The Middle East is awash in virulent antisemitism, from the battlefield to the classroom. An Anti-Defamation League global survey of anti-Jewish sentiment last year pinpointed the West Bank, Gaza and Iraq as the world’s most antisemitic lands in the world. More than 90% of those who took the survey in those areas expressed anti-Jewish views.

Some Middle East observers link the blind hatred of Jews in the Middle East to the work of Islamic preachers and Arab leaders who perpetuate the ideology of Nazi Germany. They say that antisemitism is the driving force behind the endless cycle of wars and that nothing that Israel does matters. They maintain that Israel’s enemies will fight until the Jewish state is wiped out and all Jews in the Middle East have been killed.

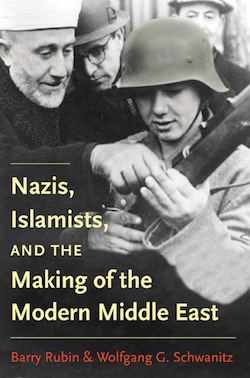

Barry Rubin and Wolfgang G. Schwanitz, in Nazis, Islamists and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Yale University Press), provide ammunition for those who argue that peace is impossible with antisemitic Palestinian and Arab leaders. Rubin, who died before the book was published, was a prolific writer and leading Middle East scholar at the Global Research in International Affairs Centre in Israel. Schwanitz, an accomplished German-American Middle East historian, was a visiting professor at GRIAC at the time of the book’s publication.

Barry Rubin and Wolfgang G. Schwanitz, in Nazis, Islamists and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Yale University Press), provide ammunition for those who argue that peace is impossible with antisemitic Palestinian and Arab leaders. Rubin, who died before the book was published, was a prolific writer and leading Middle East scholar at the Global Research in International Affairs Centre in Israel. Schwanitz, an accomplished German-American Middle East historian, was a visiting professor at GRIAC at the time of the book’s publication.

In their richly researched book, Rubin and Schwanitz document the ancestry of antisemitism in the Middle East over the past century, connecting some of the contemporary Arab and Palestinian leaders to the vitriolic antisemitism of the Nazi collaborator, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husseini.

Backed up by new archival material and previously published research, Rubin and Schwanitz maintain that profound doctrinal hatred for Jews remains the core reason for the Arab-Israel conflict’s enduring and irresolvable nature.

Take a look at Israel’s partners for peace. Heads of state who were once Nazi sympathizers ran regimes that lasted 40 years in Iraq, 50 years in Syria and 60 years in Egypt. An echo of the antisemitism of the 1930s reverberated through speeches of Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, Iraqi’s Saddam Hussein, Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Libya’s Muammar al-Qaddafi and Saudi Arabia’s Osama bin Laden. A Nazi sympathizer educated Yasser Arafat.

However, Rubin and Schwanitz in this book undermine their own credibility by mixing well-documented historical accounts with sweeping pronouncements that seem to be driven by a narrow ideological bias. At times, they sound more like polemicists than historians. They focus on an extreme interpretation of Islam, painting 1.2 billion Muslims with one brush. They ignore history that does not fit easily into their portrait. And their perspective does little to shed light on the contemporary Middle East, where Muslims fight Muslims.

The most provocative assertion in the book is that the grand mufti was responsible for the Nazi gas chambers and crematoria.

Rubin and Schwanitz portray al-Husseini as the most powerful leader of the Arabs and Muslims around the world in mid-century. At the height of his power, he promised Adolf Hitler that the entire Arab people would rally around the Nazi flag and wage a war of terror against Britain and France if Germany would stop all Jewish immigration to Palestine and guarantee independence to countries in the Middle East.

Rubin and Schwanitz maintain that Hitler decided to kill all the Jews only after al-Husseini insisted that they not be deported to Palestine. None of the European countries would accept Jewish refugees. If Palestine would not accept them, the reasoning goes, Hitler had no choice but to build gas chambers.

But their theory has a few holes in it. Historians have never discovered any Nazi plans to transport all the Jews of Eastern Europe and Russia to Palestine. Britain was already restricting immigration. Hitler’s support for al-Husseini’s demand to stop deportations to Palestine was an empty gesture.

Most historians regard al-Husseini as a minor historical figure. Al-Husseini was part of the Nazi war effort and played a role in the death of thousands of Jews. But he was not as powerful or influential in the

Middle East as he is portrayed here. As Rubin and Schwanitz point out, al-Husseini had no plan for actually staging insurrections in support of Nazi Germany. He recruited only 1,000 soldiers outside of Iraq, although he promised 100,000 for the Nazi cause. It is hard to imagine that the Holocaust would not have happened without al-Husseini’s intervention.

