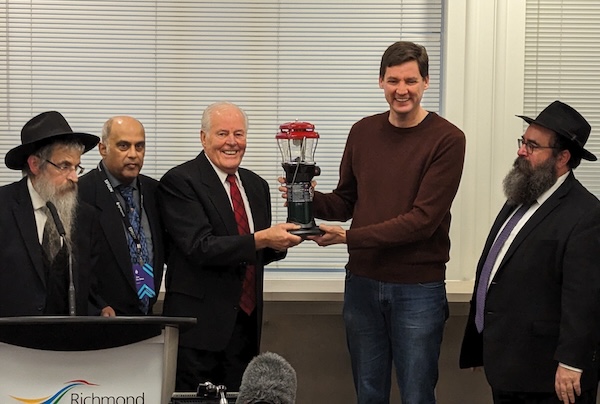

Hundreds attended the lighting of the Silber Family Agam Menorah on the first night of Hanukkah Dec. 7, where politicians from all levels of government offered holiday greetings and support. (photo by Pat Johnson)

Hundreds gathered outside the Vancouver Art Gallery on the first night of Hanukkah, Dec. 7, to kindle light in the darkness. The decades-old annual event led by Chabad Lubavitch BC had even more than the usual sense of familiarity, as the Jewish community has been gathering weekly on the same site since the Oct. 7 pogrom, and Hanukkah’s messages of hope amid tragedy reinforced the words that have been shared from the podium over recent weeks.

The art gallery event, as well as a community menorah lighting Sunday in Richmond, was attended by many elected officials – including the premier of British Columbia and the provincial opposition leader at both ceremonies. Ezra Shanken, chief executive officer of the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver, reiterated his gratitude for the support shown to the community in times of trouble.

The first night event was co-hosted by Karen James and Howard Blank and was produced by Richard Lowy, who sang and played guitar. Children from Jewish schools and public schools sang Hanukkah songs. Spoken word artist Vanessa Hadari performed.

The first candle on the Silber Family Agam Menorah was lit by Etsik Mizrachi and Dan Mizrachi, father and brother, respectively, of Ben Mizrachi, the Vancouver man who was killed Oct. 7 while attempting to save others under attack at the music festival in Israel, where more than 360 people were murdered by Hamas terrorists.

“This is a time of darkness in the world,” said B.C. Premier David Eby. “British Columbia is a place of tolerance and we need to be like the light on the menorah – we need to be a light against hatred.”

Speaking on behalf of the provincial government, Eby promised to do “all we can to push back against the tide of rising hate around the world.”

He spoke of meeting Dikla Mizrachi, mother of Ben, before addressing the assembly.

“It’s moving to meet the mother of a hero, a man from Vancouver who didn’t run away from danger. He ran back to help a friend,” said the premier, “and it cost him his life.”

In a message he repeated in Richmond a few days later, Eby said he prays for the release of the hostages and for peace.

Kevin Falcon, British Columbia’s leader of the opposition, also spoke both in Vancouver and in Richmond.

“I cannot think of a time in my lifetime that the message of Hanukkah, the triumph of good over evil, light over darkness, has resonated and been so meaningful to all of us,” he said on the first night of Hanukkah. “In the wake of that horrific tragedy, we’ve seen unfortunately some really vile antisemitism in the weeks that followed. Sadly, we’ve seen some of that even here in British Columbia and in Canada.”

Falcon received a resounding ovation on both occasions when he acknowledged Israel’s right to defend itself.

“Something must be made really crystal clear, and that is that Israel has a right to exist, Israel has a right to defend itself and the Jewish community here in British Columbia has the right to feel safe and secure,” said Falcon.

Vancouver Mayor Ken Sim, flanked by many Vancouver city councilors, said, “It’s a really tough time.”

“While we can’t unwind what’s going on, I can tell you that … we love you and we will always be here for you,” said the mayor. “You are our family, you are our friends, you are our neighbours. We have your back. We are not going to stand for any acts of hatred.”

Messages of support from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and federal opposition leader Pierre Poilievre were read aloud.

“In a country built by immigrants, the contribution that Jewish Canadians have made and continue to make every day to our shared nation are indeed invaluable,” Trudeau wrote.

