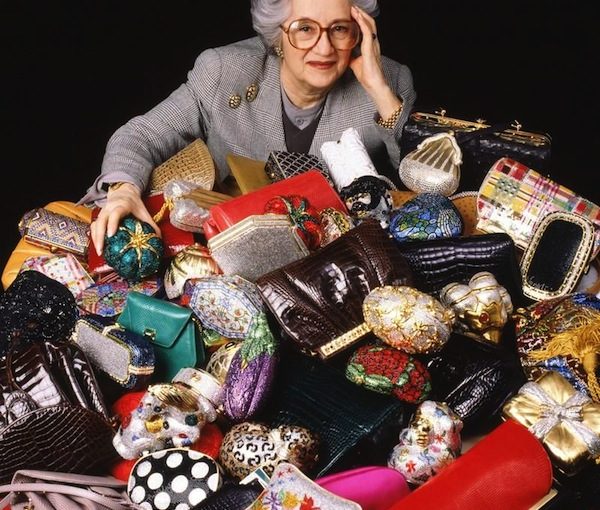

The Museum of Jewish History in Sosua is located right next to the city’s synagogue. (photo by Dave Gordon)

Famous for its rum, cigars, resorts, beaches and rich history, the all-season holiday destination of the Dominican Republic attracts 800,000 Canadians each year. Moreover, the country has a relatively unknown past – few people realize, or know, that the country opened its doors wide to Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution.

This era is chronicled at the Museum of Jewish History, in Sosua, which is in the northern section of the country. Located right next to the city’s synagogue, the museum preserves the memory of those Jewish refugees who sought a safe haven on Dominican soil, and left their mark on the region. It houses photographs of early-to-mid-20th-century Jewish immigrants, along with diary entries, ritual items and copies of letters from Jewish agencies during the war.

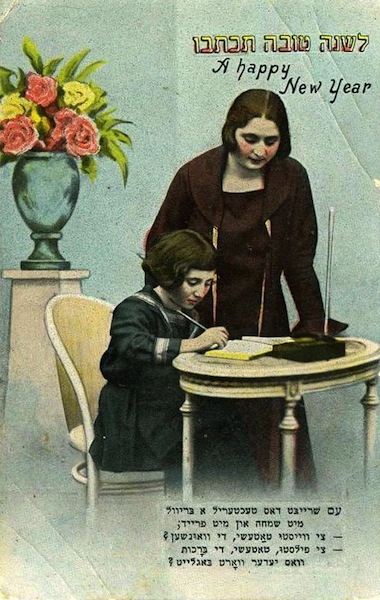

Before the Second World War, in 1938, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt summoned the Allies to Evian, France, for a conference about how to handle the massive exodus of Jews who desperately sought to flee Nazi persecution. Though most of the participants at the conference expressed their sympathy, no resolution was formulated. Paraphrasing Chaim Weizmann (who would later become the first president of Israel), Central and Eastern European Jews perceived the world as consisting of just two camps: one that hounded and hunted them, and another that closed its gates.

There was, however, one notable exception.

Of the 32 countries that sent delegations to the conference, only the Dominican Republic, led by President Rafael Trujillo, agreed to receive 100,000 refugees, offering land resettlement under generous conditions. A group of experts on refugee affairs, under the leadership of James Rosenberg, was mobilized by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee to capitalize on the offer. This was the birth of the Dominican Republican Settlement Association (DORSA).

Between 1940 and 1945, the Dominican Republic government issued 5,000 visas for displaced Jewish refugees. Tragically, however, the actual number of immigrant arrivals never reached anywhere near this figure, due to the escalation of the war, and also to what some believe to be mishandling by the Jewish Agency, which resulted in delays. Of the nearly 1,000 Jews who settled in the Dominican Republic, most were from Austria and Germany, although some came from as far away as China, and some from as close as the Caribbean islands.

Little by little, the jungle-like territory was divided into residential lots and communal barracks for arriving refugees. Each refugee was furnished with, as a repayable loan, 80 acres of land, 10 cows, one mule, one horse, and a living wage for a month. They were assisted with training in agriculture and farming techniques, of which most had little previous knowledge.

Jews took to food manufacturing, becoming successful in the production and sale of sausage, milk, cheese, tomato sauce, mashed carrots, stuffed peppers and mashed spinach. Many of these industries continue to this day. The refugees’ earnings enabled them to pay their debts and establish other small industries.

By the 1990s, however, just 36 Jewish families remained in Sosua, as most of the population either died, intermarried or moved to larger Jewish communities.

Interestingly enough, well before the arrival of these refugees, in 1916, the Dominican Republic briefly had a Jewish head of state, President Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal.

Visiting the country

Virtually every major supermarket has plenty of items with kosher certification, including imported canned goods, breads, fish and spreads. A Puerto Plata resort named Lifestyle has an on-site kosher restaurant, though only for guests staying there. Alternately, in Punta Cana, the local Chabad offers à la carte food orders upon request.

If this trip is a do-it-yourself getaway, as opposed to an all-inclusive, here are two suggestions for luxury stays that will offer the feel of home:

Villas Agua Dulce is a jaw-droppingly elegant and spacious facility. Each villa has a fully furnished living room, dining room and a washer/dryer. Three-bedroom villas are available to accommodate a family of seven. Toss in for good measure an outdoor patio, outdoor private pool, a spa centre, tennis and basketball courts, and Bauhaus interior design.

With the beach just a few hundred feet away, Cabarete Palm Beach Condos is centrally located in the Cabarete area. Each condo has a fully equipped kitchen, living room (with big TV), dining area and outdoor patio.

As for suggested adventures in the Puerto Plata area, I have several.

Monkey Jungle: After enjoying the 4,500-foot, seven-station zip lines overlooking the trees, visit the adjacent capuchin monkey reserve. Scores of these adorable creatures bounce around from tree to tree, hopping on your shoulders and nibbling straight from the fruit plate in your hand.

Ocean World: This is where you can swim with sharks and dolphins and kiss the sea lions.

Tip Top Catamaran: Take a ride on the 75-feet-long and 33-feet-wide catamaran. Tourists are offered the chance to experience the vibrant underwater world through snorkeling Sosua Bay (equipment is provided). Immerse yourself in schools of fish, peer at the coral, get face-time with a puffer fish and play with the sea urchins.

Twenty-seven waterfalls of Rio Damajagua are tucked away in the hills of the Northern Corridor mountain range, behind tall stalks of sugar cane. In addition to the mélange of outdoor activities – such as cliff jumping into natural waters and climbing through caves – you are surrounded by forest. And, depending on the season, fruit will be growing from coconut, avocado, coffee bean and mango trees.

Kiteboarding: Think of yourself hovering over the ocean on a surfboard, propelled by a giant inflatable kite, and you have kiteboarding. Dare2Fly provides kiteboarding packages, lessons and rentals.

Rancho Luisa y Tommy: Try a morning horseback ride. Run by 30-year-old Tommy Bernard, a Quebec expat, he’s an affable fellow who’ll treat you to engaging conversation on topics including animals, his adopted country, and most anything in life.

Dave Gordon is a Toronto-based freelance writer whose work has appeared in more than 100 publications around the world.