Tag: therapy

Special visitors at Louis Brier

Loni the Percheron Horse comes in the entrance of the Louis Brier Home and Hospital. (photo from Louis Brier)

Loni the Percheron Horse and his side kick Beau the Shitzu visited the Louis Brier Home and Hospital the afternoon of Sept. 7. This was the third (and last) time this year that the pair visited the home.

The program is designed to give residents the opportunity to have a personal experience with one of these beautiful, gentle giants – and not-so-giants – in the comfort of their own home. Horses evoke a sense of peace and tranquility, as do dogs. It is no secret that visiting with animals is therapeutic.

Pushing for more oversight

Members of the Jewish community, as well as members of various professional organizations, are calling on the government of British Columbia to do more to regulate practising therapists and counselors in the province.

According to the Federation of Associations of Counseling Therapists in British Columbia (FACTBC), which is at the forefront of the campaign for this change, there is currently no regulatory body for counseling therapists in the province and, therefore, there are no regulatory standards for the work that counseling therapists do.

As it stands, they claim, someone can call themselves a mental health professional in British Columbia without having the checks that exist elsewhere in Canada. This, FACTBC points out, differs significantly from Ontario, Quebec and Alberta, which have all established regulatory bodies to oversee who can become a mental health professional. And, they add, the remaining provinces have done more than British Columbia when it comes to the consideration of implementing regulation.

A member of the Jewish community recently came to the Independent with her story. In her attempts to remove a social worker from her mother’s life, she encountered what she believes were numerous inadequacies within the present system regarding the protection of the public’s interest and confidence.

“When we seek the help of doctors and nurses, there is a protected title that tells us the person is qualified and safe and that there is a professional regulator to back up this promise,” she said. “Regulation protects people from harm. I cannot change the events of the past, but I can take from that experience and do what I can to ensure that all our citizens are protected, moving forward.

“I knew,” she added, “and had confirmed by other counselors and social workers that what this registrant was doing was in violation of their professional code. I saw my mother become further isolated from friends and family, while her health continued to decline both mentally and physically, while in this registrant’s care.”

The community member filed a complaint with the B.C. College of Social Workers (BCCSW). “Through this experience, I saw firsthand the lack of transparency in the complaint and discipline process that gives social workers the ability to enter negotiated complaint resolution agreements (CRAs) in exchange for keeping matters confidential. How can the public have confidence in regulators if the public is not aware of actions taken by regulators to protect them?” she wondered.

The community member then did what many who lack the financial means could not: she filed a civil claim against the social worker. She was not looking for money, she told the Independent; rather, she was looking for accountability and safety.

In the end, the woman and her family received an apology from the registrant and a promise to not repeat the following conduct: failing to differentiate between professional and personal boundaries; creating a situation of dependence with clients; and failing to limit their practice within the parameters of their competence.

“The college, in their inquiry decision, acknowledged that the time the registrant spent with my mother and the amount the registrant billed were not reasonable. I am not sure I will ever be able to fully reconcile with the events that occurred over a three-year span at the hands of a social worker, who was a friend at the time, and [that] I helped facilitate the introduction to my vulnerable, senior mother,” the woman said.

“To help with my own personal healing,” she added, “I elected to join FACTBC’s stakeholder table. I hope to lend my voice to ensure social workers, counseling therapists and emergency medical assistants who deal with our most vulnerable citizens are recognized as health professionals and regulated under the Health Professions Act.”

For Shelley Karrel of Jewish Addiction Community Services (JACS) Vancouver, the importance of regulation for counselors in British Columbia cannot be overstated. “For counselors working in the area of addiction and recovery, it is critical to know the importance of assessment, understanding the various stages of addiction, being able to identify the options available for treatment and recovery,” she said.

Karrel explained that understanding co-morbidity – i.e., the presence of one or more additional conditions – of mental health issues with addiction requires psychotherapists and counselors to have the proper training and education to know how to help clients deal with their various challenges.

“Having counseling fall under a regulated body will give clients the assurance they are dealing with qualified professionals who have to meet professional standards of practice, ongoing continuing education and clinical supervision,” she stated.

According to Glen Grigg, a Vancouver clinical counselor and the chair of FACTBC, “proper regulation will prevent consumers from harm. A consumer should not have to guess whether the therapist is equipped to deliver the services they promise. Moreover, when harm is done, it is important to know that a registrant’s college has the power to bring restoration and remediation when harm has occurred.”

