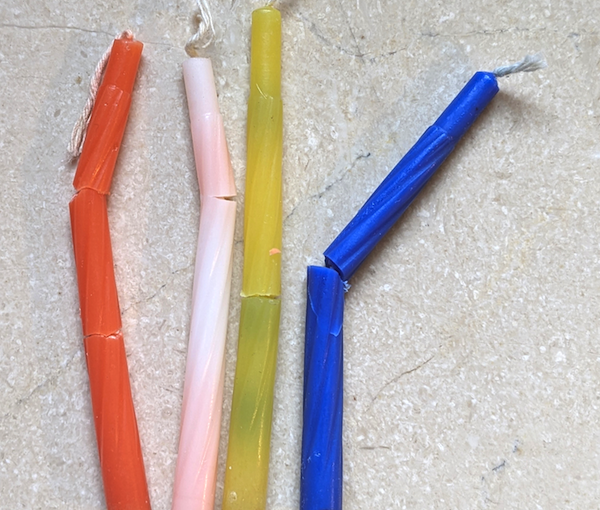

(photo by Jon Sullivan)

In the village of Chelm, just before every Chanukah, the ancient debate begun by the two great rabbis Hillel and Shammai resumed. Do you start the festival by lighting one candle and counting up, or with eight and counting down?

Every year, Rabbi Kibbitz issued the same ruling – do whatever makes you happy.

This year, although the argument was heated, rumour was that Rabbi Kibbitz was bedridden. He was old. Was he sick? He was tired.

It was worrisome that his wife, Mrs. Chaipul (she kept her name, which is another story), who owned the only kosher restaurant in Chelm, hadn’t been to work in three days.

Filling in behind the restaurant’s counter, Rabbi Yohon Abrahms, the schoolteacher and mashgiach, was cooking, cleaning and taking orders.

“So, about the Chanukah candles,” Reb Cantor the merchant asked the young rabbi, who was busy refilling cups of tea, “how many on the first night and how many on the last?”

Rabbi Abrahms answered with a shrug. “Rabbi Kibbitz always says, do whatever makes you happy.”

“But you’re a rabbi, too,” Reb Cantor said. “What do you think?”

“Do you want food or a theological dissertation?” Rabbi Abrahms shot back. “Because I can’t do both at the same time!”

The room fell quiet.

“Food, of course!”

In Chelm, food was always more important than discussion – until it was gone, then discussion.

* * *

“Channah, you should go to your restaurant,” Rabbi Kibbitz said. His voice was soft.

“No, my love,” Mrs. Chaipul said. “I’ve left it in good hands. I will stay here with you.”

“It’s OK,” he said. “I’m not going to die until after Chanukah.”

“Don’t say such things.” She made the sign against the evil eye.

“Will you cry when I go?”

“For you? Probably.” She was barely holding back the tears. “But enough. We have years ahead.”

“No.” He sighed. “We’ve had years. Good years. Many, but not enough. Never enough. Now we have only days.”

He began coughing, and she fed him spoonfuls of warm chicken soup.

“Channah?”

“I’m here.”

Do you know what the problem with sitting shivah is?”

“Too much noodle pudding?”

“True.” The rabbi laughed, then he coughed. “Shivah is meant to comfort the living, but I’ve noticed that most bereaved are very uncomfortable. Mourning is overrated. For a week, everyone visits and talks about the recently deceased. And the family has to sit and listen, no matter how tired or sad…. All they really want is their loved one back.”

“Shaa, shaa,” his wife said. “Your shivah is a long way off.”

“No. But I have a request.”

“What is it?”

“During Chanukah,” the old rabbi said, “let me sit shivah with you, before I’m dead. Then you won’t be so alone.”

She covered her mouth to stifle a sob. What a foolish request!

Then she nodded. “Yes. Yes. Of course.”

* * *

It caused quite a stir in the village.

“If he’s not dead, how is it shivah?”

“We’re going to talk about him while he’s lying there in the house?”

“After he dies for real, are we going to have to do another shivah?”

“And what if he doesn’t die?”

This last question was interesting, because no one really believed that Rabbi Kibbitz would ever die. He was a bear of a man, who had been old forever. How could one such as that pass on?

Still, Chelm was a village that embraced the unconventional.

A schedule was made and, on each night of Chanukah, a different group trudged through the snow to light the candles and sit shivah.

The two-room house was small. The table was moved to the side of the kitchen, and extra chairs brought in for visitors. The rabbi’s bed was set in the doorway of the bedroom, so he could sit up or lie down as needed. Mrs. Chaipul’s sewing chair was next to the doorway, so she could sit beside him.

This living shivah turned out to be quite a success, mostly because the rabbi kept his mouth shut and said nothing. Everyone forgot that he was there.

