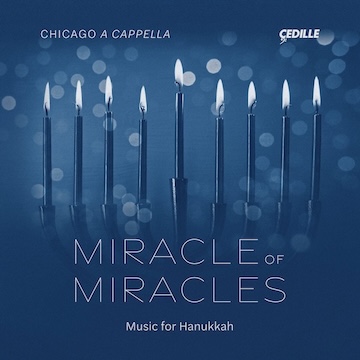

Chicago a cappella in June 2022. The ensemble released Miracle of Miracles: Music for Hanukkah last month. (photo by Kate Scott)

The CD Miracle of Miracles: Music for Hanukkah arrived at the Jewish Independent unsolicited. The album, released last month by Cedille Records, features a range of songs from the American Jewish musical tradition, performed by Chicago a cappella vocal ensemble. As someone who spent a good portion of her teenagehood in a choir at a Conservative synagogue and about a decade singing in another Conservative synagogue choir later in life, I have been happily singing along to this recording, enjoying the fresh take on songs with which I am mostly quite familiar.

Miracle of Miracles will appeal most, I think, to someone like me, who grew up in a Conservative Judaism milieu where a cantor and choir formed a large part of the service, or someone who appreciates classical music, as Chicago a cappella are classically trained A-listers, who perform a repertoire of music from the ninth to the 21st centuries. The current artistic director is John William Trotter, and Miracle of Miracles was recorded over a few days last January at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago.

The CD opens with an arrangement of “Oh Chanukah / Y’mei Hachanukah” by Robert Applebaum that the liner notes describe as “modern versions of the song form from the confluence of at least two streams, the first springing from Hebrew lyrics, the second flowing together from Yiddish and English sources. Turning again to [composer] Harry Coopersmith’s mid-20th-century collection … to create something of a mash-up of ‘Oh Chanukah’s’ popularity.”

The CD opens with an arrangement of “Oh Chanukah / Y’mei Hachanukah” by Robert Applebaum that the liner notes describe as “modern versions of the song form from the confluence of at least two streams, the first springing from Hebrew lyrics, the second flowing together from Yiddish and English sources. Turning again to [composer] Harry Coopersmith’s mid-20th-century collection … to create something of a mash-up of ‘Oh Chanukah’s’ popularity.”

There are several Applebaum arrangements. His “Haneirot Halalu” (“These Lights We Light”) mixes English translation and commentary into the traditional Hebrew lyrics, and his “Maoz Tzur” is a cantor-choir interplay that comprises elements most of us will recognize and be able to join initially, but then becomes more complex. His finger-snapping arrangement of Samuel E. Goldfarb’s well-known “I Have a Little Dreidl” – called “Funky Dreidl” – is in English with the Hebrew “nes gadol haya sham,” “a miracle happened there,” as a kind of chorus. It’s followed on the CD by a lively rendition of Mikhl Gelbart’s Yiddish “I Am a Little Dreidl (Ikh bin a kleyner dreidl).”

Other Yiddish offerings are Mark Zuckerman’s arrangement of “O, Ir Kleyne Likhtelekh” (“O, You Little Candle”), the lyrics of which were written by poet and lyricist Morris Rosenfeld, and an arrangement by Zuckerman of “Fayer, fayer” (“Fire, Fire”) by Vladimir Heyfetz, about burning the latkes while frying them.

Applebaum’s jazzy “Al Hanism” (“For the Miracles”) is one of three versions of the song on this recording. There is also an arrangement by Elliott Z. Levine that is the traditional, fast-paced version I’ve sung countless times and love, and the expansive, movie soundtrack-sounding arrangement by Joshua Fishbein.

Levine also contributes “Lo v’Chayil” (“Not by Might”), based on text from the Book of Zechariah, which is not a Hanukkah song per se, but, as the liner notes say, “rather the more transcendent spirit that underlies the commemoration of Hanukkah.” Translated from the Hebrew, the verse is: “Not by might nor by power, but by My spirit, saith the Lord of Hosts.”

Other composers/arrangers whose work is featured on this CD are Steve Barnett (“S’vivon” / “Little Dreydl”), Gerald Cohen (“Chanukah Lights”), Daniel Tunkel (four movements of his “Hallel Cantata”), Jonathan Miller (“Biy’mey Mattityahu” / “In the Days of Mattityahu”).

Two bonus tracks are included: an arrangement by Joshua Jacobson of Chaim Parchi’s Hanukkah tune “Aleih Neiri” and Stacy Garrop’s take on the prayer for peace “Lo Yisa Goy”: “Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.”

In the program notes, Miller, who is Chicago a cappella’s artistic director emeritus, talks about the limited number of Hanukkah songs that are appropriate for an ensemble to perform, commenting that “Jewish choral music is a recent phenomenon, begun in earnest only about 200 years ago in Berlin, so there’s a simple quantity issue: we have much less repertoire to peruse than in other choral traditions. Given all of this, we are especially grateful for the composers and arrangers whose persistence and skill have given us the works found here.”

Despite the dearth of Hanukkah choral music, Trotter, the ensemble’s current artistic director, observes that the CD comprises “a sprawling variety of styles.”

“There are at least two reasons for this breadth,” he writes. “On the one hand, we are in debt to the fertile imaginations of our composers, who envisioned so many different sound worlds and so many different ways to clothe these texts. But there is also the nature of Hanukkah itself, which offers so many different modes of personal, social and spiritual practice. Consider just three of these. Hanukkah offers the chance to reflect on the historical significance of the Maccabean revolt, with its consequences echoing through to the present day. It invites quiet contemplation of the candle flames, set aside from any utilitarian purpose. And it provides an opportunity to gather with family and have a really great party with really great food.”

Miracle of Miracles would provide a perfect acoustic background for a Hanukkah gathering. To purchase a CD or buy or stream the music digitally, visit cedillerecords.org/albums/miracle-of-miracles.