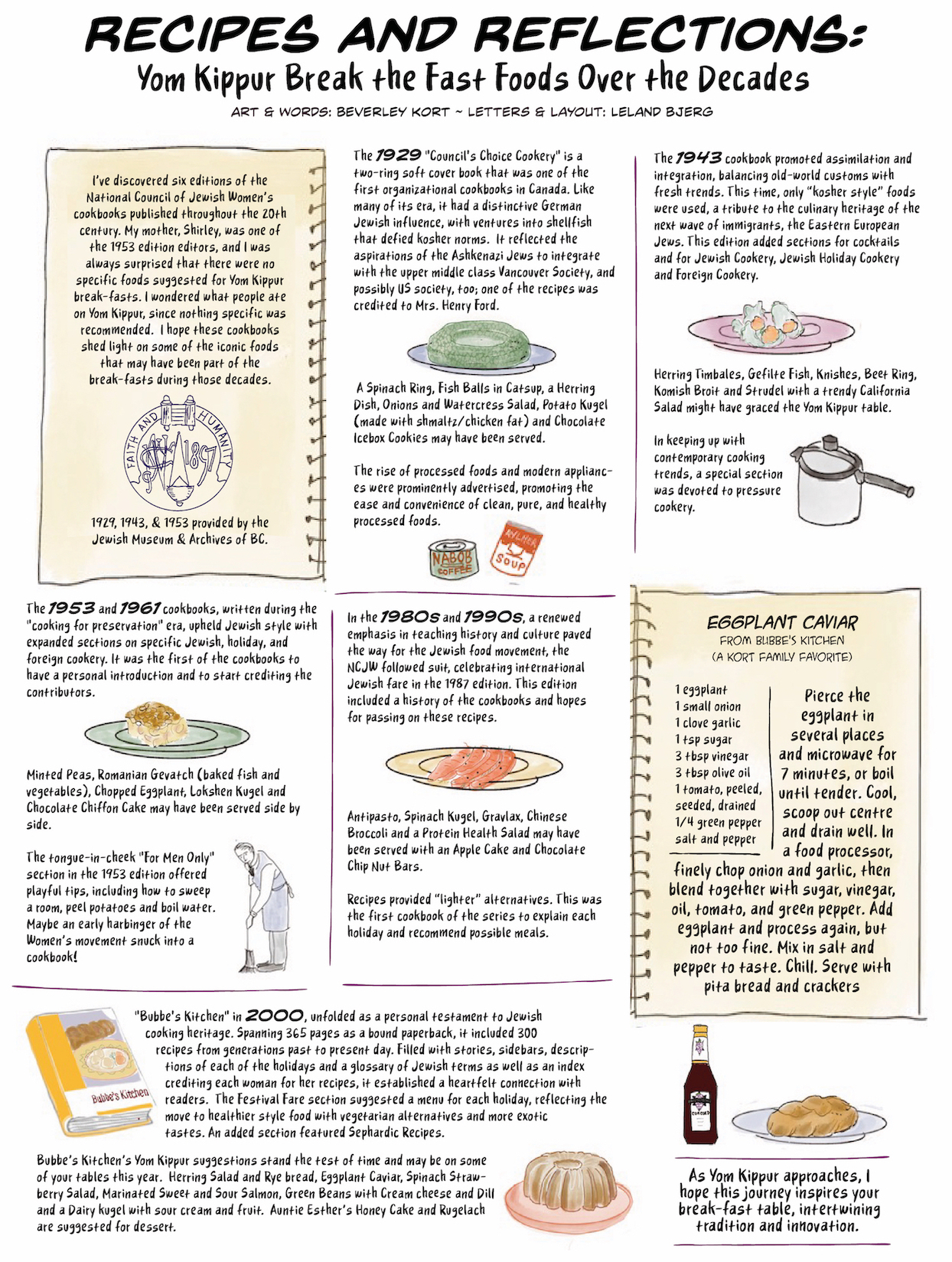

A family performs the kapparot ritual with two hens and a rooster, circa 1901. (photo from Library of Congress via brandeis.edu)

Whether or not the custom of eating chicken for a High Holiday meal arose from a desire to replace the ritual of kapparot, roast chicken is often served at the holiday table. Here are a few chicken recipes you might like to try this new year, as well as sweet potato sides and desserts made with pomegranates – another food with holiday symbolism. A coffee cake is always good to have on hand for visitors, or to help break the Yom Kippur fast.

