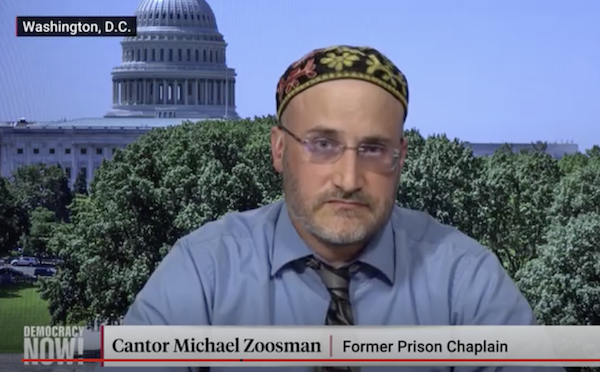

L’chaim! Jews Against the Death Penalty co-founder Cantor Michael Zoosman on Democracy Now! with Amy Goodman on Aug. 2, 2023, reiterating L’chaim’s opposition to the death penalty for the Pittsburgh Tree of Life synagogue shooter – and in all cases. (screenshot)

Recently, the American TV show Democracy Now! with Amy Goodman approached me in my role as co-founder of L’chaim! Jews Against the Death Penalty – which has roughly 2,700 members worldwide – to explain our opposition to the death sentence that the U.S. federal government issued for Robert Bowers, the perpetrator of the Pittsburgh Tree of Life shooting on Oct. 27, 2018. This was the deadliest antisemitic attack in American history and a crime of unspeakable horror that took the lives of the 11 Tree of Life martyrs, z”l.

My journey to becoming L’chaim’s co-founder was a direct result of my service as the cantor of Vancouver’s Congregation Beth Israel from 2008 to 2012. During my time at BI, that wonderful kehillah granted me the opportunity to serve as an agent of the Canadian government as Jewish prison chaplain for the 11 federal prisons within the Pacific region of Correctional Service Canada, which I did from 2009 to 2012. That experience was integral in the formation of my stance as a firm opponent of capital punishment in every case. During my years in that position, I got to know many individuals whose crimes might have qualified them for the death penalty in various states or federally in the United States. I saw firsthand how many of these individuals changed, while they remained incarcerated.

Since 2020, L’chaim’s members and I have been in touch with all individuals with active execution warrants in the States, as well as all Jewish men and women on American death rows. This includes my longtime penpal Jedidiah Murphy, a Jewish man with dissociative identity disorder who is the next human set for execution by Texas. The Lone Star State – the most prolific state killer in the United States – plans to kill Jedidiah on Oct. 10, which is World Day Against the Death Penalty. To do so, Texas will use the most common American form of execution, which is lethal injection.

Lethal injection was first implemented in this world by the Nazis as part of the Aktion T4 protocol used to kill people deemed “unworthy of life.” That protocol was first devised by Dr. Karl Brandt, the personal physician of Adolf Hitler. Every use of lethal injection carries on this direct Nazi legacy. This is the method by which the federal government likely will put to death Robert Bowers. Various states employ gas chambers to put their inmates to death, with Arizona even offering Zyklon B, as used in Auschwitz.

The members of L’chaim who, like me, are direct descendants of Holocaust survivors, know very well that the death penalty is not the same as the Shoah. And yet, members also know the dangers of giving a government the power to kill prisoners. Holocaust survivor and human rights activist Elie Wiesel articulated this most prophetically when he famously said in a 1988 interview: “With every cell of my being and with every fibre of my memory, I oppose the death penalty in all forms…. I don’t think it’s human to become an agent of the angel of death.” He later added of capital punishment: “death should never be the answer in a civilized society.”

There are no exceptions. For Wiesel, Martin Buber, Gershom Scholem, Nelly Sachs and other Jewish human rights activists in the wake of the Shoah, this included staunch opposition to Israel’s execution of Nazi perpetrator Adolf Eichmann, which Buber called a “great mistake.” For the thousands of members of L’chaim! Jews Against the Death Penalty who carry this torch, the mistake applies as well to Robert Bowers.

In his “Reflections on the Guillotine,” Albert Camus concluded: “But what then is capital punishment but the most premeditated of murders, to which no criminal’s deed, however calculated it may be, can be compared?” From my personal experience in communicating daily over email, letters and phone with condemned men and women counting down their final months, weeks, days and hours, I can attest to this psychological torture. I can confirm that there is no humane way to put prisoners to death against their will.

