nurture it for many years to come.”

Construction on the current building began in 2012 and it was dedicated in September two years later. Along with Infeld, Beth Israel is currently led by Rabbi Adam Stein, Ba’alat Tefillah Debby Fenson and youth director Rabbi David Bluman.

“According to Mishna Pirkei Avot,” said Infeld, “a person is strong at the age of 80 and bent over at the age of 90. Beth Israel certainly has shown that 90 is the new 80. We are stronger than we have ever been. We are a synagogue built on the shoulders of giants. Many great women and men have dedicated their time, sweat and tears into building Beth Israel to be the synagogue that we are today. We greatly appreciate that. We could not be where we are today if it were not for them. And we greatly appreciate all of the people who continue to support us so that we can continue to grow and serve the Vancouver Jewish community. Ninety years is a big milestone in the life of synagogue. We really look forward to celebrating our 100th anniversary in 10 years.”

The 90th anniversary gala chair is Dale Porte and committee members are Howard Blank, Alexis Doctor, Jean Gerber, Myrna Koffman, Debby Koffman, Alan Kwinter, Debbie Setton, Leatt Vinegar and David Woogman. To purchase tickets to the June 12 celebration, call the synagogue office at 604-731-4161 or visit bethisrael.ca.