FACTBC, which is comprised of 14 professional organizations that represent 6,000 mental health professionals in the province, is asking for safety and accountability. On professional title, it recommends one legislative authority and one coherent and fair process that prevents harm and has the power to act accordingly when harm has been done.

The B.C. government has said that it will first implement modernization of the health professions regulatory system – a step that FACTBC enthusiastically supports – and then give attention to the mental health system.

To Grigg, “this response comes down to saying, in effect, ‘despite the opioid crisis and mental health fallout from the pandemic, we can defer this issue.’ When pressed for what is intended after a new regulatory process is put into place, timeline unknown, the response is that government will ‘recommend’ that professions, such as counseling therapy and social work, become a ‘priority.’ A recommendation to a yet-to-be created bureaucracy falls far short of commitment and action.”

Grigg added, “FACTBC has been advocating for public protection where counseling therapy is concerned for more than 20 years and have heard, over and over, variations on the theme, ‘Yes, of course, we are going to protect the public, but later, at a time we’re not prepared to specify.’”

FACTBC does give the province credit for creating a Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions – a huge step forward, in their view, as was the $5 million the province put towards increasing mental health services. What the government needs to do to follow up on this momentum is to regulate counseling therapy, they assert.

At present there is no way of accurately ascertaining how many practising counselors there are in British Columbia. However, Grigg cites what Ontario discovered. In that province, in the time since they implemented statutory regulation on counseling therapists, they found that half the people providing services did not have any form of registration or certification.

“That’s dangerous,” said Grigg. “And we suspect that the situation in B.C. is similar but, because there is no central authority, even the scale of the problem is guesswork.”

He stressed, “It’s easy to see why this is so crucial. Suppose you were sick or injured and went to your local clinic or emergency department and discovered that it was up to you to figure out whether the people working there really were nurses and doctors, and whether they were qualified to provide care? That’s what people looking for counseling services are up against every day in B.C. There is no single title, like doctor or nurse or dentist or pharmacist, that identifies qualified and accountable counseling therapists.”

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.

Youth during the pandemic

Eleven months into the global COVID-19 pandemic and the statement, “we are living in unprecedented times,” has become commonplace and cliché. But, truth is at the root of this clichéd phrase. Finding and feeling our way through this new reality has been fraught with stark and opposing responses; from being immobilized and stuck, to being re-inspired and productive. As an educator and counselor who has been working with tweens, adolescents and adults in the community, I have witnessed both responses, or states of being, which are completely understandable and interchangeable as minutes turn into hours, as hours turn into days, as days turn over into weeks, and weeks turn into months.

For the purpose of this article, I want to focus on how the tweens and adolescents I work with have acknowledged that, while living life through COVID-19 is extremely tough, they have found, as the late Maya Angelou phrased it, “rainbows in the clouds” during this period. It is important to acknowledge the challenges youth face, such as experiencing restrictions to peer group interactions and experiencing the change of their schooling to remote learning. Further, an important yet more general challenge youth have faced is that the developmental stage these tweens and adolescents are in is typically punctuated by healthy detachment from their families and, in turn, usually is a period where more independence is fostered. This has been halted, interrupted and/or confused, as COVID-19 has demanded that youth are at home with their parents and families.

My overarching teaching and therapeutic philosophy is to meet the individual where they are. I try to listen to their spoken and unspoken language without handing out a quick fix. I am interested in how individuals, especially tweens and adolescents, connect with themselves as their lives have slowed down, as they have retreated to bedrooms, and in-person interactions and experiences have reverted to screens and the virtual world.

To facilitate a way into the interiority of my clients, I use the modalities of expressive arts therapies, contemplative writing and mindfulness practices. In the sessions I hold with them, they commiserate on how life is for them; grieving the smaller and larger losses and disappointments they have experienced; they freely use the session to rant and complain, and share their fears and anxieties. I then work with them in various creative and expressive modalities, which has enabled them to clarify, settle, discover and deepen a connection to their mind, body and heart.

