The first time I met Gina Dimant and her husband Sasha was in 2000 at the opening of my exhibition Evidence of Truth at the Sidney and Gertrude Zack Gallery. The exhibition was dedicated to all victims of Nazi concentration camps, which included my grandfather, who survived Auschwitz, only to be killed in the Flossenburg-Leitmeritz concentration camp. Years later, when I joined the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada, I met Gina again. She was the president of the association. I also met there Olga Medvedeva-Nathoo, the association’s co-founder.

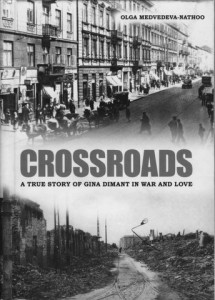

I felt quite honored when Gina asked me to write a review of Medvedeva-Nathoo’s new book, Crossroads: A True Story of Gina Dimant in War and Love (K&O Harbor, 2014). Written originally in Russian, the English edition is translated by Richard J. Reisner and Medvedeva-Nathoo. It was launched on Jan. 11 of this year at the Zack Gallery.

Crossroads is truly an inspired and absorbing account. Born Hinda Wejgsman into a Jewish family in pre-Second World War Warsaw, Gina’s carefree life fell apart when the Nazis invaded Poland. Almost overnight she lost her safe home and, with her parents and sister, had to leave behind extended family, never to see them again.

Crossroads is truly an inspired and absorbing account. Born Hinda Wejgsman into a Jewish family in pre-Second World War Warsaw, Gina’s carefree life fell apart when the Nazis invaded Poland. Almost overnight she lost her safe home and, with her parents and sister, had to leave behind extended family, never to see them again.

Crossroads follows the Wejgsmans family, their extraordinary journey in a cattle car from the eastern border of Nazi-occupied Poland to the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics, and of their fight for survival there. The cold in the car was intolerable, and the Wejgsmans slept on straw, bodies side by side, trying to keep warm. They traveled for more than a month. They were sent to Leninogorsk in northeastern Kazakhstan, near the Altai Mountains, where temperatures dropped to minus 41˚C in winter.

After their arrival, Gina did not go to school because local authorities considered her an adult at 14 and gave her a construction job carrying bricks, four at a time. Gina reflects: “… my main memory from Leninogorsk is not what we ate there, but how terribly hungry we always were. With the feeling of hunger, you couldn’t even fall asleep and, if you fell asleep, then it was with night dreams of food until you woke up with the same daydreams…. In winter evenings when the frost was absolutely intolerable and it was inconceivable even to attempt lying in bed, so as not to freeze to death, we would pace the room in circles, single file.”

The Wejgsman family survived six years in Leninogorsk. Medvedeva-Nathoo points out that it was exactly 72 months, slightly more than 2,000 days.

The postwar return of Gina and her family to Poland necessitated resettling, as Warsaw was in ruins. There was also some serenity, however. In her new town, in Szczecin, Gina’s son from her first marriage, Saul Seweryn, was born. There, she also met her true love, Sasha, and became Gina Dimant.

The Polish 1968 political crisis, known in Poland as the March Events, resulted in the suppression and repression of Polish dissidents and the shameful antisemitic, “anti-Zionist” campaign waged by the Polish Politburo, followed by forced mass emigrations of Polish Jews. Gina remembers: “Poland rejected us unfairly and unjustly. A deep-seated pain lived in us for years…. We were … convinced constantly: there are Poles and there are Poles. Those who were corrupt and added to corruption, and those who sympathized with us … those who gloated over other’s misfortunes and those who were outright angry at our departure.”

Gina, with her husband and son, was displaced again. Looking for a place to settle, they chose Canada because it was a country far away from Europe that accepted new citizens. They arrived here in 1970. Despite their bitter farewell to Poland, their home here was always open to Poles, Jewish and non-Jewish: “A good human being – here was the only essential criterion taken into consideration.”

In Vancouver, in 1999, Gina co-created the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada. In 2013, she was awarded the Gold Officer Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland for strengthening relations between Poles and Jews.

Medvedeva-Nathoo writes: “Tragic Polish-Jewish relations notwithstanding, Poles and Jews lived side by side through the centuries and, regardless of what isolationists like to say, their history cannot be separated. The Dimants would always say: ‘… in the years of war, some Poles, obsessed with hatred, denounced Jews, while others risked their own lives to rescue them at a time when Poland was the only occupied country in which the death penalty was in force for anyone who hid the Jews or in some manner helped Jews.’” In the book, Gina reflects that there are many good and bad examples, pointing with triumph to Irena Sendler, a Pole who saved 2,500 Jewish children.

In Crossroads, Medvedeva-Nathoo has chosen to emphasize the battle of the individual and the will to survive set against the backdrop of three different cultures. It is a steadfast piece of writing that presents the stark facts of Gina’s life, set chronologically, starting with the description of her childhood in prewar Warsaw, followed by their postwar experiences, concluding in 2013.

At times, Medvedeva-Nathoo’s book is translated from Russian to English too literally, not taking into account the cultural context of the language into which she is translating. For example, when describing the usefulness of the newspaper Pravda in the USSR as toilet paper, the author translates it as a “nude-paper,” which makes sense only in Polish or Russian. Readers would also benefit from a map illustrating Gina’s journeys.

Crossroads is an historically accurate chronicle and a meticulously researched story that provokes discussion about the hardships and consequences of war, and the survival of one extraordinary family. It can be purchased from Gina Dimant at 604-733-6386.

Tamara Szymańska is a visual artist and a columnist for the Takie Zycie, the Polish biweekly magazine for Western Canada. She lives in Vancouver with her husband and their dog.