There are as many ways of celebrating Passover and the Pesach seder as there are Jews, and then some. Over the years, I have collected articles on different customs from around the world. Here are just some of the traditions surrounding food and the seder that I found unique.

Afghanistan

Haroset may contain walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, pomegranates, apples, sweet wine and black pepper. The seder meal begins with arak-like liqueur, hard-boiled eggs, fruit, cucumbers, fried fish, cold omelette, lettuce and potato pancakes. The main course is meat soup with vegetables then fruit and nuts. The seder in Afghanistan was conducted with people sitting on carpets.

Belgium

Sedarim were communal in small towns, conducted according to Orthodox customs. Chickens and meat were killed according to kashrut, and live carp swam in the bathtub until it was time to make the gefilte fish.

China

Passover candy called pasla was made of minced prunes, boiled in honey with nuts dropped in. When it began to harden, it was rolled up, so there would be nuts on the inside and outside, and sliced.

Cuba

The oldest member held the seder for the entire family, with all the food home-made except for the matzah, which was imported.

Egypt

Haroset is made with raisins and dates or figs mixed with wine and chopped walnuts. Raisins were also used to make wine. For the meal, there would be fish with lemon sauce, meat casserole and matzah, as well as meat-and-leek patties.

Jews of Egyptian-descent wrap the matzot in a sack-like package, which is passed to each member of the seder. While each member holds the sack in turn, the other attendees ask him in Arabic: “Where are you coming from?” to which he replies, “From Egypt.” “What are you carrying?” they ask. “Matzot.” “Where are you going?” “Jerusalem.”

Ethiopia

Everyone made their own matzah consisting of wheat or legume flour, water and salt, baked in very thin slices and eaten almost immediately to eliminate the possibility of leavening. They also interpreted the Hebrew word hametz, to rise or leaven, to mean kept or not fresh, so they would only eat fresh produce, fresh milk and freshly slaughtered meat.

Since the Ethiopian Jewish community – believed to be either descendants of the Israelite tribe of Dan or progeny of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba – practised a pre-talmudic form of Judaism, the Ethiopian seder was a less-structured affair with an informal, festival air, more like a springtime celebration. Events were focused on those in the Torah – the slaughtering of the paschal lamb, the Ten Plagues and Exodus itself. Since arriving in Israel, many families recount their own exodus from Ethiopia as part of the seder.

Germany

Men wore kittels for the seder. Sauerkraut was part of the meal along with kloesse, a dish made of soaked matzah, eggs and fried onions, made into a big ball and cooked in boiling water. This was eaten in place of potatoes, topped with brisket gravy.

Greece

Popular seder dishes include roast leg of lamb strongly flavoured with garlic; lamb pie with the animal’s heart, liver, lungs, kidney and intestines inside; and lamb stew with artichokes, served with an egg and lemon sauce.

India

The seder meal consisted of spinach baked with eggs, fried matzah with leeks and eggs, and a pudding made of matzah, meat and eggs. The seder plate was passed around the table, and each guest held it for a minute above their heads.

Iran

The youngest member of the family conducts the seder. When the plagues are mentioned, a pinch of salt is added to the wine. During the song “Dayenu,” long-stemmed onions are put together in a bunch and one person “whips” the person next to them and then passes on the bunch of onions, to be similarly used by all the guests, until the onions make their way around the table. Often family members act out the Exodus, sometimes in costumes.

Italy

Squares of matzah, soaked in capon broth, browned in goose fat and baked in alternating layers with cooked greens or poultry giblets was a seder favourite. Other unusual Italian dishes are rib chops from lambs, ground chicken or ground beef meatballs.

In Venice, the squares were cooked in a pan with legumes such as peas, fava beans or lentils. Venice was famous for unleavened cakes in the shape of snakes, unleavened cakes stuffed with marzipan and doughnuts rolled in sugar and cinnamon.

Passover pasta in broth, boiled meat with goose salami, salad and a marzipan or matzah meal dessert and quince preserves were part of the Urbino seder.

