For us to become a glowing menorah, casting light in and around us, and lighting up the world, we must be oil-like. (photo from Cinco Resources, Inc.)

The story of Chanukah takes us back to the year 164 BCE, two centuries before the destruction of the Second Holy Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans. Then, Israel was under the rule of the empire of Alexander the Great.

The Greeks, in the year 200 BCE, had a great impact on the civilization of the whole world and the Jewish people. Although the Jewish people were very strong spiritually, they were very weak politically and militarily. The spiritual strength was attributed to the men of the Great Assembly; great sages and their successors, the Tannaim (codifiers of the Mishnah). When Alexander the Great of Macedonia conquered the civilized world, he brought the Greek culture, language, thoughts, beliefs, philosophy, customs and modernization to the masses and these beliefs rapidly spread.

When Alexander conquered Palestine, he gave complete freedom of religion to the Jews. He abolished taxes on the Sabbatical year, when the Jews didn’t work the land. As well, he freed Jewish soldiers from duty on the holy Sabbath. Alexander the Great died at the young age of 33. After his death, Jewish nobility and upper classes began taking on Greek ideas and customs. Would you even guess that the words synagogue and sanhedrin (supreme Jewish court) are Greek words?

Greek culture, aka Hellenism, began to make a serious impact on Jewish life in the Holy Land. The great rabbis of the generation saw the dangers of the Hellenists, threatening the traditions and faith of the Jewish people and the Torah. Hellenists were springing up everywhere.

Eventually, King Antiochus Epiphanes set out to destroy the last remnants of the Jewish people. He decreed the death penalty for any Jew found abiding by the laws of Torah, for observing the Sabbath and holy days, for the reading and teaching of Torah or gathering in houses of prayer. The building of the Beit HaMikdash, the Jewish Holy Temple in Jerusalem, was changed officially into a temple for the highest Greek god, Zeus, and an idol was set up before the holy altar. Altars were also erected for the Olympian gods, and there were heathen altars. The king’s soldiers forced Jews to bring offerings to these idols and bow down to them in the cities.

The study of Torah was not only forbidden, but the Torah scrolls were destroyed and their owners burned at the stake. Parents who circumcised their children were killed and teachers of Torah were tortured for trying to perpetuate the forbidden Jewish religion.

King Antiochus had no idea that his attempt to eradicate the Jewish religion would have just the opposite result. Many Jews became strengthened in their faith. When they came to the city of Modiin, Mattityahu, the father of the Maccabees – named for the verse in Exodus (15:11), “Who is like you of the lords of Israel” – came out and killed a traitor who was offering sacrifices to a Greek god.

His experience inspired many miraculous victories, including the large military victory over the Greeks in the year 3622 (139 BCE). Thereafter, the enemy was cleared out of the land, and Jerusalem and the Holy Temple were liberated. The victorious Jews set out to destroy the idols and altars in the Holy Temple and the golden menorah was replaced with an iron-wrought one. This took place on the 25th of the month of Kislev and the rededication of the Holy Temple lasted for eight days, until more oil could be made and brought to Jerusalem.

One small bottle of olive oil with the high priest’s kosher stamp on it was found, which was just enough to last for one day and yet, miraculously, it lasted for eight days and the entire dedication ceremony, being used to light the menorah again in the Holy Temple daily. The prayer “Al HaNissim” – about the miracles – is recited in the Grace After Meals and also the Amidah prayer during Chanukah and recalls the many miracles that took place.

Judaism and Jewry were undoubtedly saved from one of the greatest dangers that ever threatened the existence of our people. It was a struggle not only of the few over the many, but of the holy versus the unholy and of Judaism and Torah over Hellenism. The forces of the Torah prevailed.

Why do we celebrate so much about the oil? The miracle of the oil would seem of minor significance relative to the military victory of the Jews. Had the Jews been defeated by the Greeks, there would be no Jews today, G-d forbid. If the oil wouldn’t have burned for eight days, the menorah wouldn’t have been kindled. Why then, is the main focus of Chanukah on the oil?

Many insights have been offered. A symbolic explanation follows that shows how oil has the same characteristics as a person. This is based on a letter written by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, of blessed memory, before Chanukah 1947.

In writings of Jewish mysticism, all physical properties of an object are seen as continuations of their metaphysical properties. Every object originates in the realm of the spirit, embodied by a particular sublime energy. The energy evolves to assume a physical reincarnation, giving rise to particular physical characteristics that mirror their spiritual source. This is how a person ought to behave in their life. This, parenthetically, constitutes an extremely rich component of Judaism.

From the vantage point of Torah, the truths of science, physics, chemistry, biology, etc., and the truths of philosophy, spirituality and psychology, are merged together in a perfect mosaic, since all that is physical has a realm in the spiritual.

Olive oil contains four interesting qualities:

1. It is produced by crushing and beating ripe olives. The olive must be severely “humbled” and pressed to emit its oil.

2. Olive oil penetrates solid substances deeply – as do many other oils extracted from minerals, plants and animals. We know how difficult it can be to remove oily grease from our fingers and clothes. Oils have been used throughout history as remedies for bodily wounds, since oil penetrates the body far beyond its external tissue.

3. Oil does not mix with other liquids. When you try to mix oil with water, the oil remains distinct and will not dissolve in or combine with the water.

4. Not only will oil not dissolve in water, it rises and floats on top of other liquids. On a symbolic level, this appears paradoxical. Is oil humble or arrogant? It gets beaten badly, yet rises to the top.