Each night, blessings were sung and candles were lit. Most of the villagers were counting up with Hillel, but some were counting down with Shammai. No matter how many or how few, the light was warm and bright.

Yes, there was noodle kugel, but there were also latkes, so many different kinds, including potato, sweet potato and even zucchini.

Every villager stopped by and shared stories of how Rabbi Kibbitz had listen, talked, helped, advised or officiated. There had been weddings and brises, funerals and so many sermons.

Mrs. Chaipul listened to all the praise, and the occasional complaint. She accepted comfort and hugs, and wondered at the frequent comment, “What will we do now that he is gone?”

Strangely, hearing these words while her husband was still breathing didn’t leave her as sad as she’d expected. She found herself reliving their life together.

“He never had children with his first wife,” she told everyone. “And we, of course, were too old. But he always told me that he didn’t need any kinder because the whole village was his family.”

At last, on the eighth night of Chanukah, by some silent agreement, only the younger villagers came to visit. They all had chosen, with Shammai, to light just one candle.

There was wine and laughter and spirited discussion about the many texts that they had read with the rabbi.

Rachel Cohen said that she was proud to have been the rabbi’s first female student.

Her husband, Doodle, agreed that, without Rabbi Kibbitz, none of his many questions about life and death would have been answered so well.

A hush fell over the room as Doodle mentioned death.

The last few Chanukah candles sputtered and one by one extinguished.

All eyes turned to Mrs. Chaipul, who began to cry softly.

Except for the coals from the stove, the room was black.

“Is he?” someone whispered.

“We should go,” whispered another.

“Why is it so dark and quiet?” came a booming voice. “Am I dead?”

“He’s very noisy if he is dead,” said Doodle.

Rachel Cohen quickly snatched up a spare candle and lit it from the stove.

In the dim light, everyone looked and saw Rabbi Kibbitz was sitting up in his bed.

“Hello,” he said. His eyes glinted brightly. “I’m sorry to interrupt. You all said such nice things about me. Thank you. But I don’t think I’m done yet. I’m feeling much better. Channah, maybe you and I could leave Chelm together and do some traveling?”

“You old fool!” His wife threw her arms around his neck.

Rabbi Kibbitz hugged her close, and thought about the days to come; each of them an adventure to be shared.

One by one, but all at once, the students sneaked out of the house to spread word of the miraculous recovery.

The next morning, when a delegation of elders went to the rabbi’s house, they found it empty.

A note on the kitchen table read, “No, we’re not dead. Yes, we’ve gone. Shalom.”

Mark Binder is an author and storyteller. The former editor of the Rhode Island Jewish Herald – back when there was such a thing as a for-profit Jewish newspaper – writes the “Life in Chelm” series of books and stories. The first volume, A Hanukkah Present, was the runner-up for the National Jewish Book Award for family literature. The Brothers Schlemiel was serialized for two years in the Houston Jewish Voice. Binder’s a graduate of the Trinity Rep Theatre Conservatory, studied storytelling with Spalding Gray, and has taught the course Telling Lies: How To at the Rhode Island School of Design. He’s toured the world telling stories to listeners of all ages and backgrounds with the secret mission of transmitting joy with story. Readers can listen to the audio version of “The last candle” story at transmitjoy.com/spotify.

As Abrahmson explains in The Village Twins, Chelm is “a tiny settlement of Jews known far and wide as the most concentrated collection of fools in the world.” According to The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, the “first publication of Chelm-like stories appeared in Yiddish in 1597, and were tales of the town of Schildburg, translated from a German edition. Hence, these stories first entered Jewish culture as Schildburger stories, and it is unclear when they became connected to the town of Chelm. During the 19th century, a number of other Jewish towns figured as fools’ towns, including Poyzn. Over time, however, Chelm became the central hub of such stories, the first specific publication of which occurred in an 1867 book of humorous anecdotes, allegedly written by Ayzik Meyer Dik. Later, particularly in the early 20th century, dozens of collections of Khelemer mayses (Chelm stories) were published in Yiddish, as well as in English and Hebrew translations.”

As Abrahmson explains in The Village Twins, Chelm is “a tiny settlement of Jews known far and wide as the most concentrated collection of fools in the world.” According to The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, the “first publication of Chelm-like stories appeared in Yiddish in 1597, and were tales of the town of Schildburg, translated from a German edition. Hence, these stories first entered Jewish culture as Schildburger stories, and it is unclear when they became connected to the town of Chelm. During the 19th century, a number of other Jewish towns figured as fools’ towns, including Poyzn. Over time, however, Chelm became the central hub of such stories, the first specific publication of which occurred in an 1867 book of humorous anecdotes, allegedly written by Ayzik Meyer Dik. Later, particularly in the early 20th century, dozens of collections of Khelemer mayses (Chelm stories) were published in Yiddish, as well as in English and Hebrew translations.”