Before the pandemic, we were once at synagogue on Shabbat when the clergy person leading the family service reminded us that, hey, Elul was here, and we could hear the shofar blown if we came to morning minyan. The next day, Sunday, one of my kids decided we needed to go hear the shofar. It was just a normal Sunday. The minyan was small, largely comprised of senior citizens. My elementary school-aged kid rocked and wiggled in his seat. Most of the adults there smiled and gave him high fives and handshakes and made him feel welcome.

When I explained our shofar mission, they nodded. They all understood why we were there. My kid was given honours and made to feel special. When it was time to hear the shofar, he sat up and listened intently. It was one of those times when I thought, “Oh, we should try to come to minyan to hear this every day.”

This was one of those moments when my aspirations were much higher than my capabilities. Years later, I can’t pretend we’ve ever made it to morning minyan regularly again, even virtually, even during Elul. Maybe, someday, I’ll be one of those senior citizens in the frequent minyan attendee club. For now, I’m rushing to get everyone up, fed and out the door to school and work.

Still, I think that morning minyan experience may stick in a kid’s mind. The Elul shofar is a quintessential wake-up sound for many Jews. It’s the time to think about how the year has gone. We can focus on what’s ahead on the Jewish calendar, how we can make amends and do better in the future. What will change next year? What, most likely, will stay the same?

Is this wake-up ritual true of everyone? No, of course not. I recently saw a TikTok reel of a man, probably in his 20s or early 30s, with a beard. The guy was joking that he observed Jewish holidays through food, and then jokingly said, “Rosh Hashanah? That’s the one with the matzo balls, right?” Maybe I haven’t remembered the skit’s details quite right, but I wasn’t its intended audience. I inadvertently cringed. It was grating to me, jarring, like driving the wrong way down a one-way street.

Here was this guy, probably an influencer, showing everyone that he not only wasn’t religiously literate, but also thought Ashkenazi food was the only essential part of the ritual or the holiday. I mean, food is part of Jewish ritual, don’t get me wrong, but, it rubbed me the wrong way.

Here is a full-blown Jewish adult. And yet, he doesn’t think knowing anything about his ethno-religious identity or choosing to observe anything in regards to its religious context is his responsibility. As a Jewish woman who cares about this stuff, this irked me, because with his masculinity comes a lot of privilege in some parts of the Jewish world. He might be so privileged that he doesn’t even have to know any of this but he still would count in an Orthodox minyan and I don’t.

Our household philosophy is that, if people may potentially harass us or kill us for our Jewish identities, we should know more about who we are and why – and try to find joy or meaning in it. Focusing on Jewish knowledge and joy is kind of a “thing” for us.

This is when I have to remind myself, hey, it doesn’t matter how knowledgeable or observant or ignorant this guy on TikTok is. He’s still Jewish. I am no more or less Jewish than he is. It’s not a competition.

Elul is for introspection. It’s also the time to admit that we are all works in progress. I sure need to keep working. As we grow, learn and age, we can recognize and understand new and different things. Hardest, of course, is to recognize what we don’t know: our biases, intolerances and prejudices. We all have these blind spots. This emphasis, each year, on working on ourselves is valuable in many ways, not least of which is trying to be more inclusive and kind.

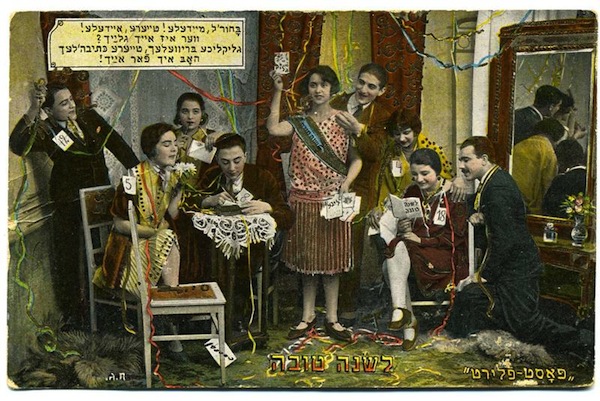

Elul is also about wonder – through our senses, when we hear, see, touch, smell and, yes, taste the holiday. It’s the primal feeling we get when hearing the shofar, or the release one gets after a heartfelt apology to a loved one. That wonder continues into Tishri, throwing our bread (like sins) in the water at Tashlich. The wonder is in sweet honey on apples and other holiday symbols. It’s in this season, in the northern hemisphere, when the days shorten and get cooler, the trees lose their leaves and we start again.

As I write this, it’s still summer. I’m the first to say that I’m not ready to embrace Elul. It’s coming though, no matter what. In preparation, we’ve already been apple picking at a neighbour’s tree. We got honey from a local farm. The food part is easy. It’s the introspection that’s the work – and I’m looking forward to hearing the shofar remind me to get busy doing it.

L’shanah tovah (Happy New Year) in advance. May the year ahead be sweet.

Joanne Seiff has written regularly for CBC Manitoba and various Jewish publications. She is the author of three books, including From the Outside In: Jewish Post Columns 2015-2016, a collection of essays available for digital download or as a paperback from Amazon. Check her out on Instagram @yrnspinner or at joanneseiff.blogspot.com.