The death penalty condemns the society that enacts it infinitely more than the human beings it condemns to death. Canada realized this decades ago, when it abolished the death penalty. The west African nation of Ghana was the latest country to join Canada as an abolitionist nation, just weeks ago, during the Tree of Life capital trial. I pray that, one day, the United States will join Ghana, Canada and the more than 70% of world nations who stand against the consummate human rights violation that is capital punishment.

For those who remain unconvinced, as I was before I became a prison chaplain, consider the words of the late Jewish U.S. Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, the namesake of my alma mater. In his dissent for a renowned 1928 case, Brandeis wrote: “Our government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example. Crime is contagious.”

When the government imposes and then carries out a death sentence, it teaches everyone that unnecessary lethal violence is an appropriate problem-solving tool. Pittsburgh resident and death penalty abolitionist Fred Rogers (children’s educator and entertainer Mister Rogers) recognized this when he said of the death penalty “it just sends a horribly wrong message to children.” In every single case, state-sponsored murder under the disproven pretence of deterrence is not an appropriate tool to punish an offender who is no longer a threat behind bars. As Brandeis and Wiesel knew: the government should set a moral and ethical example.

The ruling in favour of state killing perpetuates the cycle of violence. It leaves the door open to the man-made Angel of Death – a door that allowed the United States to execute a severely mentally ill prisoner in Missouri on Aug. 1 and a prisoner “volunteer” for state-assisted suicide in Florida on Aug. 3. The United States was joined that week by Iran, which executed 12 human beings. The previous week, Singapore hanged a man and a woman for drug charges, and Bangladesh hanged two other human beings.

America – and human civilization – must do better. If not, the Pandora’s box of death can lead to what the world has seen with the execution of political protesters in Iran, the recent “kill the gays” law passed in Uganda, which allows execution for homosexual sex crimes, and the calls for the death penalty for abortion, which at least four American states have proposed since the overturning of Roe vs. Wade.

Let there be no doubt that those immediately impacted by the Pittsburgh shooting – including surviving family members – have been divided in their attitudes about the death penalty for the shooter. On a congregational level, two of the three targeted synagogues within the Tree of Life building have asked the federal government not to pursue the death penalty. This includes Dor Hadash, which hosted leaders in L’chaim for a program to help their community mobilize to abolish the death penalty. Still, quite understandably, most immediate family members indeed advocated death for the shooter. Far be it from me or anyone to judge them for how they feel. As a hospital chaplain, I regularly counsel mourners that, when grieving, they should be allowed to feel the full gamut of human emotion, including rage, and even the desire for vengeance where applicable. Any civilized society has a responsibility to protect and honour all such mourners, while simultaneously upholding the fundamental human rights upon which the world stands. Most basic to these, of course, is the right to life.

May Americans and Jews everywhere honour the victims of Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life – Eitz Chaim in Hebrew – by reaffirming the sanctity of life. Instead of more killing, may they follow the example of the inspiring Jewish community of Pittsburgh. Earlier in the week before the verdict of death, in what was but the latest example of that community’s unflagging proverbial steel resolve, it hosted a life-affirming parade to celebrate the dedication of a new Torah – known also as an Eitz Chaim – in loving memory of Joyce Fienberg, z”l, one of the 11 Tree of Life martyrs, and her late husband, Dr. Steven Fienberg, z”l. That sacred community once again has brought new life to the exhortation that has motivated Jewish people for millennia: “Am Yisrael chai,” “The people of Israel live.”

To this profound demonstration of the very best of Jewish values and resilience, I fervently add the resounding response to the Tree of Life verdict from the thousands of members of L’chaim! Jews Against the Death Penalty, chanting “l’chaim!” – “to life!”

The Democracy Now! TV interview ended with a video clip of the El Maleh Rachamim for the 11 Tree of Life martyrs that I chanted in front of the U.S. Supreme Court while the trial was taking place, as part of the Annual Fast and Vigil to Abolish the Death Penalty. No matter where TV viewers and readers stand on the death penalty, it is most appropriate for that memorial prayer for the victims to be the final words here.

Zichronam livracha, may the beloved memories of the 11 Tree of Life martyrs be for an everlasting blessing.

May their neshamot / spirits be loving guides for us all.

May their loved ones be comforted among all the mourners of Zion and Israel from a grief the likes of which most human beings like me never could begin to fathom.

May the killings end.

Cantor Michael J. Zoosman, MSM, BCC, served as cantor of Congregation Beth Israel 2008-2012 and as Jewish prison chaplain for Correctional Service of Canada, Pacific Region, 2009-2012. He is the co-founder of L’chaim: Jews Against the Death Penalty and an advisory committee member of Death Penalty Action.