Boiled chestnuts were used in haroset in northern Italy. Tuscan Jews made matzah and egg cakes. Ferrara Jews made matzah fritters with egg, honey, cinnamon, candied citron, pine nuts and raisins. Jews in Rome made lemon sorbet, almond cookies and wet matzah, squeezed dry and fried in olive oil then served with pine nuts, raisins and heated honey.

The table is adorned with long-stemmed green onions. During the chorus of “Dayenu,” everyone picks up their onion and “whips” the wrist of someone adjacent to them. This is meant to represent the sounds of whips of the slave masters in Egypt.

Mexico

No dairy products are used during Passover, tea is drunk instead of coffee and the seder meal is hot and spicy.

Morocco

Matzah is handmade, placed in ovens and allowed to cook for only five minutes. Tagine with lamb and almonds, prunes, saffron, cinnamon, ginger and honey is a Passover mainstay, as are truffles.

The seder plate was held over each person’s head while the others at the table recited in Arabic, “Just as G-d took us out of Egypt and split the sea for us, so may he save us today.”

Based in kabbalah, Jewish mysticism, they divided the soft doughy matzah they eat into the shapes of the Hebrew letters daled and vav; daled stands for doorposts of Israel that G-d watched over and vav is a symbol for G-d’s name.

Netherlands

Prior to a seder meal, a dish of sauerkraut or chard mashed with potatoes and accompanied by cold corned beef was served. For the seder, matzah balls in soup and roast meat or chicken was served. Haroset was nuts, raisins, apples, sweet wine, cinnamon and sugar. A second seder meal was dairy with matzah, butter, cheese, sometimes fish cakes, coffee and cake of ground nuts or mashed potatoes. Matzah pancakes with apple sauce or pareve lemon cream was also served. Tongue with meatballs was part of some people’s Passover meals.

Rhodes

Romaine lettuce was used instead of horseradish. Fish with a Greek-style lemon sauce or cooked with tomato sauce, or with rhubarb and tomatoes, is served at the seder meal.

Syria

Seder foods include lamb shanks and rice; haroset made from dried fruits, sweet wine, cinnamon and crushed walnuts; spinach-mint soup; and flourless pistachio cookies.

Tunisia

Lamb stew with leeks, spinach, peas, fennel, carrots, artichokes, turnips, cabbage, celery, potatoes and zucchini are flavoured with cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, salt, pepper, cilantro, dill and mint for Passover.

Yemen

The entire table is made into one big seder plate, with a border of parsley leaves all along the edges. The matzah resembles pita because they believe that, as long as the dough is continuously kneaded, it will not turn into hametz.

Sybil Kaplan is a Jerusalem-based journalist and author. She has edited/compiled nine kosher cookbooks and is a food writer for North American Jewish publications. She leads walks of the Jewish food market, Machaneh Yehudah, in English.

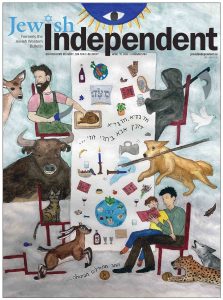

There are numerous interpretations of Chad Gadya (One Little Goat), which ends the Passover seder. A cumulative song, like “There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly,” it starts with Father buying a goat, which is then eaten by a cat. Because it’s easier to summarize from the end, the last verse is, depending on your translation: then came the Holy One, Blessed be He, and slew the angel of death, who killed the butcher, who slaughtered the ox, that drank the water, that quenched the fire, that burnt the stick, that beat the dog, that bit the cat, that ate the goat. The Hebrew on the table in the cover image is the beginning of the song: Chad gadya, chad gadya, d’zabin Aba bitrei zuzei (that Father bought for two zuzim).

There are numerous interpretations of Chad Gadya (One Little Goat), which ends the Passover seder. A cumulative song, like “There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly,” it starts with Father buying a goat, which is then eaten by a cat. Because it’s easier to summarize from the end, the last verse is, depending on your translation: then came the Holy One, Blessed be He, and slew the angel of death, who killed the butcher, who slaughtered the ox, that drank the water, that quenched the fire, that burnt the stick, that beat the dog, that bit the cat, that ate the goat. The Hebrew on the table in the cover image is the beginning of the song: Chad gadya, chad gadya, d’zabin Aba bitrei zuzei (that Father bought for two zuzim).