ROAST HERBED CHICKEN

1 3-pound chicken

4 garlic cloves

2 bay leaves

3 tbsp melted unsalted pareve margarine

salt and pepper to taste

1/4 tsp thyme

1/4 tsp sage

1/4 tsp oregano

1/4 tsp marjoram

1/4 tsp basil

- Preheat oven to 425ºF. Grease a baking pan.

- Rinse and dry chicken. Rub skin with 1 cut garlic clove, then place it inside chicken with other cloves and bay leaves.

- In a bowl, mix margarine with salt, pepper, thyme, sage, oregano, marjoram and basil. Place 1 tablespoon inside chicken, tie legs together and place, breast side down, in baking pan. Brush the rest of the spiced mixture over the outside of the chicken. Bake 45 minutes. Turn it over and bake 40-45 minutes longer.

SIMPLEST ROAST CHICKEN

1 5-pound chicken

1 lemon cut in half

4 garlic cloves

4 tbsp unsalted pareve margarine

salt and pepper to taste

1 cup chicken soup, water or wine

- Preheat oven to 500ºF. Grease a roasting pan.

- Remove excess fat, neck, gizzards and liver. Combine lemon, garlic, margarine, salt and pepper in a bowl and stuff inside chicken.

- Place chicken breast side up in a baking pan with legs facing the back of the oven. Roast 10 minutes then move with a wooden spoon to keep it from sticking. Continue roasting 40-50 minutes.

- Tilt chicken to get juices into roasting pan. Remove chicken. Put juices in a pan, add soup, water or wine and bring to a boil. Reduce liquid by half. Serve sauce in a bowl or pour over chicken.

CHICKEN WITH DRESSING

(this was a favourite of my mother, z”l)

1 5-pound chicken

salt to taste

3/4 tsp ginger

1 sliced onion

1/2 cup celery

your favourite stuffing

3/4 cup boiling water

4-6 sliced potatoes

- Preheat oven to 400ºF. Grease a roasting pan.

- Sprinkle chicken cavity with salt and ginger. Place in roasting pan. Stuff with your favourite stuffing. Add onion and celery. Roast 20 minutes.

- Reduce temperature to 350ºF and bake 20 minutes more. Add boiling water and potatoes and continue baking 1 1/2 hours more.

MY MOM’S (Z”L) CANDIED SWEET POTATOES

8 sweet potatoes

1/4 cup brown sugar

1 tsp cinnamon

1/2 cup crushed nuts (optional)

2 tbsp margarine

2 tbsp non-dairy creamer

2 tbsp orange juice

- Preheat oven to 350ºF. Grease a casserole dish.

- Boil sweet potatoes in water until soft. Remove, cool and peel. Place in a bowl and mash.

- Add brown sugar, cinnamon, nuts, margarine, non-dairy creamer and orange juice. Spoon into greased casserole and bake 30-45 minutes.

MY SABRA SWEET POTATOES

6 oranges

1/4 cup Sabra liqueur

6 tbsp margarine

2 tbsp brown sugar

1/4 tsp nutmeg

4 cooked, peeled, smashed sweet potatoes

- Preheat oven to 350ºF. Grease a casserole dish.

- Cut oranges in half and scoop out pulp.

- Place mashed sweet potatoes in a mixing bowl.

