A model of the Kaifeng synagogue at an exhibit at the Diaspora Museum in Tel Aviv in 2011. (photo by Sodabottle via commons.wikimedia.org)

With the Chinese New Year taking place next week, it is an appropriate time to reflect on the close and positive relationship between Jewish and Chinese peoples, which reaches back almost 2,000 years.

It might be simplest to begin with the fall of Jerusalem to the Romans in the year 70 of the Common Era. This was the climax of the first of three Jewish-Roman wars that would take place over the first and second centuries. The net result of these conflicts was the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Jews, the enslavement of many others, and those who managed to escape such tragedies fled as refugees. This scattering of Jews across the world we call the Diaspora ultimately resulted in the formation of the various communities we are familiar with today, such as the Ashkenazi, Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews. But there was a smaller, lesser-known Diaspora community that settled in China.

Between 206 BCE and 220 CE, China was ruled by the Han Dynasty. The Han established a vast international trading network that came to be known as the Silk Road. According to the oral history of the Chinese Jews, their ancestors first settled in China during the late Han Dynasty. Such a period would correspond with the Diaspora that followed the Jewish-Roman wars.

After the collapse of the Han Dynasty, the Silk Road trading network collapsed, but was reestablished in 639 CE during the Tang Dynasty. The Silk Road interconnected Tang Dynasty China with the wealthy states of India, East and North Africa, across Asia and into Europe. During the Medieval period, many Jews made their living as merchants. At this time, Christians and Muslims refused to trade directly with each other, and Jews earned great profits acting as intermediaries.

Many Jews traded along the Silk Road, the most prominent group of whom were the Radhanites, who inevitably found themselves in China. It is during this period that the first document indicating the presence of Jews in China has been found. It describes how a rebel leader executed foreign merchants and Jewish residents in the city of Guangzhou. Discovered at an important stop along the Silk Road in northwest China, the document dating to some point around the eighth or ninth centuries was written in a Jewish-Persian script on paper, which at the time would have only been available in China. Some historians have suggested that the Radhanites were responsible for bringing Chinese paper technology to Europe, although this theory is contested. The presence of Jews in Guangzhou at this time should not be surprising, considering it was an important port city linking Chinese and Middle Eastern trade. Guangzhou has one of the oldest mosques in the world and, at the beginning of the ninth century, may have had a population of as many as 100,000 foreigners.

In 908 CE, the Tang Dynasty fell, the Silk Road trading network again collapsed for several centuries and the prominence of the Radhanites declined. But this did not mean the end of the Jewish presence in China. Between 960 and 1279 CE, China was ruled by the innovative and prosperous Song Dynasty, with their capital city at Kaifeng. Kaifeng has been described as the New York of its day. It was a massive cosmopolitan city, a centre of global trade and the largest city in the world, reaching a population of 1.5 million people.

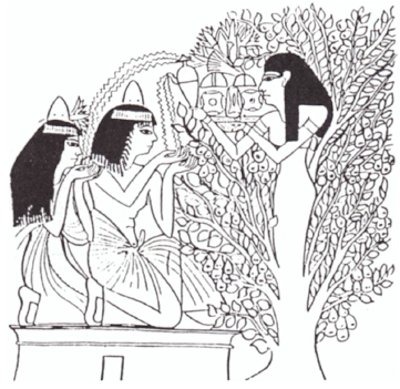

Though Jews would settle in other cities, such as Hangzhou, Ningbo, Ningxia and Yangzhou, most were in Kaifeng, and it became the centre of Chinese Jewry. The first synagogue was built in Kaifeng in 1163 CE. It was made of wood, in a Chinese architectural style. It would be destroyed and rebuilt many times throughout its history. The Jews of Kaifeng were held in high esteem by the Song emperors, and went on to pursue successful careers not only as merchants, but as court officials, scholars and soldiers. There is still a Kaifeng Jewish community today.

In the early 12th century, the first Jin emperor, Wanyan Aguda, unified the Jurchen, a group of tribal peoples living in Manchuria. The Jurchen waged war against the Song Dynasty and, in 1127, Jurchen forces conquered Kaifeng, an event that has come to be known as the Jinkang Incident. After this battle, the Song capital was moved south to Hangzhou, and many of the Kaifeng Jews accompanied the Song rulers in their migration. Nevertheless, there were some who stayed in Kaifeng. The Jurchen established the Jin Dynasty, and continued to wage war against the Song Dynasty for more than 100 years. Eventually, both the Jin and the Song were conquered by the Mongols in the 13th century.