Regardless, Rubin and Schwanitz do a good job of placing al-Husseini in the context of the Middle East’s historic ties to Germany. They begin the tale with Max von Oppenheim, an advisor to Kaiser Wilhelm II in the early 1890s, who urged the German ruler to use Islam to inspire a Muslim revolt in the colonies of Germany’s enemies. At that time, Britain, France and Russia controlled the Middle East, India and North Africa. Zionism was not relevant.

The kaiser made a formal pact in 1898 with the Ottoman Empire’s sultan, Abdul Hamid II. Germany anticipated the alliance would lead to an Islamic jihad throughout Muslim lands, but the righteous call to jihad had little impact. Muslims, Turks and Arabs saw themselves as divided by religion, ethnicity, regional interest and self-interest. They paid little attention in their daily lives to the sultan’s belligerent proclamations.

During the First World War, von Oppenheim ran Germany’s covert war in the Middle East, reinvigorating the policy of Islamic jihad. Germany pushed Sultan Mehmed V to trigger a pan-Islamic revolt, as well as attack Russia’s Black Sea ports, and established activist groups in Arab communities dedicated to spread jihad in Russia-ruled Caucasus and in Arab-populated lands. However, once again, the pan-Islamic revolts never materialized. Tribal leaders took the money from Germany and did nothing.

By the late 1930s, the dynamics had reversed. Al-Husseini sought out the support of Nazi Germany. Hitler was initially cool to an alliance, believing the dark-skinned people of the Middle East were inferior to his blond-haired, blue-eyed Aryan nation, but he soon realized the Nazis and Muslims confronted common enemies – Britain, France and the Jews.

A strident antisemite who had been fighting Zionism since 1914, al-Husseini claimed the mantle of leader of transnational Islamism after Turkey, in 1924, abolished the Islamic Caliphate. He solidified his position within the Arab and Muslim communities through violence and murder.

Under his leadership, militancy became mainstream and moderation was regarded as treason. He turned Palestine into the defining issue of the Middle East. Anyone who did not support him or his views was a Zionist and imperial stooge. In the 1930s, he attracted attention for making passionate nationalist speeches in Jerusalem while crowds chanted “Death to Zionism,” rioted and killed Jews. His work clearly set the stage for Arab and Muslim leaders who followed his lead.

Meanwhile, in Germany between the wars, militant Islamists, backed by the disciples of von Oppenheim, solidified their control over mosques in Berlin and elsewhere, espousing an ideology that Rubin and Schwanitz say can be heard today from the pulpits. They cultivated relations with the leadership of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, Iraq’s Ba’ath Party and radical factions in Syria and Palestine. By the time the Nazis looked to the Middle East, they found a ready-made network of radical antisemitic Islamists from Morocco to India, led by al-Husseini, with similar ideology, worldviews and interests. But the Islamic jihad failed once again to materialize.

Nazi ideology collapsed in 1945. However, a radical Arab nationalism, accompanied by a form of al-Husseini Islamism steeped in hatred of the Jews, flourished after the war. Little has changed despite the passage of decades, events and generations. Rubin and Schwanitz say al-Husseini’s legacy can been seen in the words and actions of Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, Muslim Brotherhood and al-Qaeda. For them, as for the Nazis and al-Husseini, Jews are the villains of all history, the eternal enemy without whose extinction a proper world would be impossible.

Rubin and Schwanitz say the Arabic-speaking world’s historical connection with Nazi Germany was not solely responsible for the terrorism, conflict with Israel and anti-Jewish hatreds. However, they say, the historical relationships, along with the ideas and motives prompting it, help explain what has happened over the past 70 years. The forces that forged the partnership between al-Husseini and Hitler returned to help shape the course of Middle East history ever since. And it was not just the Nazi doctrine. In many cases, the individuals responsible for the Middle East’s post-1945 course had direct links to the Nazi era, they say.

“Comprehending this fact is the starting point for understanding modern Middle East history, its turbulence, tragedies and its many differences from other parts of the world,” Rubin and Schwanitz say.

Yes, they make a fascinating case for a starting point in trying to make sense of relations between Germany and the Middle East. But in this book they do not examine the record of contemporary Arab and Muslim leaders in much detail. They leave out other influences and other leading players that contributed to the making of the Middle East. Also, Rubin and Schwanitz seem to ignore that the antisemitism of the radical Islamists preceded their embrace of Nazism.

Rubin and Schwanitz have illuminated one diabolical aspect of a complex state of affairs – but much more remains to be said for a full understanding of the modern Middle East.

Robert Matas, a Vancouver-based writer, is a former journalist with the Globe and Mail. This review was originally published on the Isaac Waldman Jewish Public Library website and is reprinted here with permission. To reserve this book or any other, call 604-257-5181 or email [email protected]. To view the catalogue, visit jccgv.com and click on Isaac Waldman library.