Conducting expressive art exercises on secured video has been a poignant and immediate process. Using the shared-screen option, tweens and adolescents have been able to create and present their creations in real time. Expressive art therapies have encouraged self-discovery and enabled youth to access a range of emotions and insights that many of them did not even know they were experiencing. Engaging in exercises such as “what is in my heart?,” “draw a place,” “shape of me” (for which they can attach photos) have lowered stresses and anxieties, assisted in attention span and focus, and created an emotional uplift and emotional awareness. In these stressful, highly anxious times, expressive arts therapies have assisted greatly in calming, centring and linking youth to both their interior selves and the larger landscape of their lives, despite the uneasy and ongoing pandemic landscape.

Contemplative writing is a compassion practice that encourages one to write whatever the mind has to offer. It is a modality that helps to access who we are, what we need and what we want. It is an embodied practice that allows connection of one’s head, heart, body, breath and the page. Individual contemplative writing sessions have enabled youth to listen fully to themselves and the stories they need to tell and share. It has enabled youth to be listened to and, furthermore, to understand their own insights and often non-realized thoughts. I often tell my clients: tell your stories, I will hold your words and the spaces between them. The modality of contemplative writing has allowed youth to gain confidence and feel empowered, as they accessed and used their own voices, and overall experienced a sense of agency through their writing, telling and sharing of stories.

Throughout my sessions, in conjunction with expressive arts therapies and contemplative writing, I often employ various mindfulness practices. The general aim of mindfulness is also to connect with oneself. For tweens and adolescents, who are used to, even in COVID-19, a fast-paced, pop-up, manic existence with multiple devices in reach of their hands and gazes, mindfulness offers a sharp departure. The frenzied pace of day-to-day life often increases anxiety and depression in young people. It needs to be said that, often, the anxiety and depression is more of a low-grade malaise that we are unaware of until we begin to practise mindfulness.

Generally, mindfulness involves slowing down, delving into a deeper breath, noticing and following through into various practices to relax the mind and body. With tweens and adolescents, I also invoke the senses, encouraging them by carrying out exercises that use guided imagery and engagement of the five senses. This sensory engagement includes holding and touching various objects and taking time to peel and eat (taste) an orange. In the slowing down, in the distillation to being in the moment, in the focus of breath awareness and sensory awareness, I have found youth to become more relaxed, receptive and connected. Once they have practised mindfulness, it serves as a useful and cushioning tool whereby youth are able to calm and centre themselves as they navigate their day-to-day lives.

Dr. Abby Wener Herlin holds a doctorate degree from the University of British Columbia. She is the founder of Threads Education and Counselling and works with tweens, adolescents and adults. She carries out themed social justice and creative arts and writing workshops for students, teachers and schools. She is available for therapeutic sessions and contemplative writing workshops. She can be reached at [email protected] or via threadseducation.com. This article was originally published on health-local.com.

Uncovering the story within

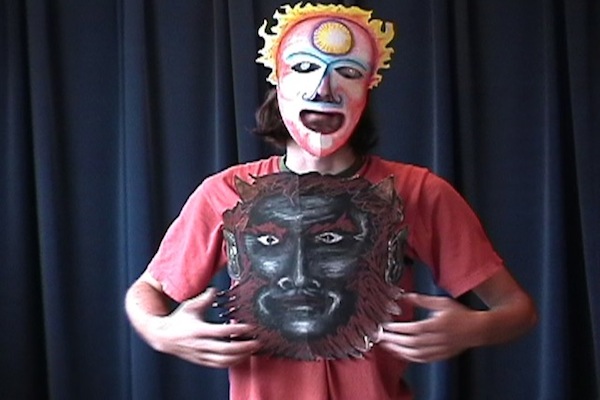

A participant in Yehudit Silverman’s The Story Within process shows off their self-made mask. (photo from Yehudit Silverman)

This past spring, Prof. Yehudit Silverman’s new book came out. In The Story Within: Myth and Fairy Tale in Therapy, the Concordia University professor emerita walks people through a step-by-step process to healing.

“When a person embarks on this journey, they feel called to a story, but they don’t know why,” said Silverman. “And it’s the sense of the unknown that’s really important…. Sometimes, in conventional therapy, we just go around in circles and might not necessarily get to the deeper layers that are inaccessible to us. But, through the arts and through the use of a character from a myth or fairy tale, gradually we can access those areas in ourselves.”

In Silverman’s approach, clients start by choosing their own story after going through a couple of exercises. “That process of choosing the story is therapeutic and healing in itself, because it’s part of the person’s sense of their own sense of knowing their own strengths and their own intuition, which is really important,” she explained. “Also, it’s important to stay with one character in a story for a long time, allowing the depth work to be done … recognizing what the character’s quest is, which is so important in myth and fairy tale, which is why I think they are still so relevant.