- In a saucepan, combine Sabra, margarine, brown sugar and nutmeg. Simmer for three minutes. Pour over sweet potatoes.

- Spoon potatoes and sauce into orange halves. Bake 30 minutes.

APPLE-POMEGRANATE COBBLER

(This recipe is adapted from a Food & Wine recipe)

2 cups pomegranate juice

6 peeled, halved, cored, sliced 1/2-inch thick apples

1 cup sugar

2 1/4 cups flour

kosher salt

2 tsp baking powder

1 stick cold unsalted butter, cut into small pieces, or 1/2 cup unsalted pareve margarine

1 cup cold heavy cream or pareve cream

pomegranate seeds

pareve vanilla ice cream

- Preheat oven to 375ºF. Place an eight-by-eight glass baking dish on a foil-lined rimmed baking sheet.

- In a small saucepan, bring pomegranate juice to a boil over high heat, reduce to 1/3 cup (approximately 15 minutes). Pour into a bowl. Fold in apple slices, 3/4 cup sugar, 1/4 cup flour and 1/2 tsp salt. Put into baking dish.

- In a bowl, whisk 2 cups flour, 1/4 cup sugar, baking powder and 1/2 tsp salt. Add butter or margarine and cut until mixture resembles coarse crumbs. Stir in 1 cup cream.

- Gather topping and scatter over apple filling. Brush top with cream, sprinkle with sugar. Bake 60-70 minutes or until filling is bubbling and topping is golden. If crust is browning, tent with foil.

- Let cool for 20 minutes. Sprinkle with pomegranate seeds. Top with vanilla ice cream.

POMEGRANATE ICE

(makes 5 cups)

8-10 seeded pomegranates

3-4 tbsp lemon juice

1 1/2 tsp grated lemon peel

3/4 cup sugar

- Whirl pomegranate seeds in blender. Strain and save liquid for 4 cups.

- Add lemon juice, lemon peel and sugar. Pour into a metal pan and cover with foil. Freeze 8 hours. Remove and break into chunks. Blend into slush. Refreeze until firm.

SOUR CREAM COFFEE CAKE

3 cups flour

1 1/2 cups sugar

1 1/2 tsp baking soda

1 1/2 tsp baking powder

salt to taste

3/4 cup butter or margarine, melted

1 1/2 cups sour cream

3 eggs

1 1/2 tsp vanilla

1/2 cup chopped nuts

2 tbsp sugar

1 tbsp cinnamon

1/4 cup chopped nuts

- Preheat over to 350ºF. Grease a baking pan.

- In a mixing bowl, mix flour, sugar, baking soda, baking powder and salt.

- Add butter or margarine, sour cream, eggs and vanilla and mix.

- Add nuts and blend well. Pour half into baking pan.

- In a bowl, mix sugar, cinnamon and nuts. Pour over batter. Add rest of batter. Bake 1 hour.

QUICK CRUMB COFFEE CAKE

2 1/4 cups flour

3 tsp baking powder

salt to taste

1 cup sugar

6 tbsp unsalted margarine, melted

1 egg

3/4 cup milk

1 1/2 tsp vanilla

1/2 cup brown sugar

2 tbsp flour

2 tsp cinnamon

2 tbsp crumbled margarine

1/2 cup chopped nuts

- Preheat oven to 350ºF. Grease a baking pan.

- In a mixing bowl, blend flour, baking powder and salt. Add sugar, margarine, egg, milk and vanilla and blend well.

- Spread batter on bottom of greased baking pan.

- In a small bowl, combine brown sugar, flour, cinnamon, margarine and chopped nuts. Sprinkle on top of batter. Bake 30 minutes or until a toothpick inserted in the centre comes out clean.

Sybil Kaplan is a Jerusalem-based journalist and author. She has edited/compiled nine kosher cookbooks and is a food writer for North American Jewish publications. She leads walks of the Jewish food market, Machaneh Yehudah, in English.