In 1232, the Mongols besieged Kaifeng. During the conflict, the Jin used rockets against the Mongol invaders, which is the first use of rockets in warfare in recorded history; a technology all-too-familiar to the modern residents of Israel. In the mid-14th century, the Mongol rulers of China established the Yuan Dynasty, with their capital in Beijing. When Marco Polo traveled to Beijing in 1266, he wrote about the importance of Jewish merchants there.

In 1276, the Mongols conquered the Song capital of Hangzhou. In 1280, the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, issued a decree banning Jews from kosher practices and circumcision. Yuan Dynasty documents written in 1329 and 1354 issue a request of Jewish residents in China to go to Beijing to pay taxes. Though many atrocities occurred during the Mongol invasions, their rule was nevertheless marked by flourishing trade and the Jewish communities of China persisted.

At the site of the synagogue in Kaifeng, several stone steles have been recovered. The oldest, written in 1489, commemorates the construction of the synagogue in 1163. It describes how the Jews first entered China during the late Han Dynasty, and the Jinkang Incident, including how many of the Jewish population of Kaifeng fled to Hangzhou. Also inscribed on this stele were the following words: “The Confucian religion and this religion agree on essential points and differ in secondary ones.”

A second stone stele was made in 1512, which describes Jewish religious practices, which is fascinating considering it is written in Chinese. In 1642, a third stele commemorated the reconstruction of the synagogue in Kaifeng after it was destroyed by a flood. The synagogue was destroyed again by a flood in 1841, but was not rebuilt. This is likely due to the sociopolitical turmoil occurring in China at the time. It is interesting to note that, while Jews were persecuted, rejected and alienated by the nations of Europe, they were accepted and assimilated into Chinese culture.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, persecution of Jews in Europe began again on a massive scale. The worst events of these times were the many pogroms in the Russian Empire, where hundreds of thousands of Jews were murdered, raped, robbed. Many Jews were forced to flee as refugees, some migrating to North America, some to Palestine, and some to China. The Russian Revolution in 1917 resulted in the deaths of around 250,000 Jews, and the orphaning of around 300,000 Jewish children. Many Russian Jews fled to the city of Harbin, in Manchuria, whose Jewish population reached 20,000. However, when the Japanese annexed Manchuria in 1931, many among that population left for Shanghai, Tianjin or Palestine.

Many Chinese intellectuals understood the plight of the Jewish people, and compared it to their own. The Chinese Nationalist and founder of the Republic of China, Dr. Sun Yat-sen, made the following comparison: “Though their country was destroyed, the Jewish nation has existed to this day…. Zionism is one of the greatest movements of the present time. All lovers of democracy cannot help but support wholeheartedly and welcome with enthusiasm the movement to restore your wonderful and historic nation, which has contributed so much to the civilization of the world and which rightfully deserves an honorable place in the family of nations.”

During the course of the Second World War, the Jewish population in China would swell to 40,000, many of whom resided in Shanghai. A number of Chinese diplomats helped smuggle in Jews using special protective passports. One such hero, a Chinese diplomat working in Vienna named Ho Feng Shan, helped Jews from Nazi-occupied Europe get to China, ultimately saving around 3,000 lives. Ho Feng Shan was posthumously awarded the title Righteous Among Nations by Yad Vashem in 2001.

In 1943, the Japanese forced the 20,000 Jews living in Shanghai into a ghetto that was around one square kilometre in size, with conditions described as squalid, impoverished and overcrowded. The Shanghai ghetto was also inhabited by some 100,000 Chinese residents.

The Nazis pressured the Japanese to execute the 40,000 Jews living in China, but the Japanese purposefully delayed the planned atrocity, ultimately saving the Jews’ lives. When the Japanese military governor of Shanghai informed the leaders of the Jewish community of the planned execution and asked them why the Germans hated them, one rabbi responded by saying “because we are short and dark-haired,” a reply that allegedly caused a smile to appear on the serious face of the governor. After the war, most of the Jews in China migrated to the newly formed state of Israel.

Ben Leyland is an Israeli-Canadian writer, and resident of Vancouver.