A round challah symbolizes a long life, or the unbroken circle of the full new year to come. (photo by Przemyslaw Wierzbowski)

On Rosh Hashanah, we are supposed to feast. Why? This is said to come from the passage in the book of Nehemiah (8:10): “Go your way, eat the fat and drink the sweet, and send portions unto him for whom nothing is prepared; for this day is holy unto our lord.”

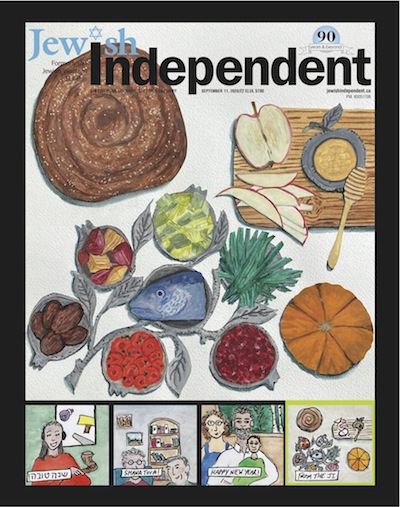

Round, sweet challah

The most common Rosh Hashanah custom for Ashkenazi Jews is the making of sweet challah, primarily round in shape, to symbolize a long life or the unbroken circle of the full new year to come. Some people place a ladder made of dough on top of the loaf, so our prayers may ascend to heaven, or because it is decided on Rosh Hashanah “who shall be exalted and who shall be brought low.” Some place a bird made of dough on top, derived from the phrase in Isaiah: “as birds hovering so will the Lord of Hosts protect Jerusalem.”

According to John Cooper, in Eat and Be Satisfied: A Social History of Jewish Food, the tradition in disparate Jewish communities of baking fresh loaves of bread on a Friday morning has its roots in the talmudic era. The custom was ignored by medieval rabbinic commentators, he writes, but was revived by the Leket Yosher, a report compiled by Joseph ben Moses in the 1400s on the teachings and practices of his teacher, Austrian Rabbi Israel Isserlin; and by Rabbi Moses Isserles, the 16th-century Polish scholar of halachah, at the end of the Middle Ages.

According to Jewish tradition, the three Sabbath meals (Friday night, Saturday lunch and Saturday late afternoon) and two holiday meals (one at night and lunch the following day) each begin with two complete loaves of bread. This “double loaf” (lechem mishneh) commemorates the manna that fell from the heavens when the Israelites wandered in the desert after the Exodus. The manna did not fall on Sabbath or holidays; instead, a double portion would fall the day before the holiday or Sabbath.

Pomegranate blessings

On the second evening of Rosh Hashanah, it is customary to eat a new fruit not yet eaten in the season and recite the Shehechiyanu, a prayer of thanksgiving for the first time something happens. It is said that, in Europe, this fruit was often grapes; in Israel today and around the diaspora, it is often the pomegranate.

The pomegranate is eaten to remind us that G-d should multiply our credit of good deeds, like the seeds of the fruit. For many Jews, pomegranates are traditional for Rosh Hashanah. Some believe the dull and leathery skinned crimson fruit may have really been the tapuach, apple, of the Garden of Eden. The word pomegranate means “grained apple.” In Hebrew, it is called rimon – also the word for a hand grenade!

Some say each pomegranate has 613 seeds for the 613 mitzvot, or good deeds, we should observe.

Symbolism of fish

The first course of the Rosh Hashanah holiday meal is often fish. Fish is symbolic of fruitfulness: “may we be fruitful and multiply like fish.” Fish is also a symbol of immortality, a good theme for the New Year, as are the ideas that we should aim to be a leader (the head) and that we hope for the best (to be at the top). Another reason for serving fish might be that the numerical value of the letters of the Hebrew word for fish, dag, is seven and Rosh Hashanah begins on the seventh month of the year.

Importance of tzimmes

Tzimmes is a stew made with or without meat and usually with prunes and carrots. It is common among Ashkenazi Jews, particularly those from Eastern Europe and Poland, and its origins date back to Medieval times. It became associated with Rosh Hashanah because the Yiddish word for carrot is mehren, which is similar to mehrn, which means to increase. The idea was to increase one’s merits at this time of year. Another explanation for eating tzimmes with carrots for Rosh Hashanah is that the German word for carrot was a pun on the Hebrew word, which meant to increase.

Tzimmes also has come into the vernacular as meaning to make a fuss or big deal. As in, they’re making such a tzimmes out of everything.

Lekach & other sweets

Among Ashkenazim, sweet desserts for Rosh Hashanah are customary, particularly lekach, or honey cake, and teiglach, the hard, doughy, honey and nut cookie. Some say the origin of the sweets comes from the passage in the book of Hosea (3:1): “love cakes of raisins.” There is also a passage in Samuel II (6:10) that talks about the multitudes of Israel, men and women, “to every one a cake of bread and a cake made in a pan and a sweet cake.”

Ezra was the fifth-century BCE religious leader who was commissioned by the Persian king to direct Jewish affairs in Judea and Nehemiah was a political leader and cup bearer of the king in the fifth century BCE. They are credited with telling the returned exiles to eat and drink sweet things.

According to Cooper’s Eat and Be Satisfied, references to honey cake were made in the 12th century by a French sage, Simcha of Vitry, author of the Machzor Vitry, and by the 12th-century German rabbi, Eleazar Judah ben Kalonymos. By the 16th century, lekach was known as a Rosh Hashanah sweet.

Among the Lubavitch Chassidim, it was customary for the rebbe to distribute lekach to his followers; others would request a piece of honey cake from one another on Erev Yom Kippur. This transaction symbolized a substitute for any charity the person might choose to receive, like the traditional kapparot ceremony, where, before Yom Kippur, one transfers their sins to a chicken.

Some Sephardi customs

Food customs differ among Jews whose ancestors came from Spain and Portugal, the Mediterranean area and primarily Muslim Arab countries. For example, whereas Ashkenazim dip apple in honey, some Sephardim traditionally serve mansanada, an apple compote, as an appetizer and dessert, according to Gil Marks (z”l) in The World of Jewish Desserts.

Just as gefilte fish became a classic dish for the Ashkenazi Jews, baked sheep’s head became a symbol – dating back to the Middle Ages – for many Sephardi Jews for Rosh Hashanah. Some groups merely serve sheep brains or tongue, or a whole fish (with head), probably for the same reason – fruitfulness and prosperity and new wishes for the New Year for knowledge or leadership.

The Talmud mentions the foods to be eaten on Rosh Hashanah as fenugreek, leeks, beets, dates and gourds, although Jewish communities interpret these differently. According to Rabbi Robert Sternberg in The Sephardic Kitchen, Sephardi Jews have a special ceremony around these and sometimes other foods, wherein each one is blessed with a prayer beginning “Yehi ratzon” (Hebrew for “May it be thy will”). The Yehi Ratzones custom involves preparing in advance and then blessing the Talmud-mentioned foods, or dishes made with the foods, as well as over the apples and honey, the fish or sheep head (some substitute a head of lettuce or of garlic) and pomegranate. In doing this, people recognize G-d’s sovereignty and hope He will hear their pleas for a good and prosperous year.

Sybil Kaplan is a Jerusalem-based journalist and author. She has edited/compiled nine kosher cookbooks and is a food writer for North American Jewish publications.