“The protagonist is on a quest and has to face obstacles and challenges,” she continued. “That can be so helpful when people are facing their own challenges and obstacles, so they don’t feel so alone. Also, they get to work with fiction, which is very safe, providing a certain amount of distance.”

People choose their stories for different reasons.

“Someone might be really drawn to a character that is having to do an impossible task, like in Rumpelstiltskin, where the girl has to make straw into gold,” said Silverman. “A lot of people think they are facing an impossible task, so they might then choose that story.

“Sometimes, it’s just the title of the story. I worked with an adolescent who was homeless and, sadly, addicted to drugs. When I worked with her, she chose the story of the handless maiden, which led to, sadly, to the revelation of her having been abused as a child. It was just the title that drew her.”

Once people choose a character, they start to build a mask. Then, they build the environment for the character and go through the steps that are described in Silverman’s book. The process is usually done within the context of a group, so that it is witnessed, which, according to Silverman, aids significantly in healing.

“They work with other people so that, at some point, they actually direct someone else in their mask and in their costume,” she said. “They get to look at what their character looks like to an outsider. And then, they have people embodying the obstacle and the helper, so they actually embody going through the quest and the challenges of the character.”

Silverman once worked with an anorexic teen who chose the character of Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz. “For her, the tornado was her eating disorder that took her to the Wonderful Land of Oz … which was, for her, magical. It was the ‘Land of Starvation’ and the good witch, Glenda, was actually evil for her, because she was trying to get her to go back to Kansas…. I realized that, for her, everyone in the hospital was evil, was going against what she felt was her sense of reality and her sense of what was magical and important, which was her starvation.

“And so, little by little, she worked with it and she embodied the tornado,” said Silverman. “She was actually swirling around and started crying, and realized how destructive it was. It was the first time she had had that realization – she didn’t have it when people were just talking to her.”

The teen connected and embodied the “chaotic energy of the tornado,” said Silverman. “She began to realize it was destructive and, then, she very slowly started healing. But, for her, having that story was essential.”

Although COVID-19 has made holding in-person group sessions impossible for Silverman, it has opened the door to including people from all over the world in the online groups she leads.

The Story Within outlines Silverman’s process step-by-step, taking readers through each one, and it can be useful for both therapists looking to implement the technique, as well as anyone wanting to understand why they do what they do.

The Story Within outlines Silverman’s process step-by-step, taking readers through each one, and it can be useful for both therapists looking to implement the technique, as well as anyone wanting to understand why they do what they do.

“If you’re going through something that is severe or you are in crisis, you should definitely see a therapist,” said Silverman. “And, if you’re going to use the book, you should only use it in context of therapy. But, for people looking for personal healing and a way to have creative reflection about what their life and quest is, then it is definitely for those people – for seekers, for artists and, also, for therapists, as something to integrate into their process with clients. And that’s something I do a lot of right now – supervising therapists insofar as how to integrate this into their work.”

Silverman said already established groups can use the book, as well, to form a more solid structural foundation perhaps. And, “there are so many people at home right now, and they are really questioning what their life is about,” she added. With the anxiety, she said, “having this structure, where they can go through a creative process … is so life-giving. It really allows us to express what’s going on inside into an outside form.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.

Want to be a therapist?

Avrum Nadigel’s latest book, which he co-authored with the late Dr. David Freeman, is aimed at people contemplating a career in family therapy. (photo from Avrum Nadigel)

Therapist Avrum Nadigel’s latest book hit the shelves this month. Co-authored with the late Dr. David Freeman, Where Would You Like to Start: A Master Therapist on Beginning Psychotherapy with Families is structured as a conversation or interview between veteran therapist Freeman and then-newish therapist Nadigel.

Nadigel is a family marriage therapist based in Toronto. Originally from Montreal, where he had worked for the Jewish community for years, he moved to Vancouver for a spell. It was here that he met Freeman (who passed away in 2010).

Freeman had brought in various therapists to speak on marriage, love and respect at different events. Attending these lectures, Nadigel found what the therapists had to say “redundant and I didn’t find it very helpful for me. I had a pretty severe case of fear of commitment, and they all rambled on about the same thing. But, when David spoke, it blew my mind.”

