Dr. Rumman Chowdhury, chief executive officer and founder of Parity, gave the keynote address at the Simces & Rabkin Family Dialogue on Human Rights. (photo from rummanchowdhury.com)

Data and social scientist Dr. Rumman Chowdhury provided a wide-ranging analysis on the state of artificial intelligence and the implications it has on human rights in a Nov. 19 talk. The virtual event was organized by the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg and Vancouver’s Zena Simces and Dr. Simon Rabkin for the second annual Simces & Rabkin Family Dialogue on Human Rights.

“We still need human beings thinking even if AI systems – no matter how sophisticated they are – are telling us things and giving us input,” said Chowdhury, who is the chief executive officer and founder of Parity, a company that strives to help businesses maintain high ethical standards in their use of AI.

A common misperception of AI is that it looks like futuristic humanoids or robots, like, for example, the ones in Björk’s 1999 video for her song “All is Full of Love.” But, said Chowdhury, artificial intelligence is instead computer code, algorithms or programming language – and it has limitations.

“Cars do not drive us. We drive cars. We should not look at AI as though we are not part of the discussion,” she said.

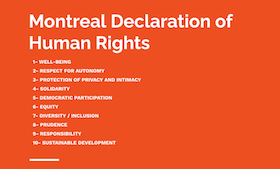

The 2006 Montreal Declaration of Human Rights has served as an important framework in the age of artificial intelligence. The central tenets of that declaration include well-being, respect for autonomy and democratic participation. Around those concepts, Chowdhury addressed human rights in the realms of health, education and privacy.

Pre-existing biases have permeated healthcare AI, she said, citing the example of a complicated algorithm from care provider Optum that prioritized less sick white patients over more sick African-American patients.

“Historically, doctors have ignored or downplayed symptoms in Black patients and given preferential treatment to white patients – this is literally in the data,” explained Chowdhury. “Taking that data and putting it into an algorithm simply trains it to repeat the same actions that are baked into the historical record.”

Other reports have shown that an algorithm used in one region kept Black patients from getting kidney transplants, leading to patient deaths, and that COVID-19 relief allocations based on AI were disproportionately underfunding minority communities.

“All algorithms have bias because there is no perfect way to predict the future. The problem occurs when the biases become systematic, when there is a pattern to them,” she said.

Chowdhury suggested that citizens have the right to know when algorithms are being used, so that the programs can be examined critically and beneficial outcomes to all people can be ensured, with potential harms being identified and corrected responsibly.

With respect to the increased use of technology in education, she asked, “Has AI ‘disrupted’ education or has it simply created a police state?” Here, too, she offered ample evidence of how technology has sometimes gone off course. For instance, she shared a news report from this spring from the United Kingdom, where an algorithm was used by the exam regulator Ofqual to determine the grades of students. For no apparent reason, the AI system downgraded the results of 40% of the students, mostly those in vulnerable economic situations.

Closer to home, a University of British Columbia professor, Ian Linkletter, was sued this year by the tech firm Proctorio for a series of tweets critical of its remote testing software, which the university was using. Linkletter shared his concerns that this kind of technology does not, in his mind, foster a love of learning in the way it monitors students and he called attention to the fact that a private company is collecting and storing data on individuals.

To combat the pernicious aspects of ed tech from bringing damaging consequences to schooling, Chowdhury thinks some fundamental questions should be asked. Namely, what is the purpose of educational technology in terms of the well-being of the student? How are students’ rights protected? How can the need to prevent the possibility that some students may cheat on exams be balanced with the rights of the majority of students?

“We are choosing technology that punishes rather than that which enables and nurtures,” she said.

Next came the issue of privacy, which, Chowdhury asserted, “is fascinating because we are seeing this happen in real-time. Increasingly, we have a blurred line between public and private.”

She distinguished between choices that a member of the public may have as a consumer in submitting personal data to a company like Amazon versus a government organization. While a person can decide not to purchase from a particular company, they cannot necessarily opt out of public services, which also gather personal information and use technology – and this is a “critical distinction.”

Chowdhury showed the audience a series of disturbing news stories from over the past couple of years. In 2018, the New Orleans Police Department, after years of denial, admitted to using AI that sifted through data from social media and criminal history to predict when a person would commit a crime. Another report came from the King’s Cross district of London, which has one of the highest concentrations of facial-recognition cameras of any region in the world outside of China, according to Chowdhury. The preponderance of surveillance technology in our daily lives, she warned, can bring about what has been deemed a “chilling effect,” or a reluctance to engage in legitimate protest or free speech, due to the fear of potential legal repercussions.

Then there are the types of surveillance used in workplaces. “More and more companies are introducing monitoring tech in order to ensure that their employees are not ‘cheating’ on the job,” she said. These technologies can intrude by secretly taking screenshots of a person’s computer while they are at work, and mapping the efficiency of employees through algorithms to determine who might need to be laid off.

“All this is happening at a time of a pandemic, when things are not normal. Instead of being treated as a useful contributor, these technologies make employees seem like they are the enemy,” said Chowdhury.

How do we enable the rights of both white- and blue-collar workers? she asked. How can we protect our right to peaceful and legitimate protest? How can AI be used in the future in a way that allows humans to reach their full potential?

In her closing remarks, Chowdhury asked, “What should AI learn from human rights?” She introduced the term “human centric” – “How can designers, developers and programmers appreciate the role of the human rights narrative in developing AI systems equitably?”

She concluded, “Human rights frameworks are the only ones that place humans first.”

Award-winning technology journalist and author Amber Mac moderated the lecture, which was opened by Angeliki Bogiatji, the interpretive program developer for the museum. Isha Khan, the museum’s new chief executive officer, welcomed viewers, while Simces gave opening remarks and Rabkin closed the broadcast.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.

***

Note: This article has been corrected to reflect that it was technology journalist and author Amber Mac who moderated the lecture.