“For generations,” Poilievre wrote, “the menorah has been a symbol of strength and comfort to the Jewish people. In times of darkness, it has carried a message of hope. In times of oppression, it has been an emblem of freedom. Today, it continues to bring encouragement to Jewish people in Israel, here in Canada and around the globe. Unfortunately, this message of hope is needed now more than ever.”

Jim DeHart, consul general of the United States to British Columbia and Yukon, also spoke, promising that the United States will not stand by in the aftermath of such attacks.

“We won’t be silent in the face of antisemitism and we will continue to work to defeat hate and prejudice in all of its forms,” he said.

Rabbi Dovid Rosenfeld compared current events with the Hanukkah story.

“In the glow of these menorah lights, we find inspiration and the triumph of light over darkness, hope over despair and freedom over oppression,” he said. “Even in the face of challenges that may seem insurmountable, the human spirit can prevail and miracles can unfold.… In the face of darkness, we choose to be the light.”

Herb Silber, son of the late Fred Silber, who donated the menorah that is lit annually at the Vancouver Art Gallery, spoke of the vision of his father and his father’s contemporaries, who built British Columbia’s Jewish community.

“It would be with a heavy heart if those pioneers like my father were here today to witness a rise in antisemitism that, while bubbling on the surface these last few years, has now burst into the open and become mainstream,” he said. “So, I come back to the holiday of Hanukkah because it reminds us that the story of antisemitism is not a new phenomenon. It is 3,500 years old, and the attempt to separate the Jewish people from their indigenous land of Israel is also not a new phenomenon. But what history has shown us is that Jews like my father and his contemporaries and those that came before him, and indeed the story of the Jewish people, is that we are a resilient people.

“One disappointment that marks these historic outbreaks of antisemitism,” he continued, “has been the silence of the non-Jewish community and, regrettably, we have seen evidence of that in events of the past two months. But, gathering here tonight reminds us that we have friends on the stage and elsewhere. And we know that the silent majority of our Canadian neighbours and our friends cherishes each one of us as Canadians, as we do them.”

Lana Marks Pulver, chair of the board of the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver, thanked the Vancouver police for ensuring the safety of the community, and noted that antisemitic hate incidents reported in October were up 350% over the same month a year earlier.

Members of the Rabbinical Association of Vancouver stood on stage, days before most of them left Sunday for a three-day mission to Israel.

Rabbi Dan Moskovitz, flanked by seven other rabbis who are on the mission, said he will carry the light of the Vancouver community to the people of Israel.

“We are going because of your light, which shines so brightly in this dark time,” said Moskovitz, senior rabbi at Temple Sholom. “We are going to bring that light, the message of Hanukkah, of resilience, of dedication, of rededication, of religious freedom, of the few fighting to preserve freedom against the many who seek to destroy it, and us in its process. We are going to assure Israelis that they are not alone, that the people of Vancouver stand with them.”

The rabbis, according to Moskovitz, will meet with Israeli thought leaders, Oct. 7 survivors, the wounded, Jewish and Arab Israelis, and others, “to hear with our own ears what people experienced on Oct. 7 and what it has been like in the months since.”

They will also bring cold weather gear to soldiers, especially in the north, who have not been able to leave their posts to replenish supplies.

On Sunday, Dec. 10, almost every one of Richmond’s elected officials at the federal, provincial and municipal level was present to hear rabbis speak and to see the premier and Richmond Mayor Malcolm Brodie light the shamash and the first candle. Community leaders Jody and Harvey Dales lit the successive candles.

The Richmond event began 35 years ago and joining Eby on Sunday was Bill Vander Zalm, who was premier at the time and lit the menorah on the first year a public lighting was held.

Rabbi Levi Varnai of the Bayit emceed the Richmond event and said it was the Lubavitcher Rebbe who revived the ancient tradition of public menorah lightings, which, over the centuries, had fallen out of favour for fear of persecution. Richmond was among the first communities to institute the celebration, he said, thanks to Rabbi Avraham Feigelstock, who also spoke Sunday.

In addition to the rabbi and the former premier, numerous people who were at the first menorah lighting 35 years ago were also in attendance Dec. 10, including Joe Dasilva, who has organized every annual menorah lighting. He retired from the Ebco Group of Companies, whose founders, Helmut and Hugo Eppich, donated the Arthur Erickson-designed menorah. Richard Eppich, now president of the family business, attended Sunday.