About a year after hearing Freeman speak, Nadigel met, online, the woman who would become his wife, Dr. Aliza Israel. “She is from Vancouver, but was staying in Toronto at the time,” said Nadigel. “Now, we’re married and have three kids. And that all started because of David’s talk in Vancouver. David’s talk introduced me to a type of therapy called family systems theory.’”

Nadigel read many books on the topic, including Freeman’s, which made Nadigel rethink his previously held suppositions about relationships and marriage. “I changed the way I practise with my own clients,” he said.

Nadigel moved to Toronto when he was accepted into a residency there. He started up a private practice and began to look for someone to mentor him. At his wife’s suggestion, he reached out to Freeman in Vancouver, who, although semi-retired, was happy to supervise Nadigel via Skype.

Nadigel recalled some of the game-changing ways in which Freeman changed his way of thinking.

“When I was single, if I felt anxious or not good in a relationship, I was taught that this meant there was something wrong,” said Nadigel by way of example. A relationship “should be lovely, giving and with good communication, but, as soon as I get anxious, I bolt. Then, David comes around and goes … ‘Perhaps your own internal states of anxiety have nothing to do with the people you’re dating, but with your own internal struggle itself.’ It really changed how I saw discomforting feelings in intimate relationships. It helped me sit with them longer.”

Thinking about his eventual marriage to Israel, Nadigel said, “I often think back to that time and think, ‘How did all this work?’ Maybe, it was one part luck, one part theory and one part having a good therapist in my corner.”

In addition to Freeman’s counsel, Nadigel has done much study on family systems, notably he did post-graduate training with the Western Pennsylvania Family Centre, which teaches Bowen family systems theory, as formulated by the late Dr. Murray Bowen, a psychiatrist and founder of the theory.

Recalling his conversations with Freeman, Nadigel said, “David was very worried about two things. Number one, that people were focusing too much on hacks and behavioural changes, and that the system was much more powerful than that … and that the system would often, not always, but often, thwart any attempts the individual would try to make the change. So, he was very concerned that there were so few therapists offering a larger perspective about human suffering.

“The second thing he was very worried about – I think this is because he was a grandfather at the time of his death, he had two grandkids – was about the disconnect from wise elders in society. I think that’s really coming home to roost right now, the fact that we have the hashtag on Twitter, where it says, ‘BoomerRemover.’

“Some people are thinking that, well, it’s good about this coronavirus – it’s going to kill off all the old people and there’ll be more condos. I don’t know what the hell they are thinking but we really do see the elderly as an inconvenience in a lot of cases, and David thought this creates an impoverished culture – that, when you think of traditional society, it’s the elders who share life lessons that can only be acquired over time, through adversity and history. You can read a book, but it’s very different if an elder tells you what it was like to survive the Blitz in Britain. And David thought that young people in their marriages were impoverished, because of their lack of connection.

“So, with those two things,” said Nadigel, “I thought, maybe, if I can somehow convince David to write another book, I could be the young green therapist and he could be the senior guy. He could speak to me and motivate the next generation of therapists.

“I thought to myself that it should be snappy and quick.… I threw him the idea and I think the same day he got back to me and said he thought the format’s viable – except that, in this case, it would be Skype calls between a young therapist and a senior therapist…. We quickly started working on this once a week.

“Then, David had the manuscript and was going on vacation,” said Nadigel. “We had a few more chapters to write; he really liked where the book was going. Then, I got an email from him, a very brief email, which was odd, because he was much more verbose. It just asked if I could call him.

“I thought, that doesn’t sound good, that maybe he was going to say the book sucks. I called, and it was his now-widow [Judith Anastasia], who answered, and she said, ‘Avrum, I’m sorry to tell you, but David died of a heart attack while we were cycling in Croatia.’ I couldn’t believe it. It was a crazy summer. My dad died, my son was born and David died.”

Several years later, with Anastasia’s blessing and to honour Freeman’s memory and work, Nadigel started to complete their book.

Several years later, with Anastasia’s blessing and to honour Freeman’s memory and work, Nadigel started to complete their book.

“The book gives you a taste of a master therapist, to experience the wisdom and thinking he brought to thousands of families and couples he’s worked with over 40 years,” explained Nadigel. “And, once you finish the book, you might feel it’s your responsibility now to go and further your training in this area.