These four qualities displayed by oil are essentially a physical manifestation of four spiritual and psychological attributes from where oil originates.

In our lives, we may attempt to become “oil-like.” How? By learning how to cultivate the four properties that characterize oil.

1. The crushing and pressing of the olives into oil represents the notion of humility. Seeing ourselves for who we really are, being open to discovering our biases, blind spots and errors, allows us to genuinely grow.

2. The direct result of this “pressing” is our ability to become oil-like, and affect others deeply. We can share ourselves with others and be in a real relationship. It takes courage to show up in the world with the “real you” and to then connect with other hearts profoundly.

3. Humility and genuine relationships must never allow one to be pulled down completely and dragged down emotionally. One must not forfeit their individual identity. The beauty of a relationship is the fact that two distinct individuals choose to share themselves with each other. Just like oil, you know how to feel and experience another human being meaningfully, while not becoming consumed by the other’s identity.

4. This threefold process of crushing yourself, bonding with others and at the same time retaining your distinctiveness, should ultimately cause you to rise, just like oil, to the top, and “float” above all that is around you. Realizing that you are a “piece of the Divine” (Tanya, Chapter 2) and that every moment you are a representative of G-d to our world, allows a person to experience themselves as indestructible, and wholesome. This comes not from arrogance, but from realizing that one’s soul is part of the infinite.

This is the deeper mystical significance of the miracle that caused the oil to last beyond its one day. It is also why we celebrate with a focus on oil, as this story captures the rhythm of our lives. For us to become a glowing menorah, casting light in and around us, and lighting up the world, we must be oil-like.

First, we must discover the art of humility and integrity; second, we must allow ourselves to show up genuinely in our relationships; third, we must retain our distinctiveness and individuality; and fourth, we must always recognize that part in us which is always “on the top.”

Judaism, particularly its festival of Chanukah, comes to teach ordinary human beings how to become oil-like. If we wish to ignite a heavenly radiance in our lives, we ought to take a good and deep look at the olive oil in our menorahs.

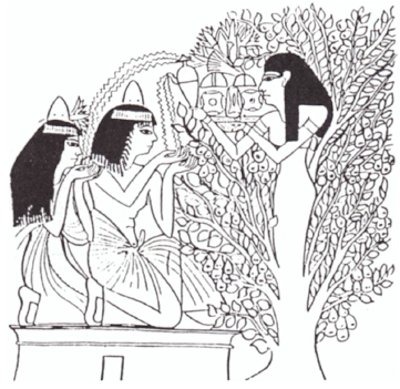

In that sense, oil embodies the essence of Chanukah, the Festival of Lights. Indeed, in many a Jewish household, the Chanukah lamps consist of wicks dipped in olive oil, replicating the Temple menorah lamps. Throughout the holiday, to commemorate the miracle of the oil, we eat various foods cooked in oil, including such delicacies as latkes and sufganiyot.

The following is a story I read recently.

In Brooklyn, N.Y., there was a Jew named Yankel, who owned a bakery. He told the story of how he survived the Holocaust. He said, “You know why it is that I’m alive today? I was just a teenager at the time. We were on a train, in a cattle car, being taken to Auschwitz. Night came and it was freezing, so deathly cold in that cattle car. The Germans would leave the cars on the side of the tracks overnight, sometimes for days on end without any food, and, of course, no blankets to keep us warm.”

Yankel continued, “Sitting next to me was an older Jew – this beloved elderly Jew – from my hometown. I recognized him but had never seen him like this. He was shivering from head to toe and looked terrible. I wrapped my arms around him and began rubbing him to warm him up. I rubbed his arms, legs, face and neck. I begged him to hang on. All night long, I kept the man warm this way. I was tired, freezing cold, my fingers were numb, but I didn’t stop rubbing the heat onto this man’s body. Hours and hours passed this way. Finally, night passed, morning came and the sun began to shine. There was some warmth in the cabin, and then I looked around the car to see some of the other Jews in the car. To my horror, all I could see were frozen bodies, all I could hear was deathly silence.

“Nobody else in the cabin made it through the night – everyone had died from the frost. Only two people survived: the old man and me. The old man survived because somebody kept him warm; I survived because I was warming somebody else.”

Yankel’s life was saved by and for assisting another human being.

When you warm other people’s hearts, you automatically warm yourself. Humans need each other and get elevated by helping and supporting others. When you seek to support, motivate, encourage and inspire others, then you discover support, encouragement and inspiration in your own life as well.

This is the lesson of the olive oil: to penetrate and make a difference in humanity and, in turn, this will empower us to do more, like the light of Chanukah, which increases every night of the festival. Beginning with one candle with its small flicker and increasing every night by adding one more candle, until the menorah shines its eight lights in total splendor and beauty.

May G-d help us celebrate this Chanukah with real peace in Israel and around the globe, and bring us the ultimate refinement of the world with the imminent coming of Mashiach. Then, we will all merit to light our Chanukah lights in the third Holy Temple in Jerusalem, the most beautiful and everlasting one.

Wishing everyone a joyous festival of Chanukah and a fabulous time with family and friends eating delicious latkes and doughnuts, playing dreidel and singing Chanukah songs. Chag sameach!

Esther Tauby is a local educator, writer and counselor. She offers many thanks to her husband, Rabbi Avraham Tauby, for his help with research for this article.