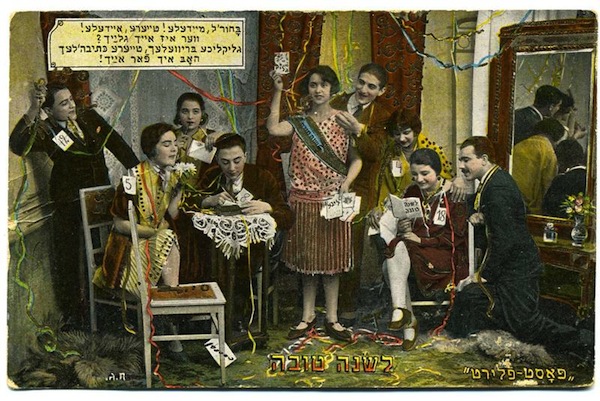

Rosh Hashanah greeting cards (above and below) from the author’s family’s collection. The cards are almost 100 years old. The translation of the one in which people are walking is “Into the synagogue.” It is signed by Chaim Goldberg, a well-known artist who also illustrated many children’s books. The party postcard, also done by Goldberg, is a printed rhyme, which translates as, “Boy, girl! Dear, refined! Who is like you? Happy letters, dear writings, I have for you!”

The Jewish calendar is an amazing conceptualization of time that has evolved (what else?) over time.

In his blog on the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot website, Ushi Derman relates that, originally, the Jewish calendar was a solar calendar. But it was not just a solar calendar, it was a holy solar calendar, delivered by angels to Enoch. (See the Book of Enoch, the section dealing with astronomy, called “The Book of Heavenly Luminaries.”) Temple priests had to follow a rigorous schedule – time itself was judged to be sacred. Thus, the Temple in Jerusalem was regarded as both the house of G-d and the dwelling of time.

With the destruction of Jerusalem’s Second Temple, the priests lost their power. They were no longer the mediators between G-d and the people. Authority switched to the scholars (our sages) of the Mishnah (edited record of the Oral Torah), Talmud and Tosefta (similar to the Mishnah, but providing more details about the reasons for or application of the laws).

In a bold move, the scholars declared that G-d had handed religious authority to humans. “Each month, envoys were sent to watch the new moon and to determine the beginning of the month. Thus, the ownership of time was expropriated from G-d and delivered to man – and that is why the Hebrew calendar has survived for so many centuries,” writes Derman in the 2018 blog “Rosh Hashanah: The Politics and Theology Behind Jewish Time.”

Here is a lovely story from The Book of Legends, edited by Hayim Nahman Bialik and Yehoshua Hana Ravnitzky, illustrating the above change. A king had a clock. “When his son reached puberty, he said to him: My son, until now, the clock has been in my keeping. From now on, I turn it over to you. So, too, the Holy One used to hallow new moons and intercalate years. But, when Israel rose, He said to them, until now, the reckoning of new moons and of New Year’s Day has been in My keeping. From now on, they are turned over to you.”

Perhaps oddly, the Mishnah mentions more than one new year. In fact, it points out four such dates on the Jewish calendar:

- The first of Nissan is the new year for kings and for festivals;

- The first of Elul is the new year for tithing of animals (some say the first of Tishrei);

- The first of Tishrei is the new year for years, sabbaticals and Jubilee, for planting and vegetables;

- The first of Shevat is the new year for trees, according to the House of Shammai, while the House of Hillel (which we adhere to today) says the 15th of Shevat, or Tu b’Shevat.

With its thrice daily prayers, the synagogue came to replace the Temple. Excluding Yom Kippur, synagogue attendance is higher on Rosh Hashanah than any other time of year. Rosh Hashanah prayers are compiled in a special prayer book, or Machzor.

Amid COVID-19, the following words about Rosh Hashanah have heightened meaning: “The celebration of the New Year involves a mixture of emotions. On the one hand, there is a sense of gratitude at having lived to this time. On the other hand, the beginning of a new year raises anxiety. What will my fate be this year? Will I live out the year? Will I be healthy? Will I spend my time wisely, or will it be filled in a way that does not truly bring happiness?” (See the Rabbinical Assembly’s Machzor Lev Shalem for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, published almost a decade ago.)

Amid COVID-19, the following words about Rosh Hashanah have heightened meaning: “The celebration of the New Year involves a mixture of emotions. On the one hand, there is a sense of gratitude at having lived to this time. On the other hand, the beginning of a new year raises anxiety. What will my fate be this year? Will I live out the year? Will I be healthy? Will I spend my time wisely, or will it be filled in a way that does not truly bring happiness?” (See the Rabbinical Assembly’s Machzor Lev Shalem for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, published almost a decade ago.)

Sounding the shofar is one of the special additions to Rosh Hashanah services. According to Norman Bloom – in a 1978 article on Rosh Hashanah prayers in Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought – the timing of the shofar blowing weighed in the physical safety and comfort of the congregation. Hard as it may be to comprehend today, scholars considered potential attacks from both local enemies of the Jews and from Satan himself. They also considered the comfort of the infirm, who might not be able to stay through a long service.

Rosh Hashanah has other curious customs. For example, there is a tradition of having either a fish head or, among some Sephardim, a lamb’s head as part of the Rosh Hashanah meal. This is meant to symbolize that, in the year to come, we should be at the rosh or head (on top), rather than at the tail (at the bottom). Vegetarians and vegans substitute a head of lettuce.

Both Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews have Rosh Hashanah seder traditions. The symbolic foods include beets, leeks, pomegranates, pumpkins and beans. As Rahel Musleah has pointed out, each food suggests a good wish for the coming year. Thus, before eating each one, people recite a special blessing. Humour is at play, too, as some of the blessings are puns on the food’s Hebrew or Aramaic name. (Read Musleah’s article “A Sephardic Rosh Hashanah Seder” at myjewishlearning.com/article/a-sephardic-rosh-hashanah-seder.) Of course, we cannot neglect to mention that the festive table also includes apples dipped in honey, for a sweet new year, and a round challah, symbolizing both the cycle of life and G-d’s kingship.

Another Rosh Hashanah custom is Tashlich. This ceremony involves going to a body of water to symbolically cast off one’s sins. Breadcrumbs are often used, as are leaves, but, seeing that COVID-19 will be a part of this year’s holiday, here is another suggestion. Originally, this activity was used with youth groups of the Reform movement – participants wrote out their sins and then the papers on which they were written were put through a paper shredder. A dramatic gesture, suited to our current need for social distancing.

My city, Jerusalem, is a land-bound city without a sea or lake in its immediate vicinity. So, what do residents of the capital do? Those who wish to practise Tashlich go to one of the following four sites. Two of the four places are near the Supreme Court: the Jerusalem Rose Garden and the Jerusalem Bird Observatory. Also in the same general area is the Botanic Garden in the Nayot neighbourhood and, in the Old City, one can go to the Shiloah Springs in City of David.

Wishing all readers a year of blessings and not of curses.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.

* * *

Additional observations

• Hebrew has a number of expressions using the word rosh. Here are just a handful of examples: rosh hamemshala (prime minister); rosh kroov, literally cabbage head, or a negative reference to someone who is not very bright; rosh katan, someone who is small-minded; l’kabel barosh, to be defeated; and rosh tov, or good vibes.

• Anyone interested in learning more about the solar calendar should read Prof. Rachel Elior’s article, “Enoch Son of Jared and the Solar Calendar of the Priesthood in Qumran,” which can be found in a Google search.