“David’s life work was helping people understand that, if you want to do well with your own personal goals and struggles and gridlock, you have to understand what you’re up against,” said Nadigel. “And you don’t do that by just talking about your neurotransmitters and serotonin and dopamine, or meditation…. It’s about certain ways of the here and now, that you either distance or connect through relationships that are happening right now – that are happening with your mother, your father, your sister, your aunt, your cousin. The work is staring you right in the face right now.”

Family system coaching, consultation or therapy, said Nadigel, is based on “the theory and the road map of going back and reworking through some of the gridlock in your family. And those people who are successful at doing something and thinking differently [about] their problems with their relationships – siblings, spouse, kids, whatever – [are] bringing those successes to every relationship. And that does not happen in the clinician’s office.

“Also, this type of therapy understands that human beings don’t get into problems because of their thinking – they get into problems because they are flooded with feelings…. It tries to promote good thinking to balance out strong feelings, toward being a little more strategic in how you conduct yourself in your relationships.”

And Nadigel himself is an example of how the approach can work.

“I’ve often thought that, if I was reading about this book, the interesting angle I always found … is that I was a punk rock alternative musician in Montreal. I was commitment-phobic and really saw marriage and family, marriage considerably, as the death knell of all that’s good in life – [that it’s] boring and sucks the nectar out of a good life. Then, David comes along in Vancouver and he just creates a profound paradigm shift in me, and I have come to a wildly different understanding. I’ve become a marriage therapist myself, a father, all this kind of stuff, so a pretty fundamental transition.

“I was one of these people that, once upon a time, really had a strong distaste for the very thing I’ve embraced,” said Nadigel. “It really is all credit to this one little talk in Vancouver in the JCC. There’s hope there. It doesn’t take years and years. It could be a 50-minute talk.”

Nadigel has created a blog and podcast to support the new book. To access it, visit nadigel.com/start. Electronic and hard copy versions of Where Would You Like to Start are available at amazon.ca.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.

Using film school as therapy

From Ma’aleh School of Television, Film and Art, standing, from left to right, are Asher Lemann, David Cohen, Chanan Ariel, Ofir Shaer, Yosef Baruch Kalangel and Nachum Lemkus. Sitting, from the left, are Keren Hakak, Menachem Assaraf and Shalom Sarel. (photo from Ma’aleh)

When a major donor came to Neta Ariel, director of Ma’aleh School of Television, Film and Art, with an offer to provide scholarships as long as the students give back to the community, Ariel accepted the challenge.

“Ma’aleh is located in the centre of Jerusalem and, unfortunately, there are a lot of social issues,” Ariel told the Jewish Independent. “For example, lots of high school-age teens walk the streets or, during the night, use drugs and live on the streets. So, my students tried to help them – we knew a few of them, and we invited them to come to the school once a week for two hours in the afternoon to learn about film.”

The students at Ma’aleh became mentors, encouraging the teens to bring their own stories to life through the materials. Another group – comprised of immigrants from Ethiopia – also works with the students.

“Tell your story,” said Ariel of the most important aspect of the program.

“At the end of the year,” she said, “when we screened the movie for the group, teacher, friends … it was an amazing thing. They [had] left high school, or the family didn’t want them; they felt like they’re losers and didn’t have self-confidence. When we had the screening and their family or friends came, they really appreciated them. And the film gave them hope. We thought, the making of the film was not only fun, it was a teaching tool to uplift them and our students.”

Through learning how to film, from making personal connections and from telling their stories – which often included trauma or conflict, from rape, violence and negative treatment to gender or sexual orientation issues – they began to heal.

For most participants, it was their first encounter with therapy.

“Most of the time, at the end of the day, after the project was done, they shared with us that this is the first time they’d dealt with this,” said Ariel. “This was their way to tell the society, family or friends that this is their story and what I suffer from.”

From these beginnings, the school developed a curriculum for the program and, with each passing year, it has grown. Now, the school offers two such programs, focusing on how to use film as therapy and how to work together.

“You have a group of social workers and filmmakers,” explained Ariel. “Every week, they meet and work on the exercises we give them, and they work together to find a balance. It works well, the partnership. It’s amazing how the psychologist becomes a filmmaker and the filmmaker comes to understand psychology.”

Months after Operation Protective Edge, the school decided to host a group of bereaved mothers from the conflict, to determine if there was a way they could help.

They found ways of incorporating filmmaking into the process of mourning. At each meeting, they studied and focused on one aspect of filmmaking – lighting, filming, music, and so on. Once taught, participants were given an exercise to practise the skill. Then, they were given a camera and asked to practise filming.

“They didn’t tell them to make a movie about something specific,” said Ariel. “They gave them a task about something emotional. Most chose an aspect connected to the son they lost a few months ago.

“Then, we teach them how to write the script, how to do voiceovers, how to incorporate music. Automatically, most would think about their son or themselves and their fears. So, part of the meeting was talking about what we go through, and a lot of it was about creating things.

“At the end of the year, everyone together made a film called Saba. The main character in the movie is the grandfather, as all of them had mentioned their grandfathers, from time to time.”

Last year, the school opened a bereaved fathers group and found that, while they seemed to barely communicate in the classroom, they collaborated well outside of class. They put together what Ariel described as an “amazing movie” about their surviving kids.

“This is something the fathers said – that the kids at home blamed the parents, saying that, at home, they give a lot of time, attention and energy to something dedicated to the dead son … and [are] not taking care of them,” said Ariel. “Regardless of the age of the kids, in every house, they found it was the same situation. And, it was just amazing.

“Now, we are trying to open a group for grandparents … but, most of them, they can’t come, too hard for them, very far. So, I hope that … we’ll open another group for bereaved mothers … those who couldn’t come last time.”

While the main objective of Ma’aleh stems from a Jewish perspective, Ariel travels the world to introduce filmmaking and therapy to schools.

“Most of our students come from a Jewish Orthodox background … not all, but a lot of them,” said Ariel. “And, a lot of the subjects we touch on are connected to Jewish identity and our roots.”

At the time of her interview with the Independent, Ariel had just returned from the United States, where one of her stops was at a Christian school, where she spoke about how to best relay religious differences through film.

Apart from teaching, Ariel uses these trips to fundraise for the school and to keep in touch with filmmakers, mostly in Los Angeles.

“When they come to Israel, they help us, come to give a workshop at our school,” said Ariel. “We do projects together. Most importantly, we’re sharing our graduate movies with the world. A lot of institutions in Israel and America use them as education tools, cultural tools, and even, from time to time, to promote Israel.

“My goal is that this tool will be used for all kinds of populations. Many different kinds of groups can take care of themselves using this process.”

For more information, visit maale.co.il. The bereaved fathers’ short film can be seen at youtube.com/watch?v=uoNiQVSqhOw&feature=youtu.be.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.

Art therapy kits to families

United Hatzalah of Israel and Artists 4 Israel distributed art therapy kits to families in southern Israel and held a program that included visits by graffiti artists who worked with teens to paint neighborhood bomb shelters. (photo from United Hatzalah of Israel)

At the end of last year, 75 families from southern Israel received specialized art therapy kits, thanks to a new project organized by United Hatzalah of Israel’s Team Daniel initiative. In conjunction with Artists 4 Israel, the art therapy kits were distributed Dec. 8-10, along with a program showing parents how to use the kits with their children and visits by graffiti artists who worked with teens to paint neighborhood bomb shelters. Various art therapists also participated in the events.

Last summer, during Operation Protective Edge, a group of Chicagoans was touring the Eshkol region as sirens blared. These community members were so moved by their experience and, after hearing about the death of 4-year-old Daniel Tragerman, decided to raise money to help the region. Some 50 Chicago families established Team Daniel to fund the training, placement and equipment needed for 100 United Hatzalah medics to service southern Israel. The new kits are given directly to the families of these volunteers, who often run out on a moment’s notice to attend to rocket attacks and other local emergencies.

“Because these particular families are committed to saving lives as United Hatzalah medics, it was important to us that we give them a way to cope,” said Brielle Collins, Chicago regional manager for United Hatzalah. “Art is such a powerful tool to give to people who are recovering from war, stress and tragedy.”

The arts kit was developed by experts from Israel and the United States in the mental health field in collaboration with the nonprofit Artists 4 Israel. It is hoped that the “first aid kit for young minds” will combat the effects of trauma and eliminate the chances of PTSD by up to 80% through self-directed, creative play therapies.

United Hatzalah, a community-based emergency medical response organization, has been distributing the kits in a pilot program throughout Israel since July.

This week’s cartoon … Nov. 20/15

For more cartoons, visit thedailysnooze.com.

This week’s cartoon … Oct. 16/15

For more cartoons, visit